By Patrick Kwasi Brobbey, Research Project Manager, Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), Transparency International Defence & Security

I still recall the soft murmur of anticipation in the lecture hall at the London School of Economics during the Black History Month event I co-chaired in October 2023. The discussion that evening centred on the sobering truth that colonialism did not end with independence, as its aftershocks still reverberate through our institutions, shaping who speaks, who is heard, and who is written out. Those words linger with me. Now, as the Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) Research Project Manager, it strikes me how similar hierarchies persist not only through geographic conquest, but also through data, research, and policy frameworks that too often exclude the very voices they claim to represent. As we mark Black History Month in the UK and celebrate resilience, inclusion, and the ongoing struggle for justice, I find myself reflecting on the lessons my work in defence governance holds for confronting these subtle, enduring imbalances of power in knowledge creation.

Introducing the GDI and the Decolonial Perspective

Corruption in defence establishments threatens peace and security by wasting public resources and undermining military capability and the public’s confidence in defence institutions. Yet, owing to the fact that ‘defence exceptionalism’ enables significant secrecy around the workings of defence institutions, it is difficult to monitor and understand defence institutions’ activities to pre-empt and resolve corruption risks. This is where the GDI comes in. It is Transparency International Defence & Security’s flagship global assessment of institutional resilience to corruption in the defence and security sector. It ordinarily evaluates 212 indicators across five risk areas, namely political, financial, personnel, operations, and procurement. Alongside these indicators, the 2025 GDI is piloting two sets of additional indicators, one on the gender dimension of defence sector corruption risks and the other, corruption risks in the protection of civilians and civilian harm mitigation efforts.

Since its inception in 2013 (as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index), the GDI has grown into a respected evidence-based tool used by regional and international organisations, governments, civil society, and the media. Now in its fourth iteration, the 2025 GDI data collection presently covers the sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, and Central and Eastern Europe waves. We are close to completing the sub-Saharan Africa wave comprising 17 countries, including Liberia, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, Madagascar, Uganda, and Burundi. Passed through a decolonial lens, my experiences from this wave mostly inform my reflections here.

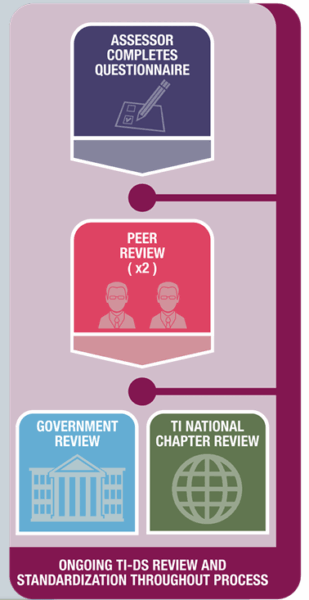

Decolonial scholars remind us that colonialism was not coterminous with independence, since it has persisted through the domination of knowledge, representation, and resources. In this sense, like all large-scale research projects with global scope, the GDI operates within complex asymmetries, particularly disparities in access, visibility, and epistemic authority between the Global North and Global South. To create an index that truly reflects global realities, the GDI not only collects data or produces knowledge globally but does so equitably. This and its benefits can be seen in the GDI research process, whose activities are illustrated in the diagram below.

Source: GDI Methods Paper (2020)

The GDI Country Assessment Process: Building Inclusion into Research

Country Assessment Onset: Transparency International Chapter Consultation

The GDI is primarily produced for Transparency International national chapters – locally established, independent organisations in the Transparency International movement whose purpose is to fight corruption within their respective countries. As such, the sub-Saharan Africa wave began with a March 2024 consultation webinar with Transparency International national chapters in participating countries (e.g., TI Ghana, TI Mozambique, and TI Madagascar) and relevant Transparency International regional advisors.

During this interactive session, we sought their advice on conducting the research in their national and local contexts, including navigating political sensitivities, barriers to access, and potential opportunities and risks to researchers and other stakeholders.

This is more than procedural courtesy. It is epistemic humility. Through the discussions, the chapters and advisors confirm, complement, and challenge the global standards underlying the GDI framework, the GDI research design, its implementation in their countries, and the lenses through which GDI data is interpreted. In decolonial terms, this represents a small but crucial shift from extracting knowledge to co-creating it. As Peace Direct puts it, decolonising research means shifting power to allow for those closest to issues to contribute to the definition of questions and solutions.

During the Assessment: Local Expertise at the Core

Locally based country assessors, often PhD-level researchers with proven expertise on their national defence and security sectors, conduct the GDI country assessments. These experts ground their analysis in the intricacies of domestic policy debates that some external consultants are likely to miss.

Working with them – all of whom have a track record of undertaking field research, publishing in credible international and local outlets, and working with reputable local and international organisations – enables TI-DS to reject the antiquated hierarchy that equates credibility with only proximity to the West. We recognise that local expertise is global expertise, in that experts embedded within systems tend to possess some of the deepest contextual understanding. By prioritising national researchers, the GDI helps to affirm this, echoing the renowned Kenyan author and academic Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o‘s powerful advocacy for hinging the healing of the colonised mind on its realisation that it is the generator of its own knowledge.

Peer Review: Collaboration, Not Correction

Once an assessment is complete, TI-DS coordinates a rigorous peer review. Each draft country assessment is evaluated by two additional country experts. The purpose of this stage is not to ‘correct’ local voices with external ones, but to strengthen the work further by establishing dialogue between different epistemic communities. This exchange deepens the data’s accuracy, illustrating how diversity of perspective enhances research credibility.

Validation: Listening to Governments and Civil Society

The process concludes with consultations with TI national chapters and relevant governments, typically ministries of defence. We invite TI national chapters and ministries of defence to provide evidence-based feedback. For the 2025 GDI sub-Saharan Africa wave, more than half of the national chapters accepted this invitation, notwithstanding that many chapters do not have a defence sector mandate, interest, and/or expertise. Ministries of defence that honoured this invitation include those of Nigeria and Liberia. Rooted in mutual respect, this inclusive final stage not only ensures fairness but also helps foster data quality and the national and local ownership of the findings. This collaborative effort can advance positive change in the defence and security sector’s governance.

Why Decolonising Research Matters

From decolonial theories, we know that knowledge and its production are never neutral. Rather, they reflect the power structures that control them. When research in global policy domains reproduces Eurocentric frameworks by examining phenomena solely through Western epistemologies without national/local considerations, it risks misrepresenting the realities of the societies it assesses. Furthermore, if data collection and analysis are blind to racialised or cultural dynamics of power, the evidence base itself becomes incomplete. This imbalance, which perpetuates injustice and distorts reality, in turn, undermines both the credibility and the uptake of findings among local actors.

The GDI’s iterative consultation model, entailing engagement of national chapters, local experts, and governments, is one way of disrupting this imbalance. It allows for plural epistemologies to coexist within a single global framework. To decolonise, therefore, is not to reject universal standards, but to recognise that universality can only emerge from dialogue among equals, not from prescription by the powerful.

Towards a More Just Knowledge Order

Black History Month reminds us that history is not only what happened but also who gets to tell it. The same is true of data. For too long, the production of knowledge in global governance has mirrored colonial hierarchies: data collected ‘there’ but validated ‘here’. Local expertise is discounted in favour of distant credentials. As researchers and policymakers, we have an obligation to disrupt this pattern.

Building indices like the GDI through a decolonial perspective is not an act of charity or political correctness, but an act of rigour. It makes our findings more representative, our analyses more credible, and our recommendations more actionable. As the globally celebrated Nigerian novelist and essayist Chinua Achebe once asserted, ‘Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.’ The GDI, at its best, seeks to amplify the lions, i.e., the local voices whose perspectives are essential to understanding and reforming defence integrity worldwide.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Map

The colonial cartographers of old believed that to control a space, one must define it. Today, the challenge for global research is to map without domination and to measure without silencing. The process of creating the GDI teaches us that recalibrating uneven racial power dynamics is not peripheral to research quality. Instead, it is its foundation. When those who live the realities of governance and security are full partners in collecting and interpreting data, the result is not only more just but also more accurate and credible. As we mark Black History Month, may we remember that the fight against corruption and the fight against epistemic injustice are, ultimately, the same fight.