Author: ewegener

At the side of the 59th session of the Human Rights Council in Geneva, TI-DS and partners co-organised a panel discussion to discuss solutions to the vicious cycle of corruption, human rights violations, and insecurity. Senior Policy & Campaigns Officer Emily Wegener shares takeaways and reflections from the event.

Security and law enforcement agencies are often the first point of contact between citizens and the state. When they abuse their power, the impact on trust and state legitimacy cuts deep. Corruption also diverts resources from the fulfilment of human rights and peacebuilding. This makes corruption both a human rights issue and a threat to international peace and security – yet it is not treated as such: anti-corruption measures are still often viewed more as a technical fix, rather than as a necessity to ensure the enjoyment of human rights and prevent armed conflict.

To mark the launch of ‘Sabotaging Peace: Corruption as a Threat to International Peace and Security’ last week, TI-DS co-convened a panel discussion with DCAF and the UN Human Rights Office (UN OHCHR) on ‘Corruption, Human Rights and Security: Strengthening Prevention Through Accountability’ in Geneva. At this year’s 59th session, the Human Rights Council (HRC) will adopt a renewed resolution on ‘The negative impact of corruption on the enjoyment of human rights’ — a timely backdrop for a discussion examining how corruption in defence, security and law enforcement undermines the protection and enjoyment of human rights.

Sharing headlines from ‘Sabotaging Peace’, Dr Francesca Grandi, Head of Programme at TI-DS, called for the need for a paradigm shift in peacebuilding, peacekeeping, security sector reform (SSR) and disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) processes. Current approaches prioritise stabilisation over reform and thus fail to introduce anti-corruption measures from the onset. Corrupt networks, however, don’t wait: they are quick to adapt and entrench themselves in post-conflict political structures. By the time a situation is considered stable enough to integrate transparency and accountability instruments, corruption has often already become endemic.

Upasana Garoo, Senior Advisor at DCAF, shared findings from the new report on Corruption Controls and Integrity-Building in Law Enforcement. She highlighted how corruption in law enforcement is systemic and strategic, and not just a consequence but also a driver of weak governance. Effective solutions should be grounded in an understanding of the political economy, aim at changing incentive structures, balance practicality with political realism, and be mutually reinforcing.

María José Veramendi Villa, Human Rights and Anti-Corruption Officer at the UN OHCHR, shared insights from a report published in March on the ‘Impact of arms transfers on human rights’, which highlights how the lack of good governance in the defence sector contributes to illicit arms transfers and diversion. The lack of transparency in the sector, close industry-government ties, conflicts of interest, as well as complex, transnational procurement lines exacerbate corruption risks in arms transfers. To mitigate these risks, actors should adopt a human rights-based approach to anti-corruption, which puts the victims at the centre and highlights that corruption negatively impacts a State’s ability to fulfil its human rights obligations.

Insights from evidence and practice on proven solutions

The problem is complex and widespread, but there are proven solutions. Key panel recommendations included:

- Adopt a human-rights-based and conflict-sensitive approach to anti-corruption: Design anti-corruption initiatives with the aim to prevent human rights violations and conflict, putting victims of corruption at the centre; and foster closer collaboration between national, regional, and international human rights, peacebuilding, security sector reform, and anti-corruption bodies, as well as coherence between policies and strategies addressing these issues.

- Ensure complementarity and a systems-based approach: Ground peacebuilding, SSR, and anti-corruption initiatives on political economy analyses that examine the underlying socio-economic and power systems, as well as the incentive structures driving corruption at different levels. Use PEA to identify gaps across the entire system and put in place measures that are mutually reinforcing.

- Build coalitions across the whole of society: Successful interventions managed to build ‘coalitions of the willing’ across media, civil society, government, donors and the private sector, to create the right structure of incentives and identify multiple entry points for change.

- Emphasize human rights due diligence in arms transfers: Encourage companies in the defence and security sectors to adopt human rights policies that included a due diligence process.

- Attach targeted conditionality to military assistance: Make the provision of military assistance conditional on transparency, accountability and anti-corruption measures (e.g. external audits, open contracting regulations, public access to information).

- Transform social norms: Examine the cultural and social norms that defence, security and law enforcement forces are operating in, alongside institutional weaknesses. Where corruption is seen as necessary, and is generally socially accepted, pair technical solutions with longer-term, transformative measures aimed at shifting social norms.

In fragile contexts, corruption is the glue holding together violent systems that have the power to block meaningful attempts at building peace and protecting human rights. Anti-corruption is a powerful tool to prevent and mitigate violence, conflict and human rights violations – if we put anti-corruption and conflict-sensitivity at the core of these interventions/approaches.

At a time of mounting geopolitical tensions and growing instability, governments around the world are spending record sums on defence and security, writes Yi Kang Choo, our International Programmes Officer.

Recent data highlights this move towards increased militarisation. PwC’s 2024 Annual Industry Performance and Outlook reports a 7% increase in overall revenues among the top 11 defence companies in 2023. Leading contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and BAE Systems are grappling with record-high defence order backlogs, with an 11% increase in value to $747 billion. Meanwhile, an analysis by Vertical Research Partners for the Financial Times forecasts that by 2026, the leading 15 defence contractors will nearly double their combined free cash flow to $52 billion compared to 2021.

These figures demonstrate a sector on an upward trajectory, buoyed by heightened demand and increased defence budgets largely due to escalating geopolitical tensions and conflicts globally. Reinforcing this trend, the 2024 Global Peace Index highlights an increase of, while global military expenditure surged to an unprecedented $2.443 trillion in 2023, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

In this blog, we will delve into the importance of strong governance standards for defence companies, and outline the role companies, boards, and investors (who are susceptible to the risks of the supply side of corruption and bribery) in fostering a culture of integrity, accountability and transparency within the sector.

At Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), we have long raised concerns about the risks associated with surging military spending. In our Trojan Horse Tactics report, we show that increased defence spending without appropriate oversight often correlates with rising corruption risks. In countries that are not equipped with the requisite institutional safeguards, an influx of funds is most likely to benefit corrupt actors across defence establishments, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that prioritises private gain over peace and security outcomes. Nevertheless, robust governance standards are not only essential for officials and government (the demand side of corruption), but are equally vital for defence companies and contractors on the supply side, particularly as the stakes continue to rise.

The Profit Boom: A Double-Edged Sword

For many in the defence sector, the current boom in profits is a cause for celebration. However, the rapid influx of funds brings increased risks to the industry, too. Despite widespread acknowledgment within the sector that corruption is harmful to business, companies continue to face challenges in effectively implementing preventative measures.

Corruption in the defence industry is also persistent. The combination of complex procurement processes and high value contracts creates a fertile ground for opaque practices, further exposing governance vulnerabilities and inefficiencies within companies. Notably, some of the world’s largest defence companies have faced significant allegations of corruption in recent years:

In 2014, a UK subsidiary of AgustaWestland S.p.A (now under Leonardo) was fined €300,000 – while its parent company AgustaWestland was fined €80,000 – to settle an Italian investigation into allegations of bribery relating to the sale of 12 helicopters to the Indian military. In addition, the court ordered the confiscation of €7.5 million in company profits.

In January 2017, Rolls Royce entered into record-breaking settlements in the US, UK, and Brazil to resolve numerous bribery and corruption allegations involving its . The UK and US settlements involved Deferred Prosecution Agreements worth £497 million and $170 million respectively, while a leniency agreement with Brazilian prosecutors amounted to almost £21 million.

In 2021, UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) secured a corporate conviction against GPT Special Project Management, a former subsidiary of Airbus. GPT pleaded guilty after a near decade-long investigation to a single count of corruption and was ordered to pay over £30m in confiscation, fines, and costs.

In November 2024, a fraud investigation was launched into suspected bribery and corruption at Thales in relation to four of its entities by the Parquet National Financier in France and the UK’s SFO. Thales denied the allegations and said that it complied with all national and international regulations. The investigation is still ongoing. Likewise, earlier in June 2024, triggered by two separate investigations of suspected corruption, money laundering, and criminal conspiracy linked to Thales’ arms sales abroad, police in France, Spain, and the Netherlands also conducted searches in its respective country offices. A spokesperson for Thales confirmed to Reuters that searches had taken place but gave no further details beyond saying that the company was cooperating with authorities.

As seen in the examples above, corruption can also be costly. When allegations are levelled against a company, lengthy investigations divert resources and cause reputational damage. Convictions or settlements may result in large fines, claims for damages and ultimately exclusion from key markets.

And the costs to companies are likely to rise. Increasing shareholder activism and Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG)-driven investment strategies meant that investors and stakeholders are scrutinising companies’ ethical practices more than ever. Defence firms that fail to prioritise anti-corruption and transparency risk alienating their stakeholders and jeopardising long-term growth.

The Shadow of Lobbying and Undue Influence

With defence companies forecast to have more cash available in the coming years, spending on share buybacks, increased dividends, and expansion will not be their only focus – it’s also vital not to ignore the risks of companies exerting undue influence on government defence policy.

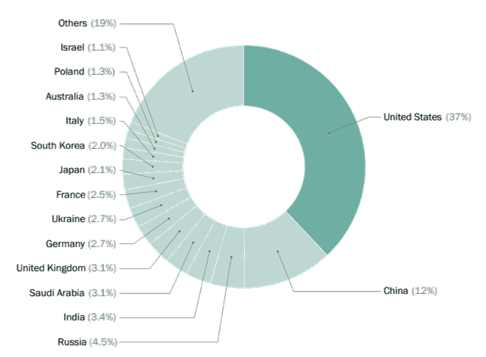

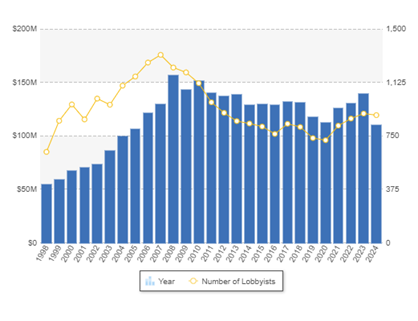

According to Open Secrets, in 2024, up to $110 Million was spent by defence industries to lobby the US government (including political candidates and committees) in securing government defence contracts, earmarks, and influencing the defence budget to make certain contracts more likely. Amongst the 896 lobbyists, more than half of them (63.28%) consist of former government employees – a stark example of the ‘revolving door’ between the public and private sector which is especially pervasive situation in the global defence industry where significant conflicts of interest may occur if not appropriately regulated.

Whilst traditional lobbying activity with policy makers and institutions to exchange ideas and influence certain policies forms an essential part of the democratic process, the amount of money defence companies spend on lobbying activities, combined with a lack of transparency, may mutate lobbying processes into privileged access. It can also create opportunities to wield considerable influence over politicians and officials responsible for shaping public policy, heightening the risk of policy decisions being disproportionately skewed in favour of individual companies rather than serving the broader public interest. Moreover, for governments and industry regulators, this underscores the need for stringent oversight and transparency measures to ensure that lobbying activities do not undermine democratic processes or market fairness.

The Time to Act is Now: The Role of Companies, Boards, and Investors

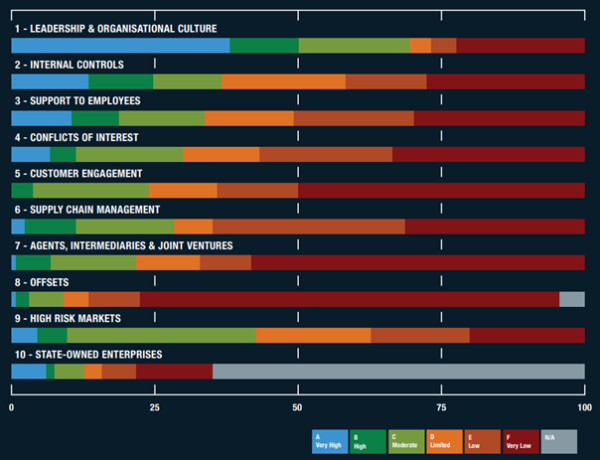

Despite these challenges, the compliance and transparency efforts of companies should not be understated. According to the Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) 2020, most of the world’s largest defence companies have established publicly available ethics and anti-corruption programmes, with robust policies and procedures in place for employees to follow. Industry associations now also have dedicated ethics committees, and many companies participate in platforms such as the International Forum on Business Ethics (IFBEC) and the Defence Industry Initiative for Business Ethical Conduct (DII) which enabled ethics and compliance staff within major companies to access more resources and to receive more senior recognition for their work. However, there is still more work to do. Many major defence companies still do not publish or show no evidence of a clear procedure to deal with the highest corruption risk areas, such as their supply chains, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures, and offsets.

Companies have a crucial role to play to in building and strengthening policies, practices, and a culture of integrity, accountability and transparency within the defence sector worldwide. We call on companies to put anti-corruption and transparency at the very core of their corporate agenda, alongside promoting discussions on how to raise governance standards across the organisational, national, and regional forums in which they are part of. Companies are also encouraged to engage with civil society organisations and anti-corruption experts to exchange learnings, foster accountability, and encourage further employee engagement in the mitigation of corruption risks across the business.

Directors of companies should exercise their fiduciary duties effectively by holding executives accountable when proactive procedures and steps are not being taken to detect, prevent, and address corruption in the highest risk areas. They could also encourage the meaningful disclosure of the company’s corporate political engagement, especially any political and lobbying contributions, to uphold the reputation and long-term stability of the company as it poses a particularly high-risk in the defence sector.

Finally, investors in defence companies could emphasise anti-corruption transparency as an essential cross-cutting issue embedded within ESG initiatives, and to urge the companies in which they hold shares to increase meaningful disclosures of their ethics and anti-corruption programmes. Investors wield significant influence in shaping corporate behaviour, and by advocating for these changes, investors can drive long-term value creation while promoting ethical business practices.

The defence industry is at a critical juncture. As military spending and corporate revenues soar, the stakes for maintaining ethical governance have never been higher. Robust governance standards are essential – not only to mitigate corruption risks but also to uphold the sector’s integrity in an increasingly interconnected and scrutinised global landscape. By taking decisive action and establishing clearly defined, targeted processes, defence companies, boards, and investors can ensure that the industry remains resilient, competitive – and most importantly – aligned with the principles of transparency and accountability.