Show Index: dci

At a time of mounting geopolitical tensions and growing instability, governments around the world are spending record sums on defence and security, writes Yi Kang Choo, our International Programmes Officer.

Recent data highlights this move towards increased militarisation. PwC’s 2024 Annual Industry Performance and Outlook reports a 7% increase in overall revenues among the top 11 defence companies in 2023. Leading contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and BAE Systems are grappling with record-high defence order backlogs, with an 11% increase in value to $747 billion. Meanwhile, an analysis by Vertical Research Partners for the Financial Times forecasts that by 2026, the leading 15 defence contractors will nearly double their combined free cash flow to $52 billion compared to 2021.

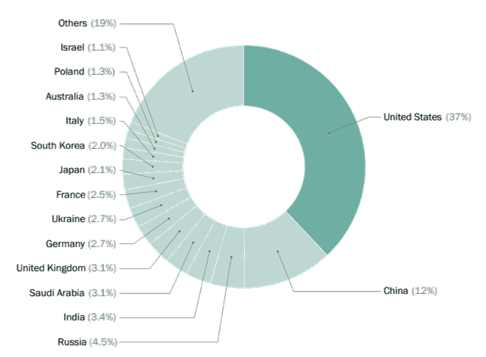

These figures demonstrate a sector on an upward trajectory, buoyed by heightened demand and increased defence budgets largely due to escalating geopolitical tensions and conflicts globally. Reinforcing this trend, the 2024 Global Peace Index highlights an increase of, while global military expenditure surged to an unprecedented $2.443 trillion in 2023, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

In this blog, we will delve into the importance of strong governance standards for defence companies, and outline the role companies, boards, and investors (who are susceptible to the risks of the supply side of corruption and bribery) in fostering a culture of integrity, accountability and transparency within the sector.

At Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), we have long raised concerns about the risks associated with surging military spending. In our Trojan Horse Tactics report, we show that increased defence spending without appropriate oversight often correlates with rising corruption risks. In countries that are not equipped with the requisite institutional safeguards, an influx of funds is most likely to benefit corrupt actors across defence establishments, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that prioritises private gain over peace and security outcomes. Nevertheless, robust governance standards are not only essential for officials and government (the demand side of corruption), but are equally vital for defence companies and contractors on the supply side, particularly as the stakes continue to rise.

The Profit Boom: A Double-Edged Sword

For many in the defence sector, the current boom in profits is a cause for celebration. However, the rapid influx of funds brings increased risks to the industry, too. Despite widespread acknowledgment within the sector that corruption is harmful to business, companies continue to face challenges in effectively implementing preventative measures.

Corruption in the defence industry is also persistent. The combination of complex procurement processes and high value contracts creates a fertile ground for opaque practices, further exposing governance vulnerabilities and inefficiencies within companies. Notably, some of the world’s largest defence companies have faced significant allegations of corruption in recent years:

In 2014, a UK subsidiary of AgustaWestland S.p.A (now under Leonardo) was fined €300,000 – while its parent company AgustaWestland was fined €80,000 – to settle an Italian investigation into allegations of bribery relating to the sale of 12 helicopters to the Indian military. In addition, the court ordered the confiscation of €7.5 million in company profits.

In January 2017, Rolls Royce entered into record-breaking settlements in the US, UK, and Brazil to resolve numerous bribery and corruption allegations involving its . The UK and US settlements involved Deferred Prosecution Agreements worth £497 million and $170 million respectively, while a leniency agreement with Brazilian prosecutors amounted to almost £21 million.

In 2021, UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) secured a corporate conviction against GPT Special Project Management, a former subsidiary of Airbus. GPT pleaded guilty after a near decade-long investigation to a single count of corruption and was ordered to pay over £30m in confiscation, fines, and costs.

In November 2024, a fraud investigation was launched into suspected bribery and corruption at Thales in relation to four of its entities by the Parquet National Financier in France and the UK’s SFO. Thales denied the allegations and said that it complied with all national and international regulations. The investigation is still ongoing. Likewise, earlier in June 2024, triggered by two separate investigations of suspected corruption, money laundering, and criminal conspiracy linked to Thales’ arms sales abroad, police in France, Spain, and the Netherlands also conducted searches in its respective country offices. A spokesperson for Thales confirmed to Reuters that searches had taken place but gave no further details beyond saying that the company was cooperating with authorities.

As seen in the examples above, corruption can also be costly. When allegations are levelled against a company, lengthy investigations divert resources and cause reputational damage. Convictions or settlements may result in large fines, claims for damages and ultimately exclusion from key markets.

And the costs to companies are likely to rise. Increasing shareholder activism and Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG)-driven investment strategies meant that investors and stakeholders are scrutinising companies’ ethical practices more than ever. Defence firms that fail to prioritise anti-corruption and transparency risk alienating their stakeholders and jeopardising long-term growth.

The Shadow of Lobbying and Undue Influence

With defence companies forecast to have more cash available in the coming years, spending on share buybacks, increased dividends, and expansion will not be their only focus – it’s also vital not to ignore the risks of companies exerting undue influence on government defence policy.

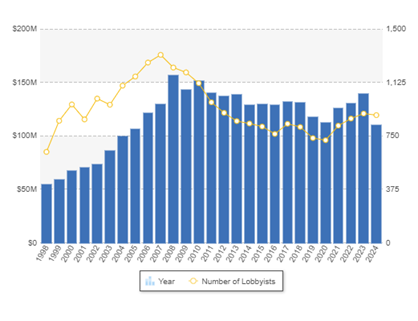

According to Open Secrets, in 2024, up to $110 Million was spent by defence industries to lobby the US government (including political candidates and committees) in securing government defence contracts, earmarks, and influencing the defence budget to make certain contracts more likely. Amongst the 896 lobbyists, more than half of them (63.28%) consist of former government employees – a stark example of the ‘revolving door’ between the public and private sector which is especially pervasive situation in the global defence industry where significant conflicts of interest may occur if not appropriately regulated.

Whilst traditional lobbying activity with policy makers and institutions to exchange ideas and influence certain policies forms an essential part of the democratic process, the amount of money defence companies spend on lobbying activities, combined with a lack of transparency, may mutate lobbying processes into privileged access. It can also create opportunities to wield considerable influence over politicians and officials responsible for shaping public policy, heightening the risk of policy decisions being disproportionately skewed in favour of individual companies rather than serving the broader public interest. Moreover, for governments and industry regulators, this underscores the need for stringent oversight and transparency measures to ensure that lobbying activities do not undermine democratic processes or market fairness.

The Time to Act is Now: The Role of Companies, Boards, and Investors

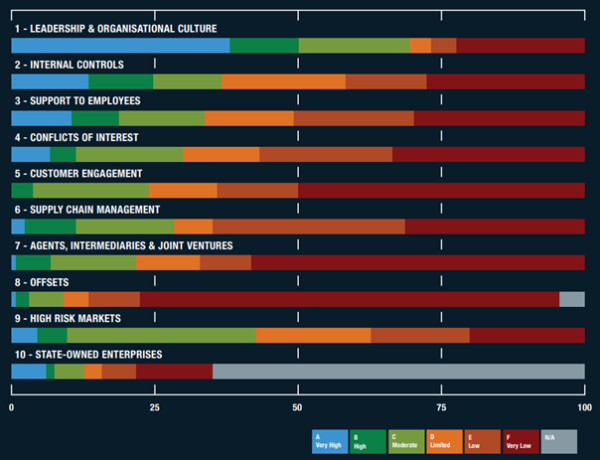

Despite these challenges, the compliance and transparency efforts of companies should not be understated. According to the Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) 2020, most of the world’s largest defence companies have established publicly available ethics and anti-corruption programmes, with robust policies and procedures in place for employees to follow. Industry associations now also have dedicated ethics committees, and many companies participate in platforms such as the International Forum on Business Ethics (IFBEC) and the Defence Industry Initiative for Business Ethical Conduct (DII) which enabled ethics and compliance staff within major companies to access more resources and to receive more senior recognition for their work. However, there is still more work to do. Many major defence companies still do not publish or show no evidence of a clear procedure to deal with the highest corruption risk areas, such as their supply chains, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures, and offsets.

Companies have a crucial role to play to in building and strengthening policies, practices, and a culture of integrity, accountability and transparency within the defence sector worldwide. We call on companies to put anti-corruption and transparency at the very core of their corporate agenda, alongside promoting discussions on how to raise governance standards across the organisational, national, and regional forums in which they are part of. Companies are also encouraged to engage with civil society organisations and anti-corruption experts to exchange learnings, foster accountability, and encourage further employee engagement in the mitigation of corruption risks across the business.

Directors of companies should exercise their fiduciary duties effectively by holding executives accountable when proactive procedures and steps are not being taken to detect, prevent, and address corruption in the highest risk areas. They could also encourage the meaningful disclosure of the company’s corporate political engagement, especially any political and lobbying contributions, to uphold the reputation and long-term stability of the company as it poses a particularly high-risk in the defence sector.

Finally, investors in defence companies could emphasise anti-corruption transparency as an essential cross-cutting issue embedded within ESG initiatives, and to urge the companies in which they hold shares to increase meaningful disclosures of their ethics and anti-corruption programmes. Investors wield significant influence in shaping corporate behaviour, and by advocating for these changes, investors can drive long-term value creation while promoting ethical business practices.

The defence industry is at a critical juncture. As military spending and corporate revenues soar, the stakes for maintaining ethical governance have never been higher. Robust governance standards are essential – not only to mitigate corruption risks but also to uphold the sector’s integrity in an increasingly interconnected and scrutinised global landscape. By taking decisive action and establishing clearly defined, targeted processes, defence companies, boards, and investors can ensure that the industry remains resilient, competitive – and most importantly – aligned with the principles of transparency and accountability.

The scandals that shook the world into action in 2001 to prevent the illicit trafficking of small arms and light weapons (SALW) were often fueled by corruption. Arms brokers bribing government officials to create fraudulent export or import documentation played key roles in these schemes to violate UN arms embargoes.

In other cases, military or police personnel illicitly sold state weapons to insurgent or criminal groups for personal profit.

Several states are increasingly implementing new policies and approaches to better assess and mitigate corruption risks in arms

transfers and stockpile management. These laudable approaches, however, are still in their infant stages. There is also a lack of international coordination and cooperation on the ways in which corruption fuels arms diversion. It’s time for states to elevate their efforts to assess and mitigate corruption’s role in arms diversion by strengthening national and international action and cooperation.

The rise in global insecurity is pushing many US security partner countries to reignite or revise a familiar but risky approach to expanding national defence industrial capabilities. Sometimes referred to as ‘defence offsets’ or ‘industrial participation’, this approach requires foreign defence companies to invest in the local economies of countries as a condition for the purchase of major weapons systems. Defence offsets can benefit local defence industries, but they also contain many aspects that make them particularly vulnerable to corruption. US defence companies are rapidly responding to these partner demands with increasing US government support and within an incredibly lax US regulatory environment.

December 5, 2023 – Four of the world’s 10 biggest arms producers listed in new research from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) show a concerning lack of commitment to anti-corruption, Transparency International Defence & Security said today.

SIPRI’s 2022 Arms Industry Database lists the top 100 arms-producing and military services companies. Four of the top 10 score either an E or F Transparency International’s Defence Companies Index (DCI), which assesses and ranks major global defence companies based on their commitment to anti-corruption and transparency.

In the top four, SIPRI’s data shows General Dynamics (US), NORINCO and AVIC (China), and Rostec (Russia), collectively responsible for $876 billion in global arms trade last year. All scored poorly in the DCI, indicating a minimal or extremely poor commitment to anti-corruption.

The problem extends beyond these firms, with dozens of other companies in the top 100 assessed by the DCI to show poor or non-existent commitment to anti-corruption.

This is alarming given SIPRI’s data on the increasing demand for arms and military services globally. Corruption in the arms trade can have devastating impacts on people’s lives, leading to heightened conflict and violence, undermining governance and the rule of law, diverting resources from essential public services, and eroding trust in institutions.

Josie Stewart, Programme Director at Transparency International Defence & Security, said:

“The latest SIPRI report, when combined with our previous research on arms producers’ commitment to anti-corruption, paints a troubling picture. Far too many of the world’s biggest arms producers are falling short in addressing corruption risks.

“This should urgently motivate governments and the international community to prioritise addressing these issues in the defence and security sectors.

“As demand for arms and military services grows, it’s crucial to ensure that anti-corruption standards remain a forefront consideration, not secondary to trade, foreign, and defence policy objectives. The cost of neglecting integrity and transparency in these sectors is too great to ignore.”

Notes to editors:

Transparency International is a global movement that combats corruption and promotes transparency, accountability, and integrity in government, politics, and business worldwide.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is one of Transparency International’s global programmes and is committed to tackling corruption in the global defence and security sector.

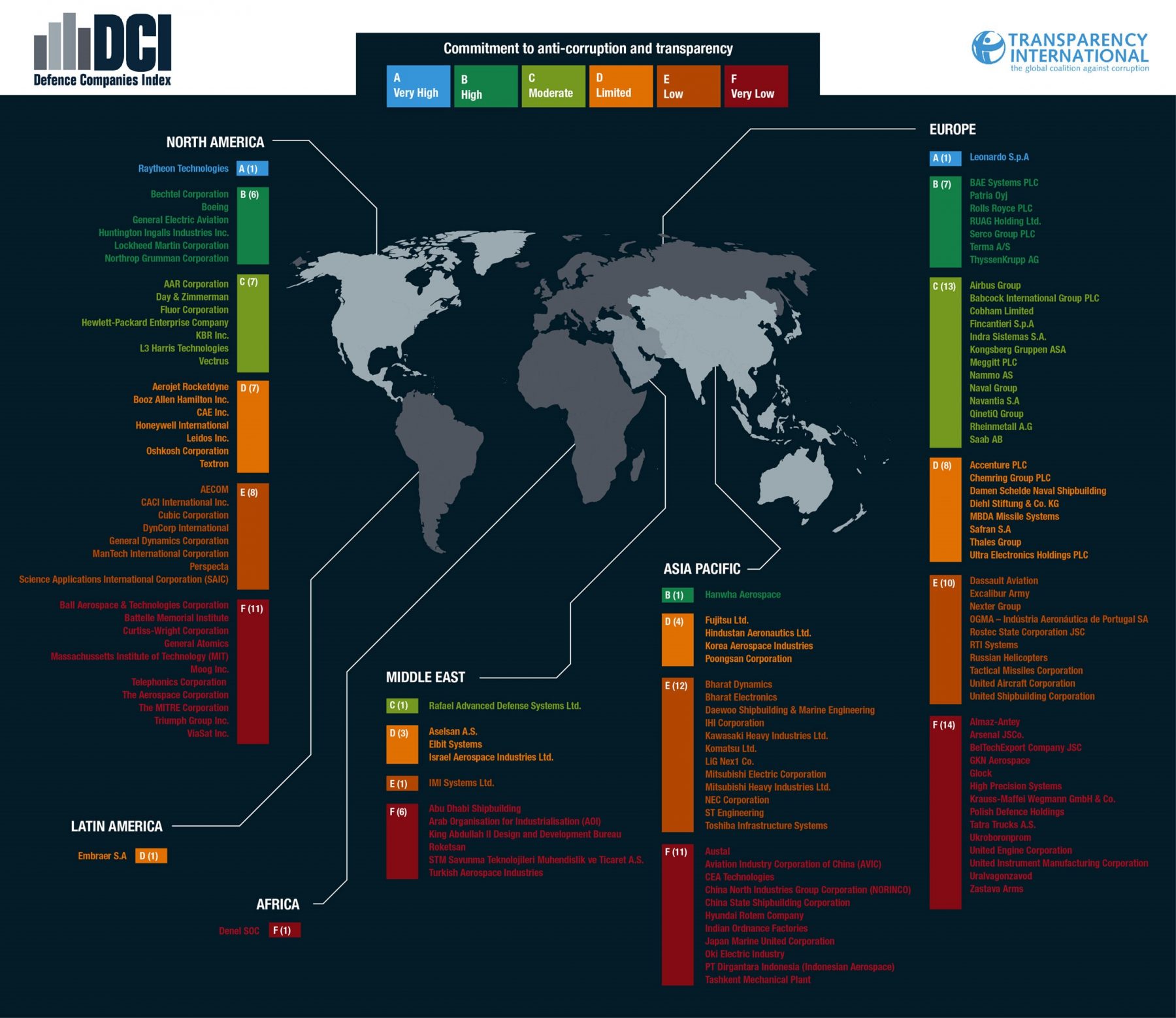

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) assesses the levels of public commitment to anti-corruption and transparency in the corporate policies and procedures of 134 of the world’s largest defence companies. By analysing what companies are publicly committing to in terms of their openness, policies and procedures, the DCI seeks to inspire reform in the defence sector, thereby reducing corruption and its impact.

Our latest research catalogues conflict and corruption around the word – harm caused by leaving the privatisation of national security to grow and operate without proper regulation.

Post-Afghanistan, exploitation of global conflicts is big business. Most private military and security firms are registered in the US, so we are calling on Congress to take a leading role in pushing through meaningful reforms under its jurisdiction. The time has also come for accreditation standards to be enforced rather than only encouraged, at both a national and international level.

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence and Security, describes some of the dangers documented in our latest research paper.

Unaccountable private military and security companies continue to pursue partnerships that in recent years have led indirectly to the assassination of presidents and journalists, land grabs in conflict zones, and even suspected war crimes.

From Haiti to Saudi Arabia to Nigeria, US-based organisations – the firms that dominate the market – have found themselves associated with a string of tragedies, all while their sector has grown ever-more lucrative.

Transparency International Defence and Security’s latest research – ‘Hidden Costs: US private military and security companies and the risks of corruption and conflict – catalogues the harm playing out internationally as countries increasingly seek to outsource national security concerns to soldiers of fortune.

Hidden costs from the trade in national security

While the US and other governments have left the national security industry to grow and operate without proper regulation, the risks of conflict being exploited for monetary gain are growing all the time.

Hidden Costs documents how the former CEO of one major US private military and security company was convicted – following a guilty plea – of bribing Nigerian officials for a US$6bn land grab in the long-plundered Niger Delta.

Our research also highlights that the Saudi operatives responsible for Jamal Khashoggi’s savage murder received combat training from the US security company Tier One Group.

Arguably most damning are the accounts from Haiti, where the country’s president was killed last year by a squad of mercenaries thought to have been trained in the US and Colombia.

Pressing priority

Many governments around the world argue that critical security capability gaps are being filled quickly and with relatively minimal costs through the growing practise of outsourcing.

Spurred on by the US government’s normalisation of the trade, US firms are growing both their services and the number of fragile countries in which they operate.

The private military and security sector has swelled to be worth US$224 billion. That figure is expected to double by 2030.

The value of US services exported is predicted to grow to more than $80 billion in the near future, but the industry and the challenge faced is global.

The risks of corruption and conflict in the pursuit of profits are plain.

These risks are as old as time. But their modern manifestations in warzones must not be left to spill over. The 20-year war in Afghanistan cultivated dynamics that threaten further damage, more than a decade after governments first expressed their concerns.

Required response

International rules and robust regulation are urgently needed. We need measures that ensure mandatory reporting of private military and security company activities. The Montreux Document lacks teeth, operating as it does as guidance that is not legally binding. Code of conduct standards must also become mandatory for accreditation, rather than purely voluntary.

Most private military and security firms are registered in the US. So Transparency International Defence and Security is also calling on Congress to take a leading role in pushing through meaningful reforms under its jurisdiction. There is an opportunity arriving in September, when draft legislation faces review.

Policymakers have long been aware of the corruption risks and the related threats to peace and prosperity posed by this sector. The time for action is well overdue. No more Hidden Costs.

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) assesses the level of commitment to transparency and anti-corruption standards in 134 of the world’s largest defence companies across 38 countries.

Data from the DCI 2020 reveals that although most of the world’s largest defence companies have publicly available ethics and anti-corruption programmes in place, the majority are still not transparent about their procedures to deal with the highest corruption risk areas, such as their supply chains, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures and offsets. Even where policies and procedures do exist, the DCI finds that many companies do not publish any information to indicate that they take steps to assure themselves of their effectiveness and implementation.

This report presents the key findings from the DCI 2020, broken down by the most significant risks facing companies operating in the defence and security sector.

By Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy – Transparency International Defence & Security

Nearly three-quarters of the world’s largest defence companies show little to no commitment to tackling corruption. That’s the headline finding from our newly published Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI). It assesses 134 of the world’s leading arms companies, ranking their policies and approach to fighting corruption from A to F.

The statistic is deeply concerning, if not altogether surprising to those familiar with the defence industry. Reducing corruption in the defence sector is imperative to guarantee safety and security. Yet, a veil of secrecy, invoked ostensibly in the interests of national security, shrouds the defence sector’s activities making it especially vulnerable. The widespread use of middlemen, whose identities and activities are kept secret, further limits oversight. The impact of corruption in the arms trade is particularly pernicious. The high value of defence contracts means that huge amounts of public money may be wasted, instead of being spent on essential public services. Corruption can encourage the excessive accumulation of arms, increase the circumvention of arms controls and facilitate the diversion of arms consignments to unauthorized recipients, perpetuating conflict and costing lives and undermining democracy.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, of the world’s 10 largest importers of major arms between 2015-2019, eight countries – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq and Qatar, UAE, China and India – are at high, very high or critical of corruption in the defence sector as measured by our Government Defence Integrity Index, the DCI’s sister index. Critical risk of defence sector corruption means major arms are sold to countries where they are likely to further fuel corruption, and where appropriate oversight and accountability of defence institutions is virtually non-existent.

The findings of the DCI add to this worrying picture. Nearly two thirds (61%) of the companies assessed show no clear evidence of policies or processes to assess and manage risk in markets they operate in. In addition, only 10% of the companies actively disclose full details of countries in which they and their subsidiaries operate, leaving a major gap in transparency and oversight of corporate activity.

Click here to view full screen.

The DCI has revealed that many companies score well on the quality of their internal anti-corruption measures, such as public commitments to fighting corruption and processes to prevent employees from engaging in bribery. However, because most companies publish no evidence on how these policies work in practice, it is impossible to know whether they are actually effective. Many firms do not publicly acknowledge they face increased risks when doing business in corruption-prone markets nor do they have apparent measures in place to identify and mitigate these risks. Few take measures to prevent corruption in ‘offsets’ – controversial side deals that involve a company reinvesting some of the proceeds of an arms deal into the customer’s economy but are banned in other sectors because of the corruption risks such deals pose – and most do little to counter the high-risk of bribery associated with using agents and intermediaries to broker deals on their behalf.

It is essential that companies have procedures in place to deal with these often opaque and high-risk aspects of the defence sector – including agents and intermediaries, joint ventures, offset contracting and operating in geographies considered at high risk of corruption.

We urge defence companies to increase corporate transparency through meaningful disclosures of:

- their corporate political engagement – a particularly high-risk issue in the defence sector -including their political contributions, charitable donations, lobbying and public sector appointments for all jurisdictions in which they are active;

- their procedures and the steps taken to prevent corruption in the highest risk areas, such as their supply chain, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures and offsets;

- procedures for the assessment and mitigation of corruption risks associated with operating in high-risk markets, a major risk for defence companies, as well as acknowledgement of the corruption risks associated with such practices;

- beneficial ownership and advocate for governments to adopt data standards on beneficial ownership transparency;

- all fully consolidated subsidiaries and non-fully consolidated holdings, and to state publicly that they will not work with businesses which operate with deliberately opaque structures; and

- the nature of work, their countries of operation and the countries of incorporation of their fully consolidated subsidiaries and non-fully consolidated holdings.

The DCI provides a roadmap for better practice within the defence industry. It promotes appropriate standards of anti-corruption and transparency of policies and procedures suited to the risks faced in the defence sector. Adopting these will not only reduce corporate risk, but also increase accountability and reduce the risk of corruption in the sector more widely.

ARMS INDUSTRY MUST DO MORE TO IMPROVE QUALITY AND TRANSPARENCY OF ANTI-CORRUPTION MEASURES

February 9, 2021 – Nearly three-quarters of the world’s largest defence companies show little to no commitment to tackling corruption, new research from Transparency International reveals.

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) is the only global index that measures the commitment to transparency and anti-corruption of the world’s leading defence companies.

Key findings:

- Just 12% (16) of the 134 companies assessed receive a top ‘A’ or ‘B’ ranking, demonstrating a high level of commitment to anti-corruption.

- 73% (98) received a ‘D’ or lower, indicating little commitment to transparency and anti-corruption.

- Of the 36 companies that scored a ‘C’ or higher, 21 are based in Europe and 13 are headquartered in North America.

Analysis of the results reveals that most companies score lowest in business areas that face the highest risk of corruption.

Many firms do not publicly acknowledge they face increased risks when doing business in corruption-prone markets nor do they have measures in place to identify and mitigate these risks. Few take measures to prevent corruption in ‘offsets’ – controversial sweeteners often bolted on to defence contracts – and most do little to counter the high risk of bribery associated with using agents and intermediaries to broker deals on their behalf.

Many companies score well on the quality of their internal anti-corruption measures, such as public commitments to fighting corruption and processes to prevent employees from engaging in bribery. However, because most companies publish no evidence on how these polices work in practice, it is impossible to know whether they are actually effective.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“These results reveal the defence sector remains mired in secrecy with companies often displaying inadequate policies and procedures to safeguard against corruption. With nearly three-quarters of companies failing to achieve a ‘C’ grade, clearly much more needs to be done. Given the well-established link between corruption and conflict, failure to do this will cost lives.

“Despite the overall picture looking bleak, there are some signs of progress in these results. Greater transparency and disclosure contribute to meaningful oversight and reducing corruption in the defence sector. Companies that improve both the quality and transparency of their anti-corruption efforts will see they are not only helping reduce human suffering but also aid to the promotion of the rule of law, which will benefit companies wishing to do their business in a clean way.”

The defence industry is a prime target for corruption because of the vast amount of money involved (global military expenditure in 2019 was estimated at more than $1.9 trillion), the close links between defence contracts and politics, and the notorious veil of secrecy under which the sector operates.

The impact of corruption in the arms trade is particularly serious. The value of defence contracts means that huge amounts of public money can be wasted, instead of being spent on essential services. Corruption perpetuates conflict and costs lives when troops are equipped with inadequate equipment and corrupt officials use gains from defence deals to strengthen their personal positions and undermine democracy.

The DCI provides a roadmap to better practice within the defence industry. It promotes appropriate standards of anti-corruption and transparency of policies and procedures suited to the risks faced in the defence sector. Adopting these not only reduces corporate risk, but also in turn helps to increase accountability and reduce the risk of corruption in the sector more widely.

We call on defence companies to commit to greater corporate transparency by increasing meaningful disclosures of:

- How they assess and mitigate the risks associated with operating in corruption-prone countries and publicly acknowledge the heightened risks of doing business in these markets;

- The anti-corruption programmes that are in place and the implementation of their policies and procedures;

- Measures to prevent and tackle corruption in all high-risk business areas, including the use of intermediaries, relationships with suppliers, joint ventures, offsets and interactions with public officials;

- Data that demonstrates the effectiveness of their anti-corruption programmes, such as staff surveys, audits and data regarding the use of whistleblowing hotlines and sanctions of transgressions;

Notes to editors

The DCI results can be found here – https://ti-defence.org/dci/

Global military expenditure was more than $1.9 trillion in 2019, according to SIPRI estimates – https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2020/global-military-expenditure-sees-largest-annual-increase-decade-says-sipri-reaching-1917-billion

Of the world’s 10 biggest importers of arms in 2019, eight are at high risk of corruption in the defence sector according to the DCI’s sister index – the Government Defence Integrity Index https://ti-defence.org/gdi/

Of these eight, five (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq and Qatar) are deemed to be at a ‘critical’ risk of defence sector corruption, meaning a large number of weapons are delivered to countries where they are likely to further fuel corruption, and where appropriate oversight and accountability of defence institutions is virtually non-existent.

About the Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Transparency (DCI)

The DCI analyses the commitment to transparency and anti-corruption in the world’s 134 largest defence companies.

It analyses publicly available information to assess the quality, extent and availability of anti-bribery and corruption policies and procedures in 10 key areas where increased commitment to anti-corruption ad transparency of information could reduce corruption risks in the defence industry.

The DCI does not measure corruption or how well a company’s anti-corruption measures work in practice as most disclose nothing on whether their polices and procedures are effective. A high DCI score does not indicate a company is immune to corruption – even companies with the most robust anti-corruption measures face risks and, in some cases, incidents of corruption.

The DCI follows two previous corporate indices published in 2015 and 2012, known as the Defence Companies Anti-Corruption Index. Due to significant changes in the aim, focus, methodology and question set of the 2020 index, any comparison with previous indices is not possible or appropriate.

About Transparency International – Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

+ 44 (0)79 6456 0340

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) seeks to assess the levels of commitment to anti-corruption and transparency in the corporate policies and procedures of 134 defence companies worldwide.

This document outlines the key methodological features of the DCI 2020, to provide further insight into the assessment process, scoring and implications of the index. The new formulation of the DCI 2020 reflects the substantial feedback received from a range of stakeholders as part of a comprehensive public consultation, which covered both the question set and the methodology itself. The DCI 2020 represents our commitment to promoting greater openness and transparency in the defence sector to help reduce corruption, build public trust, reassure investors, and build constructive relationships between companies and their employees and customers.

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) seeks to assess the levels of commitment to anti-corruption and transparency in the corporate policies and procedures of 134 defence companies worldwide.

We have identified 10 key areas where increased commitment to anti-corruption and transparency of information could reduce corruption risks in the defence industry. These risk areas form the

main structure of this Questionnaire and Model Answer (QMA) document.