Show Index: gdi

By Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research, and Léa Clamadieu, Research Project Officer

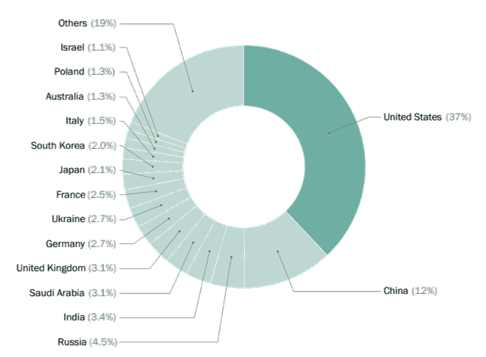

In 2024, global military expenditure rose for the tenth consecutive year, reaching an unprecedented $2.7 trillion. All five geographical regions of the world recorded an increase in military expenditure. Significantly, according to SIPRI, NATO members alone accounted for $1.5 trillion—around 55 per cent of the total global spending. This figure is set to grow further following the Alliance’s June 2025 commitment to increase national defence budgets to 5 per cent of GDP.

While this surge underscores the renewed emphasis on collective security, it also brings significant corruption and governance risks. Defence budgets are often shrouded in secrecy, with parts of spending channelled through off-budget mechanisms that escape parliamentary scrutiny and public oversight. As highlighted by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in his report The Security We Need, such opacity erodes political control over public finances; heightens the risks of inefficiency, corruption and mismanagement; and diverts resources from essential public services and sustainable development. Defence procurement processes -frequently among the least transparent areas of government – are also vulnerable to corruption, waste, and political capture.

This is not just a threat on paper – it is very much real: A recent investigation by La Lettre and partner news outlets brought to light how criminal networks exploit corruption loopholes to win contracts awarded by the NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA), and how kickback schemes built a system of corruption between the NSPA and former staff. Pressure on audit institutions and lack of support for whistleblowers was found to further limit oversight and meaningful anti-corruption measures.

This moment presents a risk, but also an opportunity. The NATO Building Integrity programme, which works to promote good governance and integrity reform, has made a positive contribution. However, with unprecedented resources being mobilised, NATO member countries can strengthen transparency, accountability, and governance frameworks to ensure that all military expenditures serve their intended purpose.

To support this, we have has identified examples of best practice from across NATO countries, recognising that systems and approaches differ – but that valuable lessons can be shared. Drawing on insights from our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), we highlight a selection of good practices across three key risk areas:

- Policymaking: Defence sector oversight and civil society inclusion

- Financial: Transparency in actual defence spending

- Procurement: Integrity and openness in defence purchases

At the core of the examples is embedding integrity in the defence sector, defined here as “institutional resilience to corruption”, these cases demonstrate that strong oversight and openness are not obstacles to security—they are essential foundations for it.

Photo by Marek Studzinski on Unsplash

Policymaking: Oversight and CSO inclusion

Identifiable and effective parliamentary defence and security committee exercising short- and long-term oversight

Members of parliamentary Defence Committees should comprise individuals with defence sector expertise experience in the field of security for oversight to be effective. In terms of short-term oversight of the Defence Committee, the regularity of committee’s meetings, the depth of the debate as well as public access are key to promote efficient parliamentary oversight. In Latvia, the Defence Committee meets at least twice a week and issues budget amendments and recommendations which are developed in collaboration with ministries. Issues debated are legislative, including preparing draft legal acts and policy planning documents, and non-legislative, such as informative or investigative meetings. The same frequency of meetings is noted in Belgium, where the debates from representatives are also thoroughly documented and publicly available with dates and integral text of the debate documented in a question-and-answer format.

The Committee should also be able to conduct long-term investigations such as current defence activities or military operations like in the Netherlands and be able to invite ministries and other institutions to report on specific issues like in Latvia. Once recommendations are made by the Parliamentary Committee, it is important that the Ministry of Defence (MoD) acknowledge and incorporate them. For instance, in the Netherlands there is first an internal debate on the topic at hand and external with the Ministry. If a specific Member of Parliament is not satisfied with the result of discussions, they can put the recommendation into a motion for the plenary to vote on. If the majority votes in favour, the ministry is obliged to implement the recommendation.

Policy, or evidence, of openness towards civil society organisations (CSOs) when dealing with issues of corruption

It is essential that CSOs operate free from government interference and intimidation and more importantly that defence and security institutions engage and work regularly with them on corruption issues. This engagement can take different forms. In Norway, the MoD created the Centre for Integrity in the Defence Sector (CIDS) in 2012 which seeks to promote and enhance professional integrity and good governance in the defence and security spheres. Its work includes collaborating with a range of CSOs. Moreover, in the Netherlands, military personnel often work together with civilians and civil society organisations, with expertise in public administration, government, law enforcement and justice, in mission areas. CSOs can offer practical and tangible inputs into the defence policymaking and accountability processes.

Financial: Transparency of actual defence spending

Good practice requires that all spending related to personnel, procurement, R&D and other categories should be disclosed with very few exceptions. In Latvia and the United Kingdom, actual defence spending is published annually in a comprehensive format and includes detailed explanations for all audiences (expert and non-experts). Good practice also requires MoDs to explain the variances between the published budget and actual spend. The UK, for example, publishes a 200-page report on annual accounts and performance with detailed expenditures and explanations. Additionally, actual spending should be published within six months after the end of the financial year and scrutinised by an independent oversight institution, as in the case of the UK.

Procurement: Integrity and openness in defence purchases

Oversight of defence procurement

Oversight of defence procurement should be independent and effective. In Norway, in addition to internal auditing of defence procurements by the Internal Auditor Unit and the Contract Audit section, external auditing is conducted by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG). The OAG may also initiate in-depth investigations of the defence sector. In Finland, the Parliamentary Committees also discuss procurement. These oversight bodies work free from undue influence from the executive or military. In Finland, Latvia and Norway, the oversight bodies are active in summoning witnesses and documents, demanding explanations, and issuing recommendations and conclusions that must be followed. Moreover, they also publish reports on their findings, which are accessible to the public.

Photo by SaiKrishna Saketh Yellapragada on Unsplash

Transparency of actual purchases

Good practice standards in defence procurement requires that actual defence purchases are made public with almost no exceptions. The amount spent, reason for expenditure and companies involved should be also disclosed in an Excel format for readability. In Finland, all defence purchases are published on the ‘Hilma’ system – a digital notification channel where public sector buyers announce their upcoming procurement plans, ongoing tendering procedures and the results of tenders that have already ended; it is owned by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy. In Norway, all contracts above a set threshold must be published in DOFFIN (the Norwegian National Database for Public Procurement) and TED (Tenders Electronic Daily). In the UK, data on all spending above £25,000 is available in an accessible format, viewable online and published monthly.

Open competition

All procurement should as far as possible be based on open competition and the percentage of singled source contract be transparent. Additionally, in terms of oversight, all single-source procurements need to be justified and scrutinised by an oversight body like Supreme Audit Institution, as in the case of Latvia and Norway.

As military budgets surge across NATO member countries and beyond, the need for arming with integrity – strengthening institutional resilience to corruption risk – and embedding good practice standards in the defence sector has never been greater. Rising military spending can strengthen security but only if matched by equally strong systems of accountability, transparency, and public oversight. The examples highlighted show that practical measures—such as empowered parliamentary committees, open engagement with civil society, transparent reporting, and independent procurement audits—can make a tangible difference.

By Leah Pickering, Programme Officer – Transparency International Defence & Security

“Trick or treat?”

It’s a familiar call every 31 October. But twenty-five years ago, another call echoed through the corridors of the United Nations in New York. An active and vibrant civil society movement, joined by a handful of determined member states, were demanding something far more profound: power, protection, participation, peace, and security.

For years, these advocates had been knocking on closed doors, urging the UN to confront the gendered realities of conflict and the exclusion of women from decision-making. At last, the door opened.

On 31 October 2000, the Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS), a landmark decision that recognised both the unique security challenges faced by women in conflict and their crucial contributions to peace. Centred on the four pillars of participation, protection, prevention, and relief and recovery, it called for women’s full inclusion in peace and political processes, stronger measures to prevent and respond to gender-based violence, and the advancement of gender equality across all peace and security efforts.

It was a historic shift from seeing women as passive victims of war to recognising them as active agents of peace and positive change. In the years that followed, more than ten additional resolutions expanded this vision, and over one hundred countries developed National Action Plans to bring it to life. Regional organisations such as the African Union, the European Union, and NATO integrated WPS principles into their frameworks, helping to embed gender perspectives across peace and security institutions.

Yet even amid these gains, not all doors have opened equally. Women continue to be underrepresented in peace negotiations, and when they do participate, their involvement is often symbolic rather than substantive. Implementation has frequently ignored the perspectives of women from the Global South, LGBTIQ+ individuals, and other marginalised groups, leaving significant voices unheard. The spaces where women’s rights organisations once influenced and defended the agenda are shrinking, and those most affected by conflict and violence are often the first to be excluded.

No tricks, just truth: while the WPS agenda has achieved much, persistent gaps and blind spots continue to undermine its promise.

One of the most concerning of these gaps is corruption.

Corruption impacts every pillar of the WPS framework, silently shaping whose voices are heard, whose rights are protected, and who remains unsafe. In defence and security sectors, corruption manifests in deeply gendered ways such as sexual extortion in exchange for aid or safety, bribery that denies survivors justice, and patronage networks that exclude women and marginalised communities from decision-making. These are not small flaws in governance. They are daily realities that determine who is safe, who is heard, and who gets justice.

In fragile and conflict-affected settings, corruption and gender-based violence feed off each other. From peacekeepers implicated in sexual exploitation and abuse, to officials colluding with traffickers, to survivors silenced by corrupt courts, the pattern is disturbingly familiar. Corruption weakens institutions, insecurity rises, gender-based violence spreads, and impunity deepens. The result is a vicious cycle that corrodes both peace and trust.

Despite these harms, corruption has remained a persistent threat. The WPS and anti-corruption agendas have developed in isolation, speaking different policy languages, working through different systems, and drawing on different funding streams. Corruption is often treated as a technical problem of governance, while WPS is seen as a political and human one. The result is a blind spot that allows abuse and insecurity to persist unchecked.

Twenty-five years after its adoption, the WPS agenda must face the truth: corruption continues to undermine its promise of peace and equality. Transparency International Defence and Security’s new policy brief, Closing the Blind Spot: Confronting Corruption to Advance Women, Peace and Security, argues that integrating anti-corruption into the WPS agenda is not an optional extra – it is essential. Recognising corruption as a driver of gendered insecurity is vital if prevention, protection, participation, and recovery are to be realised in practice rather than only in principle.

The brief calls for five key steps:

- Acknowledge the risk by naming sexualised corruption explicitly in WPS frameworks.

- Assess with a gender lens by embedding gender-sensitive corruption risk assessments into security sector reform, disarmament, demobilisation, reintegration, and peacekeeping processes.

- Embed safeguards through survivor-safe oversight and reporting mechanisms.

- Enable accountability by empowering parliaments, national human rights institutions, and civil society watchdogs.

- Align global tools by connecting WPS, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and United Nations Convention Against Corruption obligations into a coherent framework for integrity and inclusion.

Twenty-five years after UNSCR 1325 first opened the door, the WPS agenda still inspires hope. Yet it also demands honesty. If we are to move from promise to practice, we must unmask corruption and confront the structures that keep women, girls and LGBTQI+ individuals unsafe.

No tricks, just truth: peace that ignores corruption will always be haunted by inequality, insecurity, and silence.

It is time to face the ghosts and build peace that is not only promised but practiced.

Civil war has been raging in Sudan for soon two years with no end in sight. Its violence and destruction have caused a “humanitarian catastrophe”. Yet, as the conflict remains at the margins of media and public attention, so does one of its main drivers: corruption.

Weak defence governance and failed security sector reforms have played an important role in driving the conflict. Over the last six years, Sudan has experienced high levels of political instability, writes Emily Wegener.

Whether as a driver of the protests in 2018-2019 that forced President Omar al-Bashir out of power, or a as contributing factor to the October 2021 military coup staged by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that halted the democratic transition process, corruption continuously contributed to this volatility. Regimes fell, but the power structures and the corruption networks in and around the military and security forces survived. These networks then fuelled tensions between the SAF and RSF, which reached their breaking point in April 2023 with the outbreak of armed conflict between the two groups.

From the onset of the conflict, corruption has driven the violence. Failure to agree on a way forward in the country’s security sector reform (SSR) – the process of improving a country’s police, military and related institutions to ensure they are effective, accountable and respect human rights – is widely seen as one of the key reasons for why the democratic transition failed. Placing the RSF under civilian control and enhancing democratic scrutiny of the SAF were two of the most contentious questions in the SSR process.

But what made improving the oversight and accountability of these groups so contentious? Our 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) assessed the corruption risk as critical throughout Sudan’s defence institutions, concluding that “corruption is widespread in the sector and there are virtually no anti-corruption mechanisms”. Civilian democratic control and external oversight of defence institutions were also found to be non-existent.

An absence of accountability enabled both the SAF and the RSF to repurpose the state’s defence and security institutions to enrich high-ranking security officials and create an economy dominated by military interests. Companies owned by SAF officials have long controlled lucrative private sectors, from telecommunications to meat processing, to the detriment of public investment and sustainable economic growth. Meanwhile, the RSF controls most of the country’s gold trade – a significant income stream, considering that Sudan was the third-largest gold-producer on the continent in 2023. By the time the war broke out, the RSF owned around 50 companies, acquired largely by reinvesting the profits from gold trade into other industries. Transition to civilian rule would have meant placing the SAF under civilian oversight; for the RSF, integration into the army. When the RSF was not ready to give up its advantages, or accept this level of accountability, it declared war.

Why we produced ‘Chaos Unchained’

In February 2025, nearly two years the outbreak of the war, Sudan is facing starvation and the world’s largest displacement crisis. An estimated 30% of the population, over 11 million people, have been forced to leave their homes. According to the UN Secretary General’s latest report, over 25 million people live in food insecurity, including over 750,000 people living in conditions comparable to famine, as defined by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). Both sides, and the RSF in particular, are reported to have perpetrated ethnic cleansing and sexual violence.

Yet, the attention paid to the conflict is scarce. Sudan rarely makes the headlines. Across the international community, the focus is elsewhere. To shed light on this ‘forgotten conflict’ and its drivers, we have produced a 10-minute video looking at the origins of Sudan’s turmoil. Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan examines how corruption, kleptocratic plunder of the country’s resources and lax enforcement of arms embargoes have contributed to the ongoing conflict and the humanitarian catastrophe that comes with it.

Possible solutions

Governments and private actors can take steps to reduce the role of corruption in prolonging the fighting, and to limit the chance of relapse after a political solution is negotiated.

At international level, the UN, the EU and their Member States can:

- Recognise the links between corruption in the defence and security sector and the violence and elevate the importance of addressing corruption in the conflict resolution agenda. A strong precedent is the UN Security Council Resolution 2731/2024 on the situation in South Sudan, where the Council recognises that “intercommunal violence in South Sudan is politically and economically linked to national-level violence and corruption”, and stresses the need of effective anti-corruption structures to ensure and finance the political transition and humanitarian needs of the population.

- Explore the links between arms diversion and corruption, and the resulting circumvention of UN arms embargo and human rights abuses in the Darfur region. Existing mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Sudan and the Security Council’s Panel of Experts can contribute to improving the evidence base on the role of corruption, especially in the defence and security sectors, in fuelling the war and humanitarian crisis.

- Prioritise strengthening the rule of law and anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding. Placing the SAF and the RSF and their economic assets and activities under civilian oversight is a key step toward transparent and accountable defence and security forces. A long-term, transformative, and inclusive SSR process will be the most necessary but also the most contentious element of any negotiated solution to the conflict in Sudan. Additionally, any peacekeeping or peacebuilding interventions will need to firmly prioritise anti-corruption as a conflict prevention measure.

At national level, the governments of arms exporting countries can:

- Strengthen arms export policies and implementation guidelines. Foreign-made weapons and military equipment are being diverted into Darfur despite a long-standing UN Security Council arms embargo. Arms exporting countries can use our GDI to better assess the risk of corruption in defence institutions. Robust corruption risk assessments can help to curb diversion risks in arms sales to Sudan and the regional partners of the SAF and the RSF.

- Better regulate defence offsets. In connection with major arms sales, defence companies often negotiate lucrative offset packages with even less transparency than the arms sales. Our research has shown that defence company offsets can contribute to fuelling conflict dynamics, including in countries like Sudan by supporting industries in the UAE that help finance Sudanese armed actors. Enhancing internal and external transparency and oversight around these deals can mitigate risks of contributing to natural resource laundering for armed groups and fuelling conflict dynamics such as the one in Sudan.

Sudan shows that fighting corruption is not separate from discussions on ceasefires, political negotiations and peace processes. Integrating anti-corruption measures and fostering transparency and accountability in Sudan’s defence and security sector is key to the long-term success of any negotiated political solution.

You can watch Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan here.

Register here to join our webinar on Thursday, 6 February, in which we discuss the root causes of the conflict and pathways to peace with an expert panel.

At a time of mounting geopolitical tensions and growing instability, governments around the world are spending record sums on defence and security, writes Yi Kang Choo, our International Programmes Officer.

Recent data highlights this move towards increased militarisation. PwC’s 2024 Annual Industry Performance and Outlook reports a 7% increase in overall revenues among the top 11 defence companies in 2023. Leading contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and BAE Systems are grappling with record-high defence order backlogs, with an 11% increase in value to $747 billion. Meanwhile, an analysis by Vertical Research Partners for the Financial Times forecasts that by 2026, the leading 15 defence contractors will nearly double their combined free cash flow to $52 billion compared to 2021.

These figures demonstrate a sector on an upward trajectory, buoyed by heightened demand and increased defence budgets largely due to escalating geopolitical tensions and conflicts globally. Reinforcing this trend, the 2024 Global Peace Index highlights an increase of, while global military expenditure surged to an unprecedented $2.443 trillion in 2023, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

In this blog, we will delve into the importance of strong governance standards for defence companies, and outline the role companies, boards, and investors (who are susceptible to the risks of the supply side of corruption and bribery) in fostering a culture of integrity, accountability and transparency within the sector.

At Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), we have long raised concerns about the risks associated with surging military spending. In our Trojan Horse Tactics report, we show that increased defence spending without appropriate oversight often correlates with rising corruption risks. In countries that are not equipped with the requisite institutional safeguards, an influx of funds is most likely to benefit corrupt actors across defence establishments, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that prioritises private gain over peace and security outcomes. Nevertheless, robust governance standards are not only essential for officials and government (the demand side of corruption), but are equally vital for defence companies and contractors on the supply side, particularly as the stakes continue to rise.

The Profit Boom: A Double-Edged Sword

For many in the defence sector, the current boom in profits is a cause for celebration. However, the rapid influx of funds brings increased risks to the industry, too. Despite widespread acknowledgment within the sector that corruption is harmful to business, companies continue to face challenges in effectively implementing preventative measures.

Corruption in the defence industry is also persistent. The combination of complex procurement processes and high value contracts creates a fertile ground for opaque practices, further exposing governance vulnerabilities and inefficiencies within companies. Notably, some of the world’s largest defence companies have faced significant allegations of corruption in recent years:

In 2014, a UK subsidiary of AgustaWestland S.p.A (now under Leonardo) was fined €300,000 – while its parent company AgustaWestland was fined €80,000 – to settle an Italian investigation into allegations of bribery relating to the sale of 12 helicopters to the Indian military. In addition, the court ordered the confiscation of €7.5 million in company profits.

In January 2017, Rolls Royce entered into record-breaking settlements in the US, UK, and Brazil to resolve numerous bribery and corruption allegations involving its . The UK and US settlements involved Deferred Prosecution Agreements worth £497 million and $170 million respectively, while a leniency agreement with Brazilian prosecutors amounted to almost £21 million.

In 2021, UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) secured a corporate conviction against GPT Special Project Management, a former subsidiary of Airbus. GPT pleaded guilty after a near decade-long investigation to a single count of corruption and was ordered to pay over £30m in confiscation, fines, and costs.

In November 2024, a fraud investigation was launched into suspected bribery and corruption at Thales in relation to four of its entities by the Parquet National Financier in France and the UK’s SFO. Thales denied the allegations and said that it complied with all national and international regulations. The investigation is still ongoing. Likewise, earlier in June 2024, triggered by two separate investigations of suspected corruption, money laundering, and criminal conspiracy linked to Thales’ arms sales abroad, police in France, Spain, and the Netherlands also conducted searches in its respective country offices. A spokesperson for Thales confirmed to Reuters that searches had taken place but gave no further details beyond saying that the company was cooperating with authorities.

As seen in the examples above, corruption can also be costly. When allegations are levelled against a company, lengthy investigations divert resources and cause reputational damage. Convictions or settlements may result in large fines, claims for damages and ultimately exclusion from key markets.

And the costs to companies are likely to rise. Increasing shareholder activism and Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG)-driven investment strategies meant that investors and stakeholders are scrutinising companies’ ethical practices more than ever. Defence firms that fail to prioritise anti-corruption and transparency risk alienating their stakeholders and jeopardising long-term growth.

The Shadow of Lobbying and Undue Influence

With defence companies forecast to have more cash available in the coming years, spending on share buybacks, increased dividends, and expansion will not be their only focus – it’s also vital not to ignore the risks of companies exerting undue influence on government defence policy.

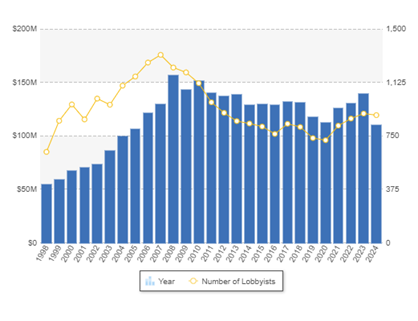

According to Open Secrets, in 2024, up to $110 Million was spent by defence industries to lobby the US government (including political candidates and committees) in securing government defence contracts, earmarks, and influencing the defence budget to make certain contracts more likely. Amongst the 896 lobbyists, more than half of them (63.28%) consist of former government employees – a stark example of the ‘revolving door’ between the public and private sector which is especially pervasive situation in the global defence industry where significant conflicts of interest may occur if not appropriately regulated.

Whilst traditional lobbying activity with policy makers and institutions to exchange ideas and influence certain policies forms an essential part of the democratic process, the amount of money defence companies spend on lobbying activities, combined with a lack of transparency, may mutate lobbying processes into privileged access. It can also create opportunities to wield considerable influence over politicians and officials responsible for shaping public policy, heightening the risk of policy decisions being disproportionately skewed in favour of individual companies rather than serving the broader public interest. Moreover, for governments and industry regulators, this underscores the need for stringent oversight and transparency measures to ensure that lobbying activities do not undermine democratic processes or market fairness.

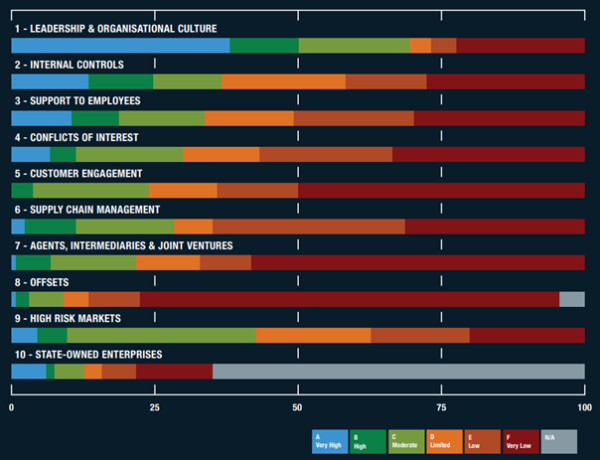

The Time to Act is Now: The Role of Companies, Boards, and Investors

Despite these challenges, the compliance and transparency efforts of companies should not be understated. According to the Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) 2020, most of the world’s largest defence companies have established publicly available ethics and anti-corruption programmes, with robust policies and procedures in place for employees to follow. Industry associations now also have dedicated ethics committees, and many companies participate in platforms such as the International Forum on Business Ethics (IFBEC) and the Defence Industry Initiative for Business Ethical Conduct (DII) which enabled ethics and compliance staff within major companies to access more resources and to receive more senior recognition for their work. However, there is still more work to do. Many major defence companies still do not publish or show no evidence of a clear procedure to deal with the highest corruption risk areas, such as their supply chains, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures, and offsets.

Companies have a crucial role to play to in building and strengthening policies, practices, and a culture of integrity, accountability and transparency within the defence sector worldwide. We call on companies to put anti-corruption and transparency at the very core of their corporate agenda, alongside promoting discussions on how to raise governance standards across the organisational, national, and regional forums in which they are part of. Companies are also encouraged to engage with civil society organisations and anti-corruption experts to exchange learnings, foster accountability, and encourage further employee engagement in the mitigation of corruption risks across the business.

Directors of companies should exercise their fiduciary duties effectively by holding executives accountable when proactive procedures and steps are not being taken to detect, prevent, and address corruption in the highest risk areas. They could also encourage the meaningful disclosure of the company’s corporate political engagement, especially any political and lobbying contributions, to uphold the reputation and long-term stability of the company as it poses a particularly high-risk in the defence sector.

Finally, investors in defence companies could emphasise anti-corruption transparency as an essential cross-cutting issue embedded within ESG initiatives, and to urge the companies in which they hold shares to increase meaningful disclosures of their ethics and anti-corruption programmes. Investors wield significant influence in shaping corporate behaviour, and by advocating for these changes, investors can drive long-term value creation while promoting ethical business practices.

The defence industry is at a critical juncture. As military spending and corporate revenues soar, the stakes for maintaining ethical governance have never been higher. Robust governance standards are essential – not only to mitigate corruption risks but also to uphold the sector’s integrity in an increasingly interconnected and scrutinised global landscape. By taking decisive action and establishing clearly defined, targeted processes, defence companies, boards, and investors can ensure that the industry remains resilient, competitive – and most importantly – aligned with the principles of transparency and accountability.

January 15, 2025 – Transparency International – Defence & Security (TI-DS) today launches a series of policy briefs examining the institutional resilience of the defence and security sectors in Nigeria, Tunisia, Niger and Mali.

Against a backdrop of democratic backsliding, political upheaval and mounting security threats, the briefs lay out clear, country-specific policy recommendations for tackling the corruption risks undermining effective defence governance and stability across West and North Africa.

Read the briefs: Nigeria | Tunisia | Niger | Mali

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence & Security, said:

“Transparency and accountability are not only moral imperatives but also practical necessities for effective defence and security sectors. The evidence outlined in these policy briefs clearly shows the effects of weak defence governance – where corruption is allowed to fester, peace and stability suffer. Our recommendations offer governments, policymakers, and civil society organisations a clear roadmap to tackle the corrosive effects of corruption on national security.”

Each policy brief offers a blueprint for improved institutional resilience in the defence and security sector, grounded in data from our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), the world’s leading assessment of corruption risks in government defence institutions.

The analysis draws on:

- Country-specific context: Recent political events, military spending, arms imports, and public opinion on governance and democracy.

- Institutional resilience assessment: A breakdown of existing corruption safeguards and vulnerabilities in defence governance, informed by GDI data and comparisons with regional peers.

- Policy recommendations: Practical steps, developed in partnership with Nigeria/CISLAC, TI Tunisia/IWatch, and TI Niger/ANLC for improving transparency, accountability and ultimately providing peace and security for citizens.

Country summaries

Systemic corruption continues to plague the defence sector and cause a major hindrance to security in the face of significant threats. Defence budgets and procurement processes remain largely opaque. Decisive reforms to boost transparency – especially in military spending – and the reinforcing of both accountability and civilian oversight are key pillars for long-term institutional resilience.

Defence governance suffers from weak legislative functions and limited scrutiny over a highly centralised executive. With critical information restricted, parliamentary and civilian oversight remain fragile. Enhanced dialogue with civil society, clearer legal frameworks on access to information and a commitment to establishing best-practice exceptions for genuine national security concerns would go a long way to improving resilience against corruption.

A severe lack of transparency and oversight surrounds military activities, particularly defence expenditure, procurement and disposal of military-owned assets. Opening dialogue with civil society, strengthening accountability and embedding corruption risk mitigation into military operations are essential steps for rebuilding trust and stability amid the country’s evolving political landscape.

Systemic weaknesses provide opportunities for the diversion of military funds and influence-peddling, compromising both equipment on the front lines and broader political and economic stability. Defence procurement is shrouded in secrecy, blocking effective scrutiny of military purchases and how equipment is used. The release of key procurement information and auditing mechanisms are vital to creating sustainable institutional resilience against corruption.

This policy brief highlights findings from the 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) that are pertinent for a path to enhanced institutional resilience to corruption in Nigeria’s defence governance.

It is based on a close reading of the GDI results for Nigeria, policy literature, recent news reports, and context and problem analyses conducted by the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC) – the Transparency International (TI) national chapter in Nigeria.

This policy brief aims to highlight findings from the 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) that are most pertinent for a path to enhanced institutional resilience to corruption in Nigerien defence governance.

It is based on a close reading of the GDI results for Niger, policy literature, recent news reports, as well as a context and problem analysis conducted by Association Nigérienne de Lutte Contre La Corruption (ANLC) – the Transparency International (TI) national chapter in Niger.

This policy brief aims to highlight findings from the 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) that are most pertitent to enhancing institutional resilience to corruption risk in Tunisian defence governance.

It is based on a close reading of the GDI results for Tunisia, policy literature, news reports over the past decade, and context and problem analyses conducted by I WATCH – the Transparency International (TI) national chapter in Tunisia.

This policy brief aims to highlight findings from the 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) that are most pertinent to enhanced institutional resilience to corruption in the Mali’s defence sector.

It is based on a close reading of the GDI results for Mali, as well as context and problem analyses conducted by TI-DS, policy literature, and news reporting on Mali over the past decade.

Harnessing the power of collaboration, mutual learning, and knowledge exchange across our global Transparency International (TI) movement of over 100 chapters, Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) launched Defending Transparency: An advocate’s guide to counteracting defence corruption in August 2024. To bring this toolkit to life, we organised a series of Academy Day sessions to foster dialogue and offer hands-on training on how to effectively advocate for better anti-corruption standards in defence and security. Our International Programmes Officer, Yi Kang Choo, shares reflections on the most recent session held in Bangkok, Thailand.

On 30th November 2024, we brought together national experts from six TI Chapters across the Asia Pacific region: Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, South Korea, Pakistan, and Taiwan, for a dynamic one-day session focused on strengthening defence governance and anti-corruption advocacy through shared learning and collaboration.

The day began with an overview of the defence governance landscapes in the region. Chapter representatives shared their national experiences, highlighting challenges such as procurement practices, blurred public-private relationships in defence sectors, and limited civilian and parliamentary oversight. These discussions underscored the complexity of combating corruption and the need for innovative, context-specific solutions. Participants also candidly shared their frustrations and identified common obstacles faced by civil society in championing transparency and accountability in the defence and security sector.

One of the highlights of the day was the discussion of successful advocacy campaigns and the use of our 2020 Government Defence Integrity (GDI) Index. TI Taiwan demonstrated how the GDI alongside the chapter’s advocacy catalysed the formation of a dedicated team within the Ministry of National Defense’s (MND) Ethics Office to address the corruption risks identified in the index. TI Taiwan and the MND also co-hosted the International Military Integrity Academic Forum in 2023, fostering constructive dialogue on enhancing defence sector transparency. Similarly, TI Malaysia showcased how the GDI findings sparked public interest and facilitated further engagement with civil society in the traditionally closed and secretive defence and security sector.

These success stories inspired lively discussions, providing valuable lessons and strategies adaptable to other national contexts. We also shared findings from our latest report, Unlocking Access: Balancing National Security and Transparency in Defence. The report discusses how blanket national security exemptions are often used to justify withholding critical information, while public interest tests designed to balance the benefits of disclosing against the potential harm remain mostly absent from the cases considered. The report also features detailed case studies from five countries around the world at varying stages of progress in advancing access to information in their defence sectors, including Malaysia.

Finally, an interactive workshop followed, which encouraged participants to brainstorm and collaborate on national and regional advocacy opportunities, using the tools provided in our Advocacy Toolkit. Ideas such as fostering cross-border cooperation, engaging private sector stakeholders, and leveraging international forums like ASEAN and the Shangri-La Dialogue were central to the discussions. We also discussed how international transparency standards such as the 2013 Tshwane Principles could offer practical guidelines for governments to balance transparency and access to information with legitimate national security concerns. The session also reinforced the importance of regional and international solidarity amongst civil society in driving systemic change.

Throughout the day, the recurring theme was the importance of building and nurturing trust and partnerships. Whether engaging with defence institutions, civil society, or private companies, sustained dialogue and collaboration were seen as essential for creating lasting change. By the end of the session, participants left with actionable ideas, strengthened networks, and renewed motivation to engage on the topic moving forward. They were also invited to join our Global Defence Network, fostering further collaboration with like-minded chapters, civil society organisations, and experts worldwide.

Alvin Nicola (Democratic and Participation Governance Manager, TI Indonesia): “Fortifying alliances in the Asian region is an undeniable priority for all of us, TI Chapters. I am honoured to have the opportunity to exchange perspectives and explore collaborative steps that will further strengthen the integrity and stability of the defence and security sectors across the region.”

Dr Nausheen Wasi (Board Member, TI Pakistan): “Though, it was a brief interaction with colleagues in Bangkok, yet I thoroughly enjoyed meeting them all. I kept on thinking how the same work ideology — commitment to bring positive change in society — connects us all, regardless of diversity we inherit.”

The Academy Day reinforced our shared commitment to fighting corruption and enhancing governance of defence and security sectors in the Asia Pacific region. The lessons learned and partnerships forged will continue to guide our efforts to promote transparency and accountability in the defence and security sector. We look forward to deepening our collaboration and shared learning with Chapters across the TI movement to advance our vision of a world free from corruption in defence and security.

Defending Transparency: An advocate’s guide to counteracting defence corruption is available to read here.

Further insights from Armenia, Guatemala, Malaysia, Niger, and Tunisia illustrate access to information challenges

December 10, 2024 – New research from Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) underscores the need for better access to information in the defence sector to curb corruption, ensure accountability, and improve civic engagement.

Published today, Unlocking Access: Balancing National Security and Transparency in Defence shines a light on opaque defence sectors worldwide at a time of increased geopolitical tensions and global military spending reaching record highs of $2.4 trillion.

The report highlights challenges and good practices of transparency in defence budgets, procurement and policy processes using detailed case studies from Armenia, Guatemala, Malaysia, Niger, and Tunisia. The countries are at varying stages of progress in advancing access to information in their defence sectors and face a range of challenges, including conflict-driven secrecy, democratic backsliding, and stalled reforms.

Our analysis reveals that while international frameworks provide guidelines for transparency, implementation remains weak. Blanket national security exemptions are often used to justify withholding critical information, while public interest tests designed to balance the benefits of disclosing against the potential harm are mostly absent.

This lack of transparency increases the risk of corruption, mismanagement of funds, and fuels public distrust of the very institutions tasked with protecting citizens.

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence & Security, said:

“The defence sector remains one of the most secretive corners of government, making it a breeding ground for corruption. Striking a balance between national security and the public’s right to know is crucial to ensure accountability, but far too often governments tip the scales towards secrecy. It’s time for transparency to be the rule, not the exception.”

Case study insights

Armenia has kept high levels of defence spending because of its decades-long conflict with Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh territory, which recently concluded with major losses for Armenia. Access to information was enshrined in a 2003 national freedom of information law but has been severely curtailed by the 2024 states secrets law, which prohibits the release of information related to most defence spending.

Guatemala has endured a growing corruption crisis for the past decade, as the presidency and the powerful Public Prosecutor’s office stifled anti-corruption efforts, forced anti-corruption officials into exile, and blocked potential reform candidates from elections. As the Secretariat for Access to Public Information is required to work with the Prosecutor’s Office on access to information enforcement, implementation of the law has faltered until now.

Malaysia saw a peaceful power transition in 2018, but governance reforms – including access to information – have stalled, with the Official Secrets Act 1972 (OSA) severely limiting access to information. The OSA functions as the de facto national framework for access to information and overrules any other legislation on information access. There is little knowledge about the defence budget or expenditures, and almost no publicly available information about acquisition planning.

Niger experienced a military coup in July 2023 that has led to increased violence, stark reductions in foreign assistance, and a severe curtailing of access to information and other democratic rights. Even prior to the coup, defence income and military spending were mainly non-transparent, as were defence purchases. But a new far-reaching law was passed in 2024 that excludes all defence matters from public procurement, public accounting, and taxes.

Tunisia has seen democratic backsliding since 2021 which reduced government transparency. Though a strong access to information law exists, defence-related information is often kept confidential. Still, Tunisia has a strong access to information law, with an effective independent oversight body that has helped to implement the law throughout the public sector.

The report offers specific recommendations for each of these five countries to improve access information which broadly fit into these categories:

- Balancing tests: Legal frameworks should require officials to assess the public interest versus potential harm before withholding information.

- Proactive disclosure: Governments should regularly and proactively publish defence budgets, procurement plans, and financial results to enhance accountability.

- Independent oversight: Review bodies should be established to monitor and adjudicate disputes over information access.

- Civil society engagement: Defence planning and policymaking should be open to civil society for broader input and oversight

Notes to editors:

The case studies in Unlocking Access were produced using an updated version of our Government Defence Integrity Index 2020 – the leading global assessment of the governance of and corruption risks in defence sectors. The data was supplemented by interviews with local experts, and the review of policy reports and media investigations.

French and Spanish versions of this press release are available.

Despite widely agreed international standards for access to information in the defence and security sector, transparency remains insufficient to ensure accountability. National security exemptions are frequently applied in vague and undefined ways, limiting the release of precise, timely and detailed information that is crucial for understanding how government is functioning and protecting public interest, especially in areas as fundamental as national security.

Read the launch press release:

Information exchange within government facilitates various types of accountability – from parliamentary scrutiny of executive decisions, to audits of the government’s use of public funds as well as disciplinary sanctions for public officials. More importantly, information disclosure to the public by government bodies also forms the foundation for meaningful citizen engagement and accountability. This is true not just for voting and activism, but for interest in the policies that determine the course of daily life, including whether the security forces are absent, overmilitarised, or well-balanced.

Legitimate national security interests are best safeguarded when the public is well-informed about government activities, including those undertaken to ensure safety and protection. Access to information enables public scrutiny of government action and facilitates public contribution to policymaking and national debate, thus serving as a crucial component of genuine national security, democratic participation, and sound policy formulation. Access to information is also a specific aspect of governance that involves the intentional disclosure of information. These policies require the release of information that is relevant to the public, and is also accessible, accurate and timely.

This report provides an overview of the state of defence transparency and access to information related to defence and security sectors worldwide, drawing on the Government Defence Integrity (GDI) database on institutional integrity and corruption risk. In light

of increasing global military spending (with a new world record of $2.443 trillion recorded in 2023) the overarching focus is on access to defence-related financial information, as transparency and appropriate oversight of defence finances remain critical for public

accountability, among others.

Further, this report also includes a review of global standards for transparency that apply to the defence sector, specifically the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) and the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (or Tshwane Principles). This is coupled with specific exploration of five country cases (Armenia, Guatemala, Malaysia, Niger, and Tunisia) and insights from their legal frameworks and implementation experiences. It concludes with recommendations for good practice to enhance access to information.