If well-balanced, transparency and secrecy can mutually reinforce national security. But in defence and security, transparency trade-offs are often made where they are not needed. How to master this balancing act between national security and oversight? Senior Policy Officer, Emily Wegener, describes how ‘Creating Access: Strengthening And Expanding Information Governance In Defence’, our new quick-start-guide to access to information in defence and security, provides hands-on guidance on this question.

Information is power. Access to information (ATI) legislation and frameworks aim to regulate how this power is distributed. In more technical terms, ATI is known as a specific aspect of governance that involves the intentional disclosure of information. It mandates the proactive release of key information that is relevant to the public, in an accessible, accurate and timely manner. This commonly relates to releasing key information such as budgets, larger purchases, and project evaluations. Through ATI legislation and frameworks, civil society and media can often also request the publication of further, otherwise undisclosed information.

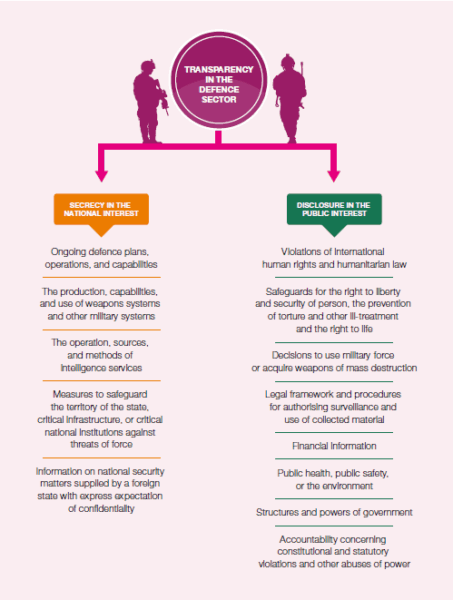

In defence and security, this process is a bit more complex. Requests for data release need to be balanced against potential harm to national security that could be caused by releasing the requested data. This makes transparency in the defence sector a constant balancing act between state secrecy and the public’s right to information. This often complicates effective oversight from media, civil society, and other independent oversight bodies such as parliamentary committees and ombudsmen.

Source: Creating Access: Strengthening And Expanding Information Governance In Defence (2025)

There are legitimate reasons for classifying information: if its release could lead to individual or widespread loss of life, cause serious damage to military capability, impact ongoing investigations or prosecutions, or threaten national security, public health, trade secrets, or economic stability of a State or friendly States. For example, publishing the identities of confidential sources, or details about the vulnerabilities and capabilities of critical infrastructure are obvious cases in which the risk of danger to national security outweighs any potential benefit to the public interest. We hence cannot demand the same degree of openness from defence and security institutions as from other areas of government.

The problem lies not in that information is classified, but that too much information is classified. As our 2020 Governance Defence Integrity Index (GDI) showed, some countries de facto prohibited the release of any kind of defence-related information, whether sensitive or not. In many contexts, the law is vague on what national security actually entails. This lack of definitional precision can lead to overuse of exemption clauses, and put them at risk of being overused to conceal misconduct or mismanagement. Where declassification is an option, data is sometimes released with significant delays and redactions.

This presents a major corruption vulnerability. The less data is available on major activities such as budgets, audits, or project evaluations, the less independent oversight agencies are able to perform their tasks, and the higher the chances are for risks and cases of fraud, corruption, mismanagement and wastage to remain undetected. And the less we know, the less able we are to make well-informed decisions.

How to navigate this balancing act? Well-formulated ATI frameworks require that requests trigger a “public interest test” or “public harms test”. This tasks authorities to balance the potential harm of disclosure against the public interest in disclosure. There should be accessible procedures that allow for substantial review by independent bodies. This is not always common practice though: Of the 86 countries assessed in the GDI 2020, almost half were found to be at high to critical risk of corruption regarding their ATI regimes. Our 2024 report found that out of the five country cases explored in the report, only two had balancing tests in their laws.

A reason for this can be lack of technical expertise. To help with this, TI-DS has developed a quick start guide to ATI in defence. ‘Creating Access’ offers key insights, gap analysis approaches, and tools for immediate application that help assess how to ensure transparency vis-à-vis national security interests. It builds on evidence from our research and the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (The Tshwane Principles). The toolkit provides three tools to generate a snapshot of ATI legal provisions and information availability, along with advocacy opportunities using global standards, multi-stakeholder partnerships, and national collaborative mechanisms: a legal diagnostic tool, an institutional mapping tool, and an action planning tool.

It’s a common phrase that what we don’t know, won’t hurt us. Corruption, however, hurts us most when it stays in the shadows. Getting the balance right between transparency and secrecy is not optional. It is what helps us all work towards the goal of making sound decisions that ultimately strengthen our national and international security and build a stronger defence.