Category: Uncategorised

Europe’s ambitious defence spending plans will only pay off if corruption risks are taken seriously. At our joint roundtable with the Basel Institute on Governance at the Munich Security Conference, industry and political leaders agreed: transparency and strong anti-corruption safeguards are essential if higher spending is to deliver technological innovation, real security gains, and voter trust. It is time to place integrity at the centre of Europe’s defence agenda.

Reflections by Francesca Grandi, PhD (TI-DS), Elizabeth Andersen (Basel Institute on Governance), and Juhani Grossmann (Basel Institute on Governance).

At the 2026 Munich Security Conference, political leaders spoke with urgency about readiness, deterrence, industrial capacity and the need to mobilise unprecedented levels of public and private financing. The tone was sober, the geopolitical risks real, and the commitments delivered with a sense of urgency.

The presence of the defence industry was impossible to miss. Private sector actors were actively engaged in shaping the debate, not only across panels and more informally, but also with a gigantic billboard “We Got This” directly in front of the conference venue.

What we didn’t get was much focus on governance.

With money comes responsibility – and corruption risks

Europe’s defence architecture is being reshaped at historic speed and scale. As we convened our joint roundtable, Get the Balance Right: Capability, Integrity and Effectiveness in Europe’s Emerging Defence Architecture, one theme stood out: this build-up is vital to European security. But it is also a systemic governance test.

The scale of financing under discussion is enormous. Meeting Europe’s defence commitments is estimated to require additional financing of around 2% of EU GDP. At this magnitude, even small governance gaps could translate into billions lost to misallocation, corruption, or fraud. Governance infrastructure must scale in line with spending.

Accelerated procurement, emergency procedures and exceptional budgetary tools are being justified with the urgency of the task, which is understandable. But without enhanced safeguards, they risk:

- heightening fragmentation, overpricing, undue influence, and fiscal distortion;

- weakening transparency and reducing opportunities for civic monitoring; and

- limiting the parliamentary and independent oversight that is necessary to maintain the democratic legitimacy of defence investments.

More spending doesn’t mean more security

The lesson from past crises is clear: spending more does not automatically deliver more security. Defence build-up without governance produces predictable and avoidable risks. Transparency and oversight are not luxuries: they are force multipliers.

This is not a marginal issue. Weak governance undermines defence readiness as surely as underinvestment does. It erodes public trust. It fuels political polarisation. It creates openings for foreign interference and strategic corruption. And it risks turning today’s security investments into tomorrow’s legitimacy crises.

Across panels and side conversations, we repeatedly heard that “the money is there.” What remains contested is how to spend it wisely. How to balance speed with scrutiny? How to ensure that urgent injections of capital do not come at the expense of robust internal controls? How can transparent spending foster flexibility and innovation in defence technology?

Acknowledging the problem is the first step to solving it

At our event in Munich, participants spoke candidly about the tension between scaling production and modernising compliance systems, the political consequences of potential scandals, and the perceived trade-offs between oversight and urgency.

In separate conversations, Ukrainian partners described the dual challenge of mobilising wartime production at the same time as they are strengthening anti-corruption standards, all the while living and working under existential threat.

One structural risk clearly stands out: no single authority is responsible for safeguarding integrity across Europe’s evolving defence ecosystem.

But how do we embed integrity into the EU’s defence architecture?

- First, protect a transparency baseline, even under urgency. Accelerated procedures cannot mean suspended scrutiny. Parliamentary access to information, audit trails, and structured civilian oversight must remain operational. Where secrecy is required, tailored transparency can still reinforce accountability, especially when normal procurement rules are set aside.

- Second, hardwire integrity into new defence financing tools. From day one, EU and national instruments should require machine-readable procurement data, beneficial ownership disclosure, conflict-of-interest controls, and interoperable oversight systems.

- Third, regulate influence where money and policy meet. Public–private cooperation should not blur lines of accountability. As industry access expands, so must lobbying transparency, cooling-off periods, and enforceable revolving-door rules.

- Fourth, align regulation with effectiveness. Smart, predictable standards reduce risk premiums, limit market distortion, and create fair entry points to stimulate innovation.

- Fifth, designate a clear political authority responsible for governance of Europe’s defence architecture. A harmonised anti-corruption framework requires defined leadership; otherwise, oversight will continue to fall between institutions and funding mechanisms.

MSC 2026 demonstrated that Europe is serious about rearmament. The question now is whether it is equally serious about governance.

European citizens will only support sustained defence spending, and the social trade-offs that come with it, if they trust that resources are used strategically and with integrity. That trust can only be secured through robust oversight, transparency, and accountability.

If we are committed to long-term security – beyond the announcements and beyond Munich – then integrity must move from the margins to the centre of the agenda.

The task ahead is clear: get the balance right, and make governance a core pillar of Europe’s emerging defence architecture.

This blog and additional photos are also published on the Basel Institute on Governance’s website.

Get the Balance Right: Capability, Integrity and Effectiveness in Europe’s Emerging Defence Architecture

Join our side event at the Munich Security Conference (MSC) 2026 co‑hosted by Transparency International Defence & Security and the Basel Institute on Governance

EVENT DETAILS

Sunday 15 February 2026 | 13:30–15:00 |Atelier Restaurant, Hotel Bayerischer Hof, Munich

FORMAT

Closed‑door roundtable bringing together policymakers, industry leaders, think tanks, and civil society to discuss how to future‑proof Europe’s multi‑billion‑euro defence investments. Chatham House Rules.

MODERATORS

Dr Francesca Grandi — Director, Transparency International, Defence & Security Programme

Juhani Grossmann — Director, Basel Institute on Governance, Green Corruption Programme

Europe’s defence architecture is being reshaped at unprecedented speed and scale, backed by record spending commitments and new financing tools — making this build‑up not only a capability shift, but a critical governance test.

If governance lags behind, Europe may be rearmed, but not secured. As defence budgets surge, urgency‑driven procurement risks bypassing competition, informal influence channels expand, and oversight mechanisms struggle to keep pace.

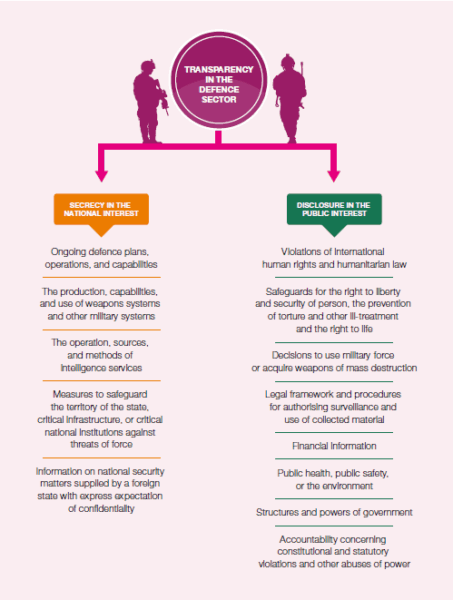

This roundtable focuses on the meaningful role of defence transparency in this transformation. Transparency in defence is not about exposing sensitive operational information; it is about ensuring that decisions, spending, and procurement can be scrutinised, justified, and independently checked so that public resources deliver real security outcomes.

The discussion explores how to anchor new financing mechanisms in strong integrity frameworks, embed oversight into accelerated defence instruments, and ensure that urgency does not trump integrity — so every euro invested strengthens Europe’s collective security.

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY TRANSPARENCY IN DEFENCE?

Transparency in defence is not about exposing sensitive operational details. It is about ensuring, even under accelerated or emergency procedures:

- fair and competitive procurement, responsible export practices, and transparent defence transfer frameworks

- effective parliamentary and independent oversight, meaningful civic and expert participation, and real auditability of defence spending

- responsible public‑private engagement and financing safeguards that prevent undue influence and conflicts of interest

At this year’s Transparency International Movement Summit, the session “A Fragile Peace: Mobilising Our Movement for Accountability and Oversight in Defence and Security Sectors” brought together voices from across the globe to tackle one of the toughest questions in the fight against corruption: how can we ensure accountability in a sector defined by secrecy? Programme Officer Leah Pickering shares her reflections on the session.

Hosted by Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), the session gathered voices from across the TI Movement to explore how chapters are confronting corruption risks in a sector long shrouded in secrecy, where opacity is routinely defended under the guise of national security. What emerged was not just a list of challenges but a shared story of collective courage, a determination to stand together, to keep pushing for transparency and accountability, and to uphold integrity even in the most closed systems.

Facing Secrecy with Courage

Across continents and contexts, from Armenia to Nigeria, and Malaysia to Czechia and Colombia, the discussions underscored a shared reality: while defence and security oversight is crucial for accountable governance, it is still not widely institutionalised. Access to information remains limited, and civil society engagement in this area is only beginning to gain recognition as a valuable contribution rather than an exception.

Sona Ayvazyan of TI Armenia described how access to information is constrained not only by law but also by moral and political sensitivities. Working in a context of conflict and hybrid warfare, she asked a crucial question: how much transparency is safe to demand during times of war?

For Abubakar Jimoh of TI Nigeria (CISLAC), courage has meant confronting power directly. As Nigeria’s defence budget ballooned, CISLAC exposed large-scale mismanagement and illicit financial flows that drained public resources. The backlash was severe, even their Abuja office was attacked, but persistence and coalition-building with media and oversight bodies led to real accountability, including the arrest of senior officials.

In Malaysia, Justin Bryann Jarret explained how secrecy laws make it nearly impossible to access defence information. The Littoral Combat Ship scandal, where billions were spent but no ships delivered, revealed the cost of opacity. By reframing transparency as a tool for efficiency and military effectiveness, TI Malaysia built trust with mid-level defence officials and opened new channels for dialogue.

These stories show that in the face of resistance, courage is often about persistence—finding ways to keep the conversation alive when others try to shut it down.

Building Trust and Reframing Transparency

Speakers agreed that transparency should not be framed as a threat to national security but as its foundation. Marek Chromy of TI Czechia described how their chapter uses data-driven advocacy to show that corruption in procurement weakens, rather than strengthens, defence capabilities. By cooperating with academics and reform-minded officials, they are building credibility and demonstrating that integrity can serve the interests of national defence.

Similarly, Mario Blanco from TI Colombia reflected on the “conflict-corruption nexus,” where corruption fuels violence and violence, in turn, conceals corruption. His chapter’s work developing sector-specific anti-corruption guides and integrity offices shows how collaboration within institutions can turn lessons into reform.

Across diverse contexts, chapters continue to identify constructive partners within government, officials who share a similar aspiration for greater accountability. In this regard, collective courage extends beyond confronting power; it also involves engaging those within institutions who seek to reform them from the inside.

Looking Forward: Turning Courage into Action

The discussion closed with a sense of shared purpose. Chapters may operate in vastly different political and security environments, but the obstacles and the opportunities are strikingly similar. There is growing momentum for a Movement-wide campaign for transparency and integrity in defence and security: a global push that aligns messages, shares expertise, and amplifies each chapter’s impact.

Moving forward, the TI Movement can:

- Coordinate advocacy across chapters to strengthen collective influence.

- Re-examine how the Movement applies frameworks like the Tshwane Principles to ensure they remain relevant across different political and security contexts.

- Build cross-sector partnerships with academia, think tanks, and reform-minded officials.

- Showcase success stories where transparency has improved defence outcomes.

- Continue reframing transparency as a strategic advantage rather than a security risk.

The session, A Fragile Peace, made one thing clear: integrity in defence requires determination, collaboration, and courage. In an age of rising militarisation and shrinking civic space, our collective action is what can turn principles into results.

If well-balanced, transparency and secrecy can mutually reinforce national security. But in defence and security, transparency trade-offs are often made where they are not needed. How to master this balancing act between national security and oversight? Senior Policy Officer, Emily Wegener, describes how ‘Creating Access: Strengthening And Expanding Information Governance In Defence’, our new quick-start-guide to access to information in defence and security, provides hands-on guidance on this question.

Information is power. Access to information (ATI) legislation and frameworks aim to regulate how this power is distributed. In more technical terms, ATI is known as a specific aspect of governance that involves the intentional disclosure of information. It mandates the proactive release of key information that is relevant to the public, in an accessible, accurate and timely manner. This commonly relates to releasing key information such as budgets, larger purchases, and project evaluations. Through ATI legislation and frameworks, civil society and media can often also request the publication of further, otherwise undisclosed information.

In defence and security, this process is a bit more complex. Requests for data release need to be balanced against potential harm to national security that could be caused by releasing the requested data. This makes transparency in the defence sector a constant balancing act between state secrecy and the public’s right to information. This often complicates effective oversight from media, civil society, and other independent oversight bodies such as parliamentary committees and ombudsmen.

Source: Creating Access: Strengthening And Expanding Information Governance In Defence (2025)

There are legitimate reasons for classifying information: if its release could lead to individual or widespread loss of life, cause serious damage to military capability, impact ongoing investigations or prosecutions, or threaten national security, public health, trade secrets, or economic stability of a State or friendly States. For example, publishing the identities of confidential sources, or details about the vulnerabilities and capabilities of critical infrastructure are obvious cases in which the risk of danger to national security outweighs any potential benefit to the public interest. We hence cannot demand the same degree of openness from defence and security institutions as from other areas of government.

The problem lies not in that information is classified, but that too much information is classified. As our 2020 Governance Defence Integrity Index (GDI) showed, some countries de facto prohibited the release of any kind of defence-related information, whether sensitive or not. In many contexts, the law is vague on what national security actually entails. This lack of definitional precision can lead to overuse of exemption clauses, and put them at risk of being overused to conceal misconduct or mismanagement. Where declassification is an option, data is sometimes released with significant delays and redactions.

This presents a major corruption vulnerability. The less data is available on major activities such as budgets, audits, or project evaluations, the less independent oversight agencies are able to perform their tasks, and the higher the chances are for risks and cases of fraud, corruption, mismanagement and wastage to remain undetected. And the less we know, the less able we are to make well-informed decisions.

How to navigate this balancing act? Well-formulated ATI frameworks require that requests trigger a “public interest test” or “public harms test”. This tasks authorities to balance the potential harm of disclosure against the public interest in disclosure. There should be accessible procedures that allow for substantial review by independent bodies. This is not always common practice though: Of the 86 countries assessed in the GDI 2020, almost half were found to be at high to critical risk of corruption regarding their ATI regimes. Our 2024 report found that out of the five country cases explored in the report, only two had balancing tests in their laws.

A reason for this can be lack of technical expertise. To help with this, TI-DS has developed a quick start guide to ATI in defence. ‘Creating Access’ offers key insights, gap analysis approaches, and tools for immediate application that help assess how to ensure transparency vis-à-vis national security interests. It builds on evidence from our research and the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (The Tshwane Principles). The toolkit provides three tools to generate a snapshot of ATI legal provisions and information availability, along with advocacy opportunities using global standards, multi-stakeholder partnerships, and national collaborative mechanisms: a legal diagnostic tool, an institutional mapping tool, and an action planning tool.

It’s a common phrase that what we don’t know, won’t hurt us. Corruption, however, hurts us most when it stays in the shadows. Getting the balance right between transparency and secrecy is not optional. It is what helps us all work towards the goal of making sound decisions that ultimately strengthen our national and international security and build a stronger defence.

By Patrick Kwasi Brobbey, Research Project Manager, Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), Transparency International Defence & Security

I still recall the soft murmur of anticipation in the lecture hall at the London School of Economics during the Black History Month event I co-chaired in October 2023. The discussion that evening centred on the sobering truth that colonialism did not end with independence, as its aftershocks still reverberate through our institutions, shaping who speaks, who is heard, and who is written out. Those words linger with me. Now, as the Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) Research Project Manager, it strikes me how similar hierarchies persist not only through geographic conquest, but also through data, research, and policy frameworks that too often exclude the very voices they claim to represent. As we mark Black History Month in the UK and celebrate resilience, inclusion, and the ongoing struggle for justice, I find myself reflecting on the lessons my work in defence governance holds for confronting these subtle, enduring imbalances of power in knowledge creation.

Introducing the GDI and the Decolonial Perspective

Corruption in defence establishments threatens peace and security by wasting public resources and undermining military capability and the public’s confidence in defence institutions. Yet, owing to the fact that ‘defence exceptionalism’ enables significant secrecy around the workings of defence institutions, it is difficult to monitor and understand defence institutions’ activities to pre-empt and resolve corruption risks. This is where the GDI comes in. It is Transparency International Defence & Security’s flagship global assessment of institutional resilience to corruption in the defence and security sector. It ordinarily evaluates 212 indicators across five risk areas, namely political, financial, personnel, operations, and procurement. Alongside these indicators, the 2025 GDI is piloting two sets of additional indicators, one on the gender dimension of defence sector corruption risks and the other, corruption risks in the protection of civilians and civilian harm mitigation efforts.

Since its inception in 2013 (as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index), the GDI has grown into a respected evidence-based tool used by regional and international organisations, governments, civil society, and the media. Now in its fourth iteration, the 2025 GDI data collection presently covers the sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, and Central and Eastern Europe waves. We are close to completing the sub-Saharan Africa wave comprising 17 countries, including Liberia, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, Madagascar, Uganda, and Burundi. Passed through a decolonial lens, my experiences from this wave mostly inform my reflections here.

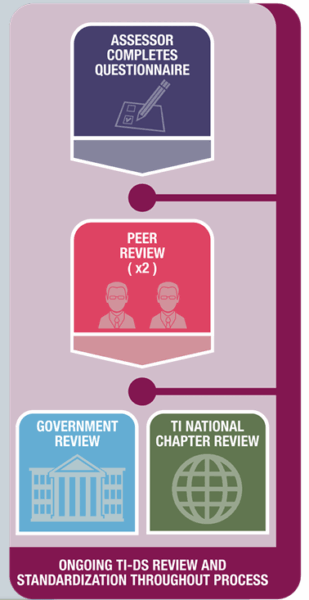

Decolonial scholars remind us that colonialism was not coterminous with independence, since it has persisted through the domination of knowledge, representation, and resources. In this sense, like all large-scale research projects with global scope, the GDI operates within complex asymmetries, particularly disparities in access, visibility, and epistemic authority between the Global North and Global South. To create an index that truly reflects global realities, the GDI not only collects data or produces knowledge globally but does so equitably. This and its benefits can be seen in the GDI research process, whose activities are illustrated in the diagram below.

Source: GDI Methods Paper (2020)

The GDI Country Assessment Process: Building Inclusion into Research

Country Assessment Onset: Transparency International Chapter Consultation

The GDI is primarily produced for Transparency International national chapters – locally established, independent organisations in the Transparency International movement whose purpose is to fight corruption within their respective countries. As such, the sub-Saharan Africa wave began with a March 2024 consultation webinar with Transparency International national chapters in participating countries (e.g., TI Ghana, TI Mozambique, and TI Madagascar) and relevant Transparency International regional advisors.

During this interactive session, we sought their advice on conducting the research in their national and local contexts, including navigating political sensitivities, barriers to access, and potential opportunities and risks to researchers and other stakeholders.

This is more than procedural courtesy. It is epistemic humility. Through the discussions, the chapters and advisors confirm, complement, and challenge the global standards underlying the GDI framework, the GDI research design, its implementation in their countries, and the lenses through which GDI data is interpreted. In decolonial terms, this represents a small but crucial shift from extracting knowledge to co-creating it. As Peace Direct puts it, decolonising research means shifting power to allow for those closest to issues to contribute to the definition of questions and solutions.

During the Assessment: Local Expertise at the Core

Locally based country assessors, often PhD-level researchers with proven expertise on their national defence and security sectors, conduct the GDI country assessments. These experts ground their analysis in the intricacies of domestic policy debates that some external consultants are likely to miss.

Working with them – all of whom have a track record of undertaking field research, publishing in credible international and local outlets, and working with reputable local and international organisations – enables TI-DS to reject the antiquated hierarchy that equates credibility with only proximity to the West. We recognise that local expertise is global expertise, in that experts embedded within systems tend to possess some of the deepest contextual understanding. By prioritising national researchers, the GDI helps to affirm this, echoing the renowned Kenyan author and academic Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o‘s powerful advocacy for hinging the healing of the colonised mind on its realisation that it is the generator of its own knowledge.

Peer Review: Collaboration, Not Correction

Once an assessment is complete, TI-DS coordinates a rigorous peer review. Each draft country assessment is evaluated by two additional country experts. The purpose of this stage is not to ‘correct’ local voices with external ones, but to strengthen the work further by establishing dialogue between different epistemic communities. This exchange deepens the data’s accuracy, illustrating how diversity of perspective enhances research credibility.

Validation: Listening to Governments and Civil Society

The process concludes with consultations with TI national chapters and relevant governments, typically ministries of defence. We invite TI national chapters and ministries of defence to provide evidence-based feedback. For the 2025 GDI sub-Saharan Africa wave, more than half of the national chapters accepted this invitation, notwithstanding that many chapters do not have a defence sector mandate, interest, and/or expertise. Ministries of defence that honoured this invitation include those of Nigeria and Liberia. Rooted in mutual respect, this inclusive final stage not only ensures fairness but also helps foster data quality and the national and local ownership of the findings. This collaborative effort can advance positive change in the defence and security sector’s governance.

Why Decolonising Research Matters

From decolonial theories, we know that knowledge and its production are never neutral. Rather, they reflect the power structures that control them. When research in global policy domains reproduces Eurocentric frameworks by examining phenomena solely through Western epistemologies without national/local considerations, it risks misrepresenting the realities of the societies it assesses. Furthermore, if data collection and analysis are blind to racialised or cultural dynamics of power, the evidence base itself becomes incomplete. This imbalance, which perpetuates injustice and distorts reality, in turn, undermines both the credibility and the uptake of findings among local actors.

The GDI’s iterative consultation model, entailing engagement of national chapters, local experts, and governments, is one way of disrupting this imbalance. It allows for plural epistemologies to coexist within a single global framework. To decolonise, therefore, is not to reject universal standards, but to recognise that universality can only emerge from dialogue among equals, not from prescription by the powerful.

Towards a More Just Knowledge Order

Black History Month reminds us that history is not only what happened but also who gets to tell it. The same is true of data. For too long, the production of knowledge in global governance has mirrored colonial hierarchies: data collected ‘there’ but validated ‘here’. Local expertise is discounted in favour of distant credentials. As researchers and policymakers, we have an obligation to disrupt this pattern.

Building indices like the GDI through a decolonial perspective is not an act of charity or political correctness, but an act of rigour. It makes our findings more representative, our analyses more credible, and our recommendations more actionable. As the globally celebrated Nigerian novelist and essayist Chinua Achebe once asserted, ‘Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.’ The GDI, at its best, seeks to amplify the lions, i.e., the local voices whose perspectives are essential to understanding and reforming defence integrity worldwide.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Map

The colonial cartographers of old believed that to control a space, one must define it. Today, the challenge for global research is to map without domination and to measure without silencing. The process of creating the GDI teaches us that recalibrating uneven racial power dynamics is not peripheral to research quality. Instead, it is its foundation. When those who live the realities of governance and security are full partners in collecting and interpreting data, the result is not only more just but also more accurate and credible. As we mark Black History Month, may we remember that the fight against corruption and the fight against epistemic injustice are, ultimately, the same fight.

Civil war has been raging in Sudan for soon two years with no end in sight. Its violence and destruction have caused a “humanitarian catastrophe”. Yet, as the conflict remains at the margins of media and public attention, so does one of its main drivers: corruption.

Weak defence governance and failed security sector reforms have played an important role in driving the conflict. Over the last six years, Sudan has experienced high levels of political instability, writes Emily Wegener.

Whether as a driver of the protests in 2018-2019 that forced President Omar al-Bashir out of power, or a as contributing factor to the October 2021 military coup staged by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that halted the democratic transition process, corruption continuously contributed to this volatility. Regimes fell, but the power structures and the corruption networks in and around the military and security forces survived. These networks then fuelled tensions between the SAF and RSF, which reached their breaking point in April 2023 with the outbreak of armed conflict between the two groups.

From the onset of the conflict, corruption has driven the violence. Failure to agree on a way forward in the country’s security sector reform (SSR) – the process of improving a country’s police, military and related institutions to ensure they are effective, accountable and respect human rights – is widely seen as one of the key reasons for why the democratic transition failed. Placing the RSF under civilian control and enhancing democratic scrutiny of the SAF were two of the most contentious questions in the SSR process.

But what made improving the oversight and accountability of these groups so contentious? Our 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) assessed the corruption risk as critical throughout Sudan’s defence institutions, concluding that “corruption is widespread in the sector and there are virtually no anti-corruption mechanisms”. Civilian democratic control and external oversight of defence institutions were also found to be non-existent.

An absence of accountability enabled both the SAF and the RSF to repurpose the state’s defence and security institutions to enrich high-ranking security officials and create an economy dominated by military interests. Companies owned by SAF officials have long controlled lucrative private sectors, from telecommunications to meat processing, to the detriment of public investment and sustainable economic growth. Meanwhile, the RSF controls most of the country’s gold trade – a significant income stream, considering that Sudan was the third-largest gold-producer on the continent in 2023. By the time the war broke out, the RSF owned around 50 companies, acquired largely by reinvesting the profits from gold trade into other industries. Transition to civilian rule would have meant placing the SAF under civilian oversight; for the RSF, integration into the army. When the RSF was not ready to give up its advantages, or accept this level of accountability, it declared war.

Why we produced ‘Chaos Unchained’

In February 2025, nearly two years the outbreak of the war, Sudan is facing starvation and the world’s largest displacement crisis. An estimated 30% of the population, over 11 million people, have been forced to leave their homes. According to the UN Secretary General’s latest report, over 25 million people live in food insecurity, including over 750,000 people living in conditions comparable to famine, as defined by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). Both sides, and the RSF in particular, are reported to have perpetrated ethnic cleansing and sexual violence.

Yet, the attention paid to the conflict is scarce. Sudan rarely makes the headlines. Across the international community, the focus is elsewhere. To shed light on this ‘forgotten conflict’ and its drivers, we have produced a 10-minute video looking at the origins of Sudan’s turmoil. Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan examines how corruption, kleptocratic plunder of the country’s resources and lax enforcement of arms embargoes have contributed to the ongoing conflict and the humanitarian catastrophe that comes with it.

Possible solutions

Governments and private actors can take steps to reduce the role of corruption in prolonging the fighting, and to limit the chance of relapse after a political solution is negotiated.

At international level, the UN, the EU and their Member States can:

- Recognise the links between corruption in the defence and security sector and the violence and elevate the importance of addressing corruption in the conflict resolution agenda. A strong precedent is the UN Security Council Resolution 2731/2024 on the situation in South Sudan, where the Council recognises that “intercommunal violence in South Sudan is politically and economically linked to national-level violence and corruption”, and stresses the need of effective anti-corruption structures to ensure and finance the political transition and humanitarian needs of the population.

- Explore the links between arms diversion and corruption, and the resulting circumvention of UN arms embargo and human rights abuses in the Darfur region. Existing mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Sudan and the Security Council’s Panel of Experts can contribute to improving the evidence base on the role of corruption, especially in the defence and security sectors, in fuelling the war and humanitarian crisis.

- Prioritise strengthening the rule of law and anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding. Placing the SAF and the RSF and their economic assets and activities under civilian oversight is a key step toward transparent and accountable defence and security forces. A long-term, transformative, and inclusive SSR process will be the most necessary but also the most contentious element of any negotiated solution to the conflict in Sudan. Additionally, any peacekeeping or peacebuilding interventions will need to firmly prioritise anti-corruption as a conflict prevention measure.

At national level, the governments of arms exporting countries can:

- Strengthen arms export policies and implementation guidelines. Foreign-made weapons and military equipment are being diverted into Darfur despite a long-standing UN Security Council arms embargo. Arms exporting countries can use our GDI to better assess the risk of corruption in defence institutions. Robust corruption risk assessments can help to curb diversion risks in arms sales to Sudan and the regional partners of the SAF and the RSF.

- Better regulate defence offsets. In connection with major arms sales, defence companies often negotiate lucrative offset packages with even less transparency than the arms sales. Our research has shown that defence company offsets can contribute to fuelling conflict dynamics, including in countries like Sudan by supporting industries in the UAE that help finance Sudanese armed actors. Enhancing internal and external transparency and oversight around these deals can mitigate risks of contributing to natural resource laundering for armed groups and fuelling conflict dynamics such as the one in Sudan.

Sudan shows that fighting corruption is not separate from discussions on ceasefires, political negotiations and peace processes. Integrating anti-corruption measures and fostering transparency and accountability in Sudan’s defence and security sector is key to the long-term success of any negotiated political solution.

You can watch Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan here.

Register here to join our webinar on Thursday, 6 February, in which we discuss the root causes of the conflict and pathways to peace with an expert panel.

Two years have passed since Burkina Faso witnessed its second coup within a year, on September 30, 2022, plunging the troubled nation into deeper instability and uncertainty.

Since these pivotal events, it is important to examine some of the governance factors that led to them and the profound impact they have had on the country’s security and its people. The coups in Burkina Faso are not isolated incidents but symptoms of long-standing issues in the nation’s defense and security sectors, made worse by persistent corruption and weak governance, write Michael Ofori-Mensah and Harvey Gavin.

The first coup in January 2022, led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, was partly fuelled by the Burkinabè government’s inability to contain the growing jihadist insurgency that has plagued the region as well as weak civilian oversight of the military. Despite international support and initiatives aimed at stabilising the country, the government’s efforts faltered, leaving the population increasingly vulnerable to extremist violence. This continued failure eroded public trust in the government’s leadership. After a series of anti-government protests, the country’s democratically elected president, Roch Kaboré, was ousted by members of the Burkina Faso Armed Forces on January 23.

Just months later, on September 30, 2022, a second coup, led by Captain Ibrahim Traoré and comprised of other members of the armed forces frustrated with the lack of progress in improving the security situation, overthrew the leaders of the first. But instead of paving the way for stability, this second coup further destabilised the country, deepening the security crisis and undermining any prospects for effective governance. Figures from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project show 1,985 civilians were killed in Burkina Faso during the two years leading up to the second coup (from September 30, 2020, to September 30, 2022). Despite the leaders of both coups claiming they would improve the security situation, 4,843 civilians were killed in the two years after September 30, 2022.

At the heart of Burkina Faso’s instability lies a deep-seated problem of weak governance and pervasive corruption within the defence and security sectors. Our 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) found that the country faces considerable corruption risk across its defence institutions, with little to no transparency or controls across finances and procurement. These issues significantly contributed to weakening the resilience of the military and its ability to effectively address the jihadist threat.

Corruption within the country’s defence and security sector has diverted resources away from critical security needs, weakening the military’s operational capabilities while eroding the trust between the armed forces and the civilian government. This was highlighted in 2021 when in June jihadists killed more than 100 people in Solhan, a village in the north of the country. In November of the same year a further 49 police officers and four civilians were killed near Inata, in the same region. A memo from security forces in the area warned their superiors that they had run out of food and had been forced to commandeer livestock from citizens. The lack of safeguards against corruption in defence and security institutions has played a major role in the deteriorating security situation, creating fertile ground for insurgent groups to exploit and thrive.

The ongoing jihadist insurgency has had devastating effects on Burkina Faso’s security landscape and its people. Attacks have become more frequent and brutal, targeting both military personnel and civilians, with more than 6,000 people killed – including around 1,000 civilians – between January and August this year. The pervasive insecurity has created a climate of fear and instability, with entire communities displaced.

The inability of successive governments to effectively address the insurgency has only exacerbated the situation. Each failed attempt to quell the violence has diminished public confidence in the government and increased public frustration. This frustration has, in turn, provided fertile ground for military coups, which, rather than resolving the underlying issues, have led to further instability.

New research from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies highlights vividly the scale of this instability. The Sahel region accounts for more than half of all annual reported fatalities (11,200) involving militant Islamist groups in Africa. Burkina Faso bears the majority of this violence (48 percent) and fatalities (62 percent) linked to militant Islamist groups in the Sahelian theater.

Note: Compiled by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, each map shows violent events involving the listed groups for a year ending June 30. Group designations are intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered official. Due to the fluid nature of many groups, affiliations may change.

Sources: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); Centro Para Democracia e Direitos Humanos; Hiraal Institute; HumAngle; International Crisis Group; Institute for Security Studies; MENASTREAM; the Washington Institute; and the United Nations.

Beyond the political and security implications, the escalating jihadist insurgency has had a profound impact on human security in Burkina Faso. The civilian population bears the brunt of the violence, facing daily threats to their lives and livelihoods. Families have been torn apart, and communities have been shattered by the constant threat of violence and displacement.

Had there been greater resilience and integrity within Burkina Faso’s defence and security institutions, the trajectory of the country’s security situation might have been different. Strong, accountable institutions are essential for maintaining internal stability and effectively countering security threats. They build public trust, ensure the proper allocation of resources and foster cooperation between military leadership and the population they are entrusted to protect.

Two years since the September 2022 coup, it is imperative for regional bodies like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the international community to renew their commitment to supporting Burkina Faso. While international forces are no longer in the country,

The past two years have underscored the urgent need for comprehensive reforms in Burkina Faso’s defence and security sectors. The recurring coups, driven by the government’s inability to manage the jihadist insurgency, have only deepened the nation’s challenges, leading to greater instability and suffering for its people.

Burkina Faso stands at a crossroads, grappling with the fallout of a series of coups which have been fuelled by a lack of integrity, accountability and transparency in its defence and security sector. The withdrawal of international forces, including UN personnel, has left civilians vulnerable to escalating jihadist violence, as evidenced by recent reports documenting significant civilian casualties. Meanwhile, the Burkinabè armed forces have also suffered heavy losses.

The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States, following Burkina Faso’s exit from ECOWAS, complicates the prospects for meaningful dialogue and reform. Amidst the global focus on conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza and Lebanon, the profound human tragedy unfolding in Burkina Faso and the wider Sahel region must not be overlooked. It is imperative for ECOWAS and the African Union to take decisive action, with the support of the international community, to strengthen defence governance as part of broader reforms. Cooperation, not competition, is key to addressing the corruption and insecurity issues the region faces. Civil society should have guaranteed freedom of expression, and space, to participate in the peacebuilding and conflict prevention process. The Burkinabè government needs to provide mechanisms for this participation, as well as broaden public debate on defence issues and policies.

Overall, commitment to civilian democratic oversight of the armed forces is essential for building a resilient defence sector and ensuring the protection of the Burkinabè people.

As world leaders convene in Washington DC for the 2024 NATO summit, Ara Marcen Naval highlights the need to address and prevent corruption in military spending.

As global insecurity rises, so does militarisation and defence spending. The latest data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) shows world military expenditure rose for the ninth consecutive year to an all-time high of $2.443 trillion in 2023. This represents an increase of 6.8 per cent in real terms from 2022, which is the steepest year-on-year increase since 2009. This sharp rise demands our attention and underscores the urgent need for greater transparency in military spending.

Transparency International Defence & Security has long sounded the alarm on corruption – a hidden threat in times of rising military expenditure.

Corruption in the defence sector is multifaceted. While bribery is the most recognised form, corruption also includes conflicts of interest, embezzlement, nepotism, sextortion, and undue influence. This pervasive issue thrives in environments characterised by secrecy and wealth – factors that are especially prevalent in the defence and security sector. Often deemed too complex and sensitive for meaningful external scrutiny, this sector is fertile ground for corruption when oversight is inadequate.

The rise in defence spending is linked with increasing corruption risks. Increased spending must be accompanied by vigilant attention to corruption risk. There is a strong indication that the relationship between defence spending and corruption is cyclical. In countries experiencing state capture – where private interests corrupt a country’s decision-making to benefit themselves, rather than the public – elites are more likely to prioritise military spending, further perpetuating corruption.

Many defence institutions worldwide are ill-equipped to manage the higher corruption risks that militarisation brings. Transparency International Defence and Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), which assesses countries on the strength of their safeguards against defence and security corruption, shows one-third of the world’s top 40 highest military spenders face high to critical corruption risks in their defence sectors. Even if some high spenders may have stronger domestic controls, they often export arms to countries facing much greater corruption risks.

Evidence shows that countries spending more on defence as a percentage of GDP tend to score lower in the GDI, indicating higher vulnerability to corruption. The 15 countries with the biggest military spending increases between 2021 and 2023 fall into c moderate to high corruption risk categories.

As international insecurity rises, so does global defence spending. However, the hidden cost of this escalation is the proliferation of corruption within the defence sector. When defence spending rises in countries where corruption safeguards are not prioritised, the issue becomes more serious. Corruption in the defence sector undermines peace and security by diverting critical resources and eroding public trust.

To manage the corruption risks associated with defence spending, NATO and its allies should:

- Ensure comprehensive transparency and oversight of defence budgets, allowing the public to have a clear picture of spending plans.

- Implement controls to reduce the risk of funds being lost to corruption as budgets are spent, such as granting parliaments, or a parliamentary defence committee, extensive powers to scrutinise spending and publishing the approved budget in an easy-to-understand form.

- Integrate anti-corruption measures into arms export controls to prevent exporting arms to countries unable to manage corruption risks.

- Utilise good governance and transparency as a tool for deterrence against foreign or domestic threats.

Only by addressing and preventing corruption can we ensure that defence and security sectors genuinely uphold national and human security, rather than exacerbating insecurity and putting populations at further risk of harm.

About the Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI)

The GDI measures institutional resilience to corruption by focusing on policymaking and public sector governance in national defence institutions. The Index is organized into five main risk areas: policymaking and political affairs, finances, personnel management, military operations, and procurement. Each indicator is scored based on five levels from 0-100, and scores are aggregated to determine the overall corruption risk level, ranging from A to F.

Header image: Dragoș Asaftei – stock.adobe.com

Corruption has serious effects on development, human rights, peace and security. But too often it is viewed as a bureaucratic crime and its real-life impact on people is still overlooked and underestimated.

International processes have the power to change this. The 2024 Summit of the Future in September can be a “roadmap to getting things right” – but so far, the agenda includes very little about corruption. On the margins of the UN Civil Society Conference in Nairobi in May, our webinar aimed to put it on the map.

In this blog, Emily Wegener, our Evidence and Advocacy Officer, summarises the key takeaways from the webinar.

Betrayed by the Guardians: The Human Toll of Corruption in Defence and Security from Transparency International UK on Vimeo.

When we think about corruption, our first thought is often about the culprits: politicians stealing large amounts of public money, businesspeople bribing officials to get their way, officials handing out contracts to friends or family. Public discussions as well as policy solutions often centre around political ramifications and changes to technical processes.

As a result, we often think of corruption as a purely bureaucratic crime. The human suffering that it inflicts on populations across the world every day remains silent. To give it a voice, Transparency International Defence & Security published its latest briefing, Betrayed by the Guardians: The Human Toll of Corruption in Defence and Security. Sharing five personal experiences of corruption in defence and security from around the globe, drawn from first-hand conversations with those willing to give testomony, and from investigations conducted by media and international organisations, it sheds light on the dramatic and direct effects on peace, security, and stability caused by corruption in the notoriously secretive and closed off defence and security sector.

The panellists at our launch event on May 8 gave testimony to what happens when the very institutions responsible for the protection of civilians fail to fulfil their mandate, act with impunity, and break public trust. Here is what they said:

- Peggy Chukwuemeka, Executive Director of the Parent-Child Intervention in Nigeria, shared how her home region in Southeast Nigeria went from being one of the most peaceful parts of the country to one of the most unsafe. She told how violence by non-state armed groups led to the deployment of state security forces to the region. Random and unjustified checks on civilians, which seemed more like a demonstration of power, and extortion of bribes by security forces occurred frequently. But those affected were often scared to speak up or lacked safe reporting mechanisms. Peggy explained how the violence also had gendered dimensions, due to lack of female security personnel to make women in the communities feel safer, and higher vulnerability of female community members to violence and extortion.

- Sayed Ikram Afzali, Chief Executive Officer of Integrity Watch, Transparency International’s Chapter in Afghanistan, shared his experiences from participating in the country’s National Procurement Commission. He heard reports that the soldiers were receiving much less food than they were supposed due to ongoing corruption in the military’s procurement system. The president of the commission ordered a committee to be formed to investigate this claim, but even the formation of this committee, or any other kind of independent oversight of the security sector, was blocked by corrupt political networks. Surveys by Integrity Watch showed how examples like this inflicted high and ever-increasing bribe payments on an already impoverished population. Ultimately, pervasive and little-addressed corruption in the Afghan National Security Forces enabled the complete breakdown of their ability to function, which made the rapid Taliban takeover in 2021 possible.

- Jacob Tetteh Ahuno, Programmes Officer at Ghana Integrity Initiative, Transparency International’s chapter in Ghana, shared how citizens in the border regions observed vehicles carrying goods in and out of the country via unapproved routes. Bribery of security guards stationed along these roads is one of the reasons why some of these vehicles were able to smuggle weapons into the country, which are then used by non-state armed groups to terrorise local communities.

- Najla Dowson-Zeidan, our former Advocacy and Engagement Manager and lead author of Betrayed by the Guardians, explained how, while writing the briefing, she found the common theme in the stories to be those with power abusing their power at the expense of vulnerable people, for their own profit. The title of the publication reflected how we rely on defence and security forces to protect our lives and security, so when corruption occurs in these sectors leading to people’s lives becoming endangered and unsafe, these forces have betrayed their mandate.

What these stories show us is that the consequences of corruption go far beyond the economic and the political. It is a social issue, a development issue, and a human rights issue. But what can be done to improve the situation? And how can upcoming ‘big moments’ at the international level, such as the Summit of the Future and its key outcome, the Pact for the Future, be a pathway to much-needed systemic change?

The speakers and audience at our webinar made several suggestions for what UN Member States can do this September at the Summit of the Future to accelerate systemic change:

- Acknowledge the devastating impact that corruption, as a root cause and consequence of conflict, has on human lives and livelihoods, and the pressing need to holistically address it across all sectors.

- Include clear commitments on addressing corruption in the Pact for the Future that include clear targets and objectives, and resourcing to achieve this.

- Learn from cases like Afghanistan by acknowledging corruption as a national security priority, especially in fragile contexts, and responding to it through a whole-of-society approach with a strong and supported civil society.

- Bridge the gaps between different policy communities so that corruption is no longer seen as separate from development, peace and security, and these communities come closer together to work on tackling these issues.

- Increase the transparency of defence budgets and allow for more independent oversight to enable civil society and the media to tackle corruption and increase accountability for human rights abuses of defence and security forces.

The stories shared in our briefing and during the webinar paint a clear picture of the devastation and suffering caused by corruption. The time for change is now: The Summit of the Future offers a once-in-a-decade opportunity to bring forward innovative, ambitious and impactful systemic change to end corruption. Tackling it is a core part of our journey to sustainable peace and development. Our future is safer without corruption – let’s make a Pact that saves lives.

Josie Stewart, head of Transparency International Defence & Security, reflects on a busy week at the Tenth session of the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption in Atlanta.

The 10th session of the Conference of the States Parties (CoSP) to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) showed two things very clearly: the fight against corruption is receiving more attention than ever – but that attention has not yet translated into enough action, especially in defence and security.

Let’s start with the good news. The past week, I and more than 1,000 others spent six days running around a bustling conference centre in Atlanta, USA. Countries sent large delegations, and negotiations continued late into the nights. Unlike previous CoSPs, the 10th session saw significant attendance from global civil society, ensuring transparency and meaningful engagement.

And there is more good news. Thanks in part to the host country’s leadership, we saw corruption recognised as the security threat that it is. During the two days of opening remarks from participants, speaker after speaker acknowledged the impact that corruption has on stability, peace, and security, and I also had the pleasure of taking part in a panel discussion on this topic. We hope to see this sentiment reflected in the flagship resolution of the CoSP, the Atlanta Declaration, once it is published.

But here come the caveats. We all spent a lot of time admiring the problem, rehashing time and again the fact that corruption is bad, and there was a lot of preaching to the choir. Even in the many policy discussions and panel events that took place alongside the formal negotiations, where there was markedly little challenge, new thinking that could really push the anti-corruption agenda forward, or focus on concrete actions that could and should be advanced.

Without concrete actions, acknowledgement of corruption as a security threat remains just the first step to addressing it. And at CoSP10, the international anti-corruption community was a long way short of real action when it comes to addressing corruption in defence and security.

I’ve seen the effects of this first hand – and they are devastating.

During my time leading the UK Government’s anti-corruption agenda in Afghanistan, I witnessed the devastating effects of neglecting corruption. The failure to prioritize combating corruption led to the disintegration of the Afghan national defence forces as the Taliban advanced. In South Sudan, while working on defence governance reform, I saw how accountability and transparency were sidelined, allowing corruption in the military to fester.

Corruption is about money and power, and there’s an abundance of both in defence and security. Yet anti-corruption policy communities rarely have meaningful engagement with national security and defence policy communities. Until this week, there was no discussion about defence and security at the UNCAC CoSP

So now the words are there at least, what needs to be done?

We’re challenging states to examine how well their anti-corruption efforts are identifying and taking on the tough political choices that are needed in order to address corruption as a security threat, and we’re challenging states to focus on addressing corruption within their defence and security sectors as a critical aspect of their wider anti-corruption agendas. We want an agreed resolution on this in two years’ time, when the next UNCAC CoSP takes place.

We need to call corruption in defence and security by its name: a threat to human, national and international security. These words are now being spoken by many, but getting from words to actions, from acknowledgements to clear commitments, is the next challenge, and it is a challenge that we are committed to meet head on.

Integrity is the cornerstone of peace and security, writes Yi Kang Choo. Amid the delicate security challenges currently facing Taiwan, we visited Taipei to share a roadmap for upholding integrity in military operations and procurement.

Hailed as the ‘integrity experts’ by Taiwanese media, a Transparency International Defence and Security (TI-DS) delegation led by Head of Advocacy Ara Marcen Naval was recently invited to deliver the keynote speech at the 2023 International Military Integrity Academic Forum in Taiwan. A packed week in Taipei, the capital, saw the team encourage and support countries in the Asia Pacific region to strategically address corruption risks in their national defence and security sectors.

Above: Leading the TI-DS delegation is Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy (left centre), along with Najla Dowson-Zeidan, Advocacy & Engagement Manager (3rd from the left), Yi Kang Choo, Programme Officer (1st from the left), and Prof. Byung-Ook Choi, Transparency International South Korea (4th from the left).

Corruption represents a critical national security threat in this geo-politically sensitive region

The audience included directors from the Ministry of National Defence Procurement Office, Department of Resource Planning, Division of Defence Strategy and Resources, as well as the Ministry of Justice and the Agency Against Corruption. Companies within the defence industry were invited on the second day of the Forum.

Above: Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy of TI-DS delivering keynote speech to attendees of the forum

Our delegation was hosted by Po Horng-Huei, Vice Minister of Defence (Policy) of Taiwan. We were joined by the Integrity Defence Committee in Transparency International Korea and members of Transparency International Taiwan.

Regional trends and corruption risks

As shown in our GDI index, while Taiwan generally scores highly on institutional resilience to corruption in defence, key defence sector corruption risks in Taiwan and across the Asia Pacific region reside within military operations. Corruption in operations undermines the power of deterrence.

When defence institutions lack integrity, deterrence strategies lose credibility. When neighbouring countries perceive a nation’s military as corrupt or compromised, they might view deterrence signals as less credible, potentially emboldening them to take more aggressive actions. Given Taiwan’s security ties to the stability of the region, any perception of corruption within Taiwan’s defence sector could potentially be exploited by adversaries seeking to undermine the credibility of its defence and weaken Taiwan’s position in the region. Moreover, such perception of corruption could incentivise aggressive behaviour by others, potentially leading to territorial expansion or military provocations, with the potential to destabilise the entire region.

Defence offsets: the mutual responsibility of defence companies and governments to operate with integrity

Countries across the world are developing and implementing new policies and strategies to strengthen their national defence manufacturing capabilities in response to elevated geo-political conflict, resource competition, and changing alliances.

Rather than focusing on boosting their defence manufacturing through direct grants and contracts with local defence companies, many countries are pursuing defence offsets – a form of industrial cooperation which involves foreign defence company investments in local defence or other economic sectors in exchange for securing arms deals with buying governments. The total value of defence offsets in Asia is expected to reach US$88 billion by 2025.

Countries in Asia and Oceania, both with developed and underdeveloped defence industries, are adopting defence offsets for various purposes. For example, Taiwan seeks to introduce high-tech industries, encouraging foreign investment, promoting exports, and improving industrial structure. Moreover, the facilitating role of industrial cooperation to the remarkable success in the semiconductor industry is widely acknowledged among policy makers in Taiwan.

However, this trend is not without its corruption risks.

Former government officials from across the region have highlighted “how offsets are susceptible to corruption within a sector where bribes can represent nearly twice the contract value of procurements in any other sector.” In India, the government has been investigating at least three corruption cases.

Some defence industry representatives have even cancelled contracts due to corruption concerns in offset related transactions. This form of corruption has hurt countries’ abilities to perform critical military missions, slowed growth in local defence industries, and eroded trust in government integrity.

Against this backdrop, the Transparency International Defence and Security delegation urged companies to publicly acknowledge the corruption risks associated with offset contracting and ensure that all offset partners and projects are subject to enhanced due diligence procedures. Defence companies should be transparent about any involvement in offset projects worldwide. Moreover, government officials and departments dealing with offset projects should enhance their oversight of key risk areas, including the use of wide-ranging multipliers to assess the value of proposed or completed offset projects, and the ability for defence companies to provide cash payments or working capital to any type of local company.

Above: Prof. Byung-Ook Choi, a member of the Integrity Defence Committee in Transparency International Korea speaking on stage, sharing his concerns and recommendations on offset policies to reduce corruption risks.

Another key area of risk within the region is corruption in the arms trade and defence procurement.

Global military expenditure in 2022 was $2.2 trillion – 3.7 per cent more than the previous year. China’s military spending rose last year for the 28th consecutive year, to reach $292 billion. Military spending in Taiwan is also rising, driven by concerns about regional security.

These increases in spending on defence, alongside the scale of corruption risk in the defence sectors of arms exporting and importing countries, brings increased risk of distorted defence spending priorities and military acquisitions, imbalances in the distribution of military capabilities, corruption-enabled arms diversion, and diminished military capability. Corruption in defence procurement can undermine the quality and reliability of military equipment and infrastructure, jeopardising the safety and operational effectiveness of armed forces during potentially critical situations.

To manage these risks, increases in defence spending must be accompanied by corresponding improvements in transparency and defence governance.

Above: Hybrid Regional Meeting between TI-DS with TI Chapter Representatives from Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Looking ahead

Our visit to Taiwan exposed us to the dedicated efforts of the Taiwanese government to uphold transparency and integrity standards in their defence and security sectors. However, as is often the case in countries with high military expenditures and national security pressures, it remains possible for the full extent of the risk of corruption, or the perception thereof, to be overlooked. This risk has the potential to significantly impact a nation’s defence readiness and deterrence, Taiwan included.

Therefore, the need for continuous improvement is paramount. Addressing corruption risks within the defence sector is not an ethical obligation; it is a strategic imperative for Taiwan’s security, reputation, and stability. By actively working to eliminate corruption risks, Taiwan can continue to bolster its defence capabilities and contribute to regional stability, whilst at the same time setting an example for other countries in the region and beyond.

Proactive regional cooperation to promote defence integrity

In the margins of the Integrity Forum, we took the opportunity to convene and strengthen our alliances for more robust regional and global advocacy with Transparency International Chapter representatives in the region including South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Taiwan.

By aligning regional priorities and interests with our chapter colleagues, we eagerly anticipate more countries stepping up as champions against corruption within their national defence sectors, emulating Taiwan’s example and igniting a contagious movement of heightened integrity and security throughout the region. We’ll continue to emphasise that civil society organisations like Transparency International Defence and Security are allies in this ongoing, challenging, and profoundly important struggle to instil integrity in defence and security and create a safer world for all.

Yi Kang Choo is Programme Officer at Transparency International Defence and Security.

Responding to the reported coup in Gabon, Josie Stewart, Director of Transparency International Defence and Security, said:

This is the eighth coup in Central and West Africa in the last three years.

Corruption in the security sector has long fuelled insecurity across the region.

It has been inadequately addressed through security sector reform.

The consequences for the social contract and governance are severe.

press@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

Out of hours – Weekends; Weekdays (UK 17.30-21.30): +44 (0)79 6456 0340