With security threatened by increasingly belligerent armed actors and a hastened drawdown of international troops due to COVID-19, Iraq cannot afford to leave its defence institutions open to corruption.

By Benedicte Aboul-Nasr

Since October 2019, Iraq has seen tensions in its political sphere, including public protests, declining oil prices, increasing risks of proxy war between the US and Iran, and the resurgence of violent armed groups; the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated an already precarious security situation. After six months without a government, Iraq’s parliament appointed Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi in May 2020, and granted his full cabinet confidence in June. To respond to the state’s most urgent priorities, the incoming government and its international partners should urgently consider addressing risks of corruption and human rights violations, in particular in the defence sector, to guarantee that the defence forces have the capacity, resources, and popular backing, to respond to priorities.

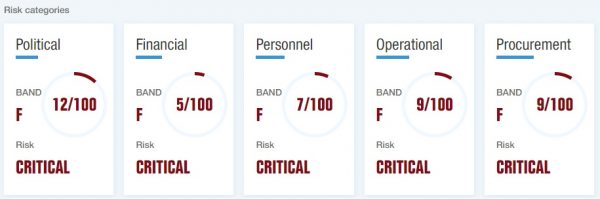

In research published this week, Transparency International – Defence & Security has found Iraq’s defence sector to be at critical risk of corruption, and lacking anti-corruption and transparency mechanisms. In fact, our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) indicates that Iraq is particularly vulnerable to risks relating to finances and personnel, and does not fare much better in the areas of political, operational, and procurement corruption risks, with an overall score of 9/100 on the Index. Corruption has been linked to the erosion of institutions and of trust, and is one of the main grievances driving the protests that broke out last October. As critical as these results are, they offer the new government a blank slate to meaningfully reform the defence sector from the ground up; this will be imperative to secure longer-term security for the country.

COVID-19 has added another threat; the crisis has severely affected Iraqi citizens, as security forces enforce curfews against a backdrop of unrest and accusations of forces deliberately firing on protesters, killing over 600, injuring thousands, and recent reports of ill-treatment and torture of anti-government protesters. It is also likely to disproportionately affect displaced populations, more vulnerable to the pandemic following years of conflict and displacement, with more poorly resourced accommodation, protection, and health systems. Crucially, the pandemic has also generated additional security challenges, as the government and defence institutions redirect resources towards its pandemic response, while simultaneously countering the apparent resurgence of extremist groups. Indeed, Iraq is already facing the resurgence of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which are seeking to exploit the governance vacuum and the pandemic to resurface.

Governments around the globe have rapidly shifted their own priorities in response to COVID-19. Within weeks of the outbreak, France, Canada, the United States and several European countries in the global coalition against ISIL announced temporary withdrawals of their troops from Iraq and from NATO Mission – Iraq. Meanwhile, Operation Inherent Resolve announced that it had stopped training Iraqi security forces, as the Iraqi military also suspended its trainings to reduce the spread of the virus. Against this backdrop, ISIL has actively called for its members to ‘act’, encouraging supporters to ‘exploit disorder’ and is increasing the pace and violence of attacks, taking advantage of the drawdown of international troops.

Countering corruption risks in defence must therefore become a priority. Doing so would limit the risks of abuses of civilian populations, illegal trade of cultural property, of theft or diversion of already limited resources, and would ensure that Iraq’s defence institutions can respond to the multiple challenges it faces. Iraq has seen the consequences of a poorly governed and corrupt defence sector: the military cannot afford vulnerabilities akin to those that enabled the rise of ISIL in 2014. At the time, corruption fuelled problems which left troops hollowed out and outnumbered, such as equipment theft and ‘ghost soldiers’ – members of the military whose names were registered and salaries disbursed, without being present in military ranks. ISIL actively used these issues as recruitment tools in its propaganda, and militants developed government functions in areas where relations with government had deteriorated for years. The group benefitted more concretely from the erosion of security services, where corruption had thrived, to take over swathes of territory, leading to the prolongation of the conflict. Despite the military defeat of the group in 2018, these vulnerabilities remain and risk weakening the Iraqi armed forces when they are most needed.

Iraq’s defence institutions and oversight are severely lacking, and do not fulfil basic requirements of anti-corruption and transparency. Yet they can no longer afford a weak stance on corruption, nor on human rights. To avoid exploitation of existing vulnerabilities and erosion of the defence and security forces similar to those that led to Mosul’s fall in 2014, the government must turn its attention to defence governance, and tackle existing vulnerabilities such as those highlighted by the GDI. The incoming government is in a unique position to do so, and has already pledged to investigate the allegations of torture disclosed by the UN. The government could also take concrete steps and measures to strengthen integrity and accountability within the armed forces. In addition, both the new Defence Minister, Juma Inad, and Interior Minister, Osman Ghanimi, have extensive and highly respected military backgrounds and an in depth understanding of Iraq’s security challenges which could support reform of the defence and security sectors.

International partners have a critical role to play and should actively promote instilling anti-corruption systems into longer-term institution building and reconstruction efforts. For instance, international partners should prioritise including anti-corruption and integrity building within training courses and partnerships with the armed forces. They could also, as a means of supporting longer term development of defence institutions, support the development of accountability structures, such as streamlining a code of conduct for all military forces, developing and implementing mechanisms to allow whistle-blowing and whistle-blower protections within the armed forces, and setting up clear systems for investigations of allegations of abuse.

Armed groups in the country and its neighbourhood are becoming more belligerent, taking advantage of the pandemic and withdrawal of international forces. In this context, weeding out corruption in institutions, and strengthening anti-corruption mechanisms in the longer term, will be essential for Iraq’s government to begin restoring trust, and for armed forces to effectively respond to security threats and the resurgence of non-state belligerents.

Benedicte Aboul-Nasr is a Project Officer at Transparency International – Defence & Security. Her areas of focus are the MENA region, and how corruption affects conflict and security in the region.