A year on from the coup d’etat in Niger, Denitsa Zhelyazkova looks back at what has changed so far and what needs to happen to address corruption in the country’s defence sector.

Last month marked an important date for political leaders and human rights advocates all around the globe: one full year after the coup d’etat in Niger. On July 26, 2023, senior army officers from the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (Conseil National pour la Sauvegarde de la Patrie, or CNSP), led by General Abdourahamane Tchiani, seized power, suspended the constitution and detained country’s democratically elected leader, President Mohamed Bazoum. The junta claimed the reasons for the coup were the continuous deterioration of the security situation under Bazoum and poor economic management, among others. On August 20 that year, the coup leader proposed a three-year transition plan back to democratic rule, but concrete steps towards this have yet to materialise. Even though the 2023 mutiny was not a new phenomenon for the region, especially given the number of recent putsches in neighbouring Mali and Burkina Faso, this coup signifies a pivotal point in Nigerien politics.

Major changes since the coup

- Cutting ties with the West and regional actors: Niger is heading for a shift in strategic alliance and moving away from traditional Western security providers. Strengthening regional ties with Mali and Burkina Faso under a new mutual defence pact called the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) resulted in the new ‘Confederation of Sahel States’, emphasising both economic and military cooperation. They signed a treaty on the July 6 this year restating their sovereignty from France’s influence in the region, their departure from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), as well as their aim to create a new common currency. In addition to potentially having catastrophic economic and further humanitarian consequences, this step will likely complicate relations with neighbouring states and reshape international influence in the Sahel region.

- New anti-corruption body: General Tchiani has dissolved two of the country’s highest courts, the Court of Cassation and State Council, replacing them with a new anti-corruption Commission and a State Court. The commission’s main role will be recovering all illegally acquired and misappropriated public assets. Consisting of judges, army and police officers as well as representatives of civil society, the selection process of these members lacked transparency. Furthermore, it is not clear at this stage whether the anti-corruption regulations discussed under Bazoum will be implemented and whether the transitional commission and court can have an impact on that.

Damage

Turning away from democracy rarely leads to peace and stability.

In the immediate aftermath of the coup, violence and human rights abuses spiked, with Human Rights Watch reporting that CNSP supporters looted and set fire to the headquarters of Bazoum’s party, the Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS).

France, the EU, and the US condemned the coup and suspended development aid. UN humanitarian operations were also stopped. The African Union (AU) responded by suspending Niger, while ECOWAS closed its borders, demanded Bazoum’s release, and threatened military intervention and sanctions. Tensions escalated further as Mali and Burkina Faso warned that ECOWAS intervention would be considered a ‘declaration of war’ against them.

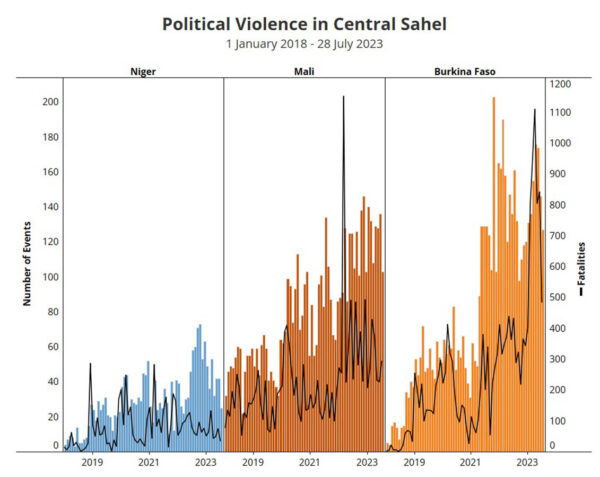

The putsch and its direct economic consequences are now threatening to worsen human suffering in the landlocked country that has been grappling with poverty, political instability and endemic corruption for decades. Being one of the poorest countries in world, Niger recently ranked 189 out of 193 territories in the critical HDI value from the UN’s Human Development Index, signalling a dire humanitarian crisis. Even though ECOWAS sanctions were lifted in February this year for humanitarian purposes, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported a surge in humanitarian need. An additional 600,000 people required humanitarian assistance in 2023, to an estimated total of some 4.3 million people, as extreme poverty is expected to reach 52%. Despite faring comparatively better against Burkina Faso and Mali in terms of fatalities, Niger is still suffering with violence and internal turmoil, with over 370,000 internally displaced people, primarily consisting of women and children.

ACLED graph using their own data on political violence, August 3, 2023.

The vicious cycle of conflict and corruption

Niger has been struggling with jihadist violence and security threats on several fronts, from IS Sahel and the al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM in the west and south of the country, to bandits, organised crime networks in resource-rich Agadez as well as Tahoua, and even Boko Haram rebels around Diffa near the border with Nigeria. Despite these serious security challenges, historically weak governance of the defence sector has been eroding Niger’s capabilities to defend its own citizens. An embezzlement case in 2020 revealed how a notorious arms dealer exploited government contracts for nearly a decade to funnel hundreds of millions of dollars to purchase weapons from Russia. With more than $130 million lost to corruption in this case alone, it brought to light just how urgent reform of the security sector, with anti-corruption at the core, is.

Now that the country is ruled by a military government, increased levels of secrecy are expected to rise around defence planning and spending, as well as personnel recruitment and payments. The newly adopted Ordinance 2024-05 of February 23, 2024, is a huge step backwards in terms of good governance in the security sector, allowing for even more opaque practices in defence budget planning and management. The new decree dictates that public procurement and public accounting expenses related to the acquisition of equipment, materials, supplies, as well as the performance of works or services intended for the Defense and Security Forces (FDS) are exempt from regular oversight regulations. Moreover, defence expenses are exempt from taxes, duties and fees during the transition period. Unfortunately, opaque practices have become the norm when it comes to Niger’s defence governance.

The 2020 iteration of Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) found that Niger faces a very high level of corruption risk, which is consistent with other fragile and conflict-affected states in the region. The results showcase the country’s issue with building robust institutions despite increased military spending and advanced operational training by Western allies in the past years. Scoring in the bottom quarter of the GDI 2020, Niger received the lowest score of all West African countries assessed in the index, with secrecy and opaque procurement practices being the biggest concerns. According to the 2013 Decree on defence and security procurement, Niger’s defence acquisition plan is not subject to public disclosure and is classified as “top secret,” nor is the plan subject to legislative scrutiny by the Security and Defence Committee. Despite the egregious 2020 embezzlement case, findings from a 2022 audit on state spending estimate budget discrepancies of approximately $99 million. Greater public oversight of defence spending, not expanded exemptions from transparency for the military and security services, is vital to restoring public trust and to ensure much-needed funds are not lost to corruption. Considering the new cooperation agreements with global actors notorious for the high levels of corruption risk in their defence sectors – such as Russia and Turkey – it is crucial for Niger to prioritise transparency and accountability in its defence governance.

One key rationale the military provided for the taking power last year was the worsening security in the country. However, violence has persisted and escalated, calling into question the effectiveness of military operations. Oversight of military spending has also been curtailed. Corruption in the defence sector not only hinders military capabilities, but also erodes public trust in the very institutions established to protect citizens. If opaque practices persist, allowing greedy officials to benefit while citizens continue to suffer, this can bring even more instability. Following the steps of Mail and Burkina Faso could potentially drag Niger into a vicious cycle of coups, violence, loss of territory to rebels, and of course the fuel driving the cycle – widespread corruption in the security sector. The path to democracy inevitably starts with focusing efforts on building resilient institutions and addressing corruption as a top priority through an urgent (and long-overdue) security sector reform.