Show Index: gdi

La corruption dans le secteur de la sécurité a un impact néfaste à la fois sur le secteur de la sécurité lui-même et sur la paix et la sécurité au sens plus large, en alimentant conflits et instabilité. Des études quantitatives ont mis en évidence la correlation entre corruption et instabilité étatique. Les états dominés par des systèmes fondés sur le clientélisme sont plus susceptibles de souffrir d’instabilité. Il est peu surprenant que 6 des 10 pays ayant obtenu le score le plus bas dans l’Indice de perception de la corruption 2019 se trouvent également parmi les 10 pays les moins pacifiques dans l’Indice mondial de la paix 2020. La corruption nuit à l’efficacité des forces de sécurité et porte atteinte à la perception qu’ont les populations de la légitimité des autorités centrales.

En retour, cela alimente un sentiment de désillusion, menaçant ainsi le contrat social et, en fin de compte, l’état de droit. Dans certaines situations, la corruption peut également faciliter l’expansion des groupes extrémistes et non-étatiques et est devenue l’un des piliers des discours de recrutement. En dénonçant la corruption de l’Etat, ces mêmes groupes se présentent comme une alternative légitime aux gouvernements et aux élites corrompus.

Associée à des éléments tels que la pauvreté, les violations des droits de l’homme, la marginalisation ethnique et la proliferation des armes de petit calibre, la corruption du secteur de la sécurité a eu un effet alarmant sur la sécurité humaine en Afrique de l’Ouest. Au cours des trois dernières décennies, la corruption a appuyé certains des pires épisodes de violence dont la region a été témoin. Des guerres civiles au Liberia et en Sierra Leone au conflit actuel au Nigeria, où la corruption endémique a affaibli les forces de défense et de sécurité, alimenté la rancoeur à l’encontre des représentants des États et permis aux acteurs armés non-étatiques de combler le vide, la corruption a été un dénominateur commun de la plupart des conflits dans la région.

Pendant des décennies, la stabilité en Afrique de l’Ouest a été grandement perturbée par les conflits internes, souvent financés par la vente illégale d’armes ou l’extraction illicite de ressources naturelles. Que ce soit au Liberia, en Sierra Leone et en Côte d’Ivoire ou au Mali, au Burkina Faso et au Nigeria, la corruption a souvent conforté ces conflits et est à l’origine de mécontentements à l’égard des dirigeants politiques ainsi que de changements politiques violents.

En ébranlant la confiance du public et en nuisant à l’efficacité des institutions de défense et de sécurité, la corruption a porté atteinte à l’état de droit et a engendré une instabilité prolongée. Concrètement, cela a résulté pour de nombreuses personnes en une dégradation de l’accès aux services de base et a contribué à la création d’environnements propices aux violations des droits de l’homme.

Ce rapport soutient que, étant donné la grande menace que la corruption représente pour la paix et la stabilité en Afrique de l’Ouest, une attention accrue doit être portée aux travaux visant à lutter contre la corruption dans le cadre de la G/RSS. Il analyse le lien entre la corruption et les conflits en Afrique de l’Ouest par rapport à la prévalence des efforts visant à lutter contre la corruption dans les cadres de travail normatifs de la RSS, couramment utilisés en Afrique de l’Ouest, ainsi que dans un échantillon de pays entreprenant une G/RSS.

Par le biais de ce cadre de travail, notre recherche révèle le délaissement des efforts de lutte contre la corruption au profit d’approches de « formation et d’équipement » plus techniques. En conséquence, les structures de gouvernance sous-jacentes restent non affectées et les réseaux de corruption intacts, ce qui représente une occasion manquée d’exploiter les capacités de la G/RSS afin d’entraîner un changement transformateur.

This policy brief explains how corruption in the security sector has a detrimental impact both on the security apparatus itself and on wider peace and security, by fuelling tensions and adding to conflict and instability.

Quantitative studies have underscored how corruption and state instability are correlated, with states dominated by narrow patronage-based systems more susceptible to instability. It is little surprise that six out of the 10 lowest-scoring countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 are also among the 10 least peaceful countries in the Global Peace Index 2020. Corruption undermines the efficiency of security forces, damages populations’ conception of the legitimacy of central authorities and feeds a sense of disillusionment, which threatens the social contract, and ultimately the rule of law. In some situations, corruption can also facilitate the expansion of non-state and extremist groups and has become one of the lynchpins of recruitment narratives, which position these groups as a legitimate alternative to corrupt governments and elites.

Intersecting with factors that includes poverty, human rights violations, ethnic marginalisation and proliferation of small arms, security sector corruption has had an alarmingly negative effect on human security in West Africa. For the past three decades, corruption has underpinned some of the worst episodes of violence the region has witnessed. From civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone to the ongoing conflict in Nigeria, where rampant corruption has weakened defence and security forces, fuelled resentment against states’ representatives and enabled non-state armed actors to fill the vacuum, corruption has been a common denominator of most conflicts in the region.

February 25, 2021 – Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts in West Africa are being undermined by a failure to address underlying corruption and a lack of accountability in the region’s security sectors, according to new research by Transparency International.

The Missing Element finds that strengthening accountability and governance of groups including the armed forces, law enforcement and intelligence services – not just providing training and new equipment – is a crucial but often neglected component to successful security sector reform (SSR).

By analysing examples from across West Africa, the report details how the high threat of corruption has undermined the rule of law, fuelled instability, and ultimately resulted in SSR efforts falling short of their objectives.

The report serves as a framework for policymakers to assess how corruption is fuelling conflict, then embed anti-corruption measures to reform the security sector into one which is more effective at maintaining peace and more accountable to the population it serves.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts across West Africa have focussed largely on providing training and equipment but rarely resulted in major change. This report details how a focus on anti-corruption and strengthening accountability has been the missing element. Only by recognising and understanding the impact of corruption in the defence and security sector and taking steps to combat it can these programmes hope to transform the sector into one which is both efficient and accountable.”

The Missing Element analyses security sector reform and governance in five countries that our research has previously flagged as being at a high risk of defence sector corruption: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria.

It concludes these interventions fell short because the focus was on providing practical support such as training programmes and new weapons and equipment (with between 80-90% of funding for SSR initiatives typically spent on these) rather than addressing underlying corruption.

The report assesses the main corruption risks in West Africa which are undermining SSR efforts, including:

Financial management

Limited or ineffective supervision over how defence budgets are spent present a huge corruption risk, but reforms to improve transparency in this area have often been neglected as part of SSR programmes.

National defence strategies in Niger and Nigeria are so shrouded in secrecy that it is impossible to determine whether defence purchases are legitimate attempts to meet strategic needs or individuals embezzling public funds. In Mali, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire, a lack of formal processes for controlling spending has resulted in numerous examples of unplanned and opportunistic purchases.

Defence sector oversight

Effective oversight and scrutiny of the defence sector by parliamentarians is essential to increase accountability and reduce opportunities for corruption, but despite being a key pillar of SSR, parliamentary oversight remains poor in West Africa.

In Ghana, only a handful of the 18 members of the Parliament Select Committee on Defence and Interior have the relevant technical expertise to perform their responsibilities. In Mali, the parliamentary body charged with scrutinising the defence sector was chaired by the president’s son until mid-2020. In Niger, the National Audit Office, which is responsible for auditing the defence sector’s spending, published its audit for 2014 in 2017.

Recommendations:

- SSR policymakers at institutional level, such as United Nations (UN), African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), to publicly acknowledge the nexus between corruption and conflict, and adapt SSR policy frameworks accordingly.

- SSR practitioners operating in West Africa to undertake corruption-responsive SSR assessments to better inform the design of national SSR strategies and in all phases of their implementation.

- SSR practitioners to build on anti-corruption expertise to ensure that corruption is addressed as an underlying cause of conflict.

Notes to editors:

Security sector refers to the institutions and personnel responsible for the management, provision and oversight of security in a country. Broadly, the security sector includes defence, law enforcement, corrections, intelligence services and institutions responsible for border management, customs and civil emergencies.

Security sector reform (SSR) is a process of assessment, review and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation led by national authorities that has as its goal the enhancement of effective and accountable security for the state and its peoples without discrimination and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law.

The five countries analysed in this report (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria) were previously assessed in Transparency International Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index.

About Transparency International Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.

For decades, stability in West Africa has been severely disrupted by internal conflicts, commonly financed by the illegal sale of arms or the illicit extraction of natural resources. From Liberia, Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire, to Mali, Burkina Faso and Nigeria, corruption has often underpinned these conflicts and is the basis for grievances against political leaders and violent political change.

By eroding public trust and undermining the efficiency of defence and security institutions, corruption has undermined the rule of law and contributed to sustained instability. In practice, this has resulted in weaker access to basic services for many and has contributed to the creation of environments conducive to human rights violations.

This report argues that, given the significant threat that corruption presents to peace and stability in West Africa, a greater focus should be placed on anti-corruption work within security sector reform and governance (SSR/G). It analyses the nexus between corruption and conflict in West Africa against the prevalence of anti-corruption efforts in normative SSR frameworks, commonly used in West Africa, and in a sample of countries undertaking SSR/G.

Through this framework, our research reveals the neglect of anti-corruption efforts, to the benefit of more technical “train-and-equip” approaches. As a result, this leaves underlying structures untouched and corrupt networks undisturbed, and represents a missed opportunity to harness the capacities of SSR/G to lead to transformative change.

New research from Transparency International Defence & Security warns of high corruption risk across CEE region

December 9 – Decades of progress towards greater democratisation across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) threatens to be undone unless urgent steps are taken to safeguard against corruption, new research from Transparency International warns.

The Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) finds more than half of the 15 countries assessed in the region face a high risk of corruption in their defence and security sectors.

Released today, Progress [Un]Made identifies region-wide issues which provide fertile ground for corruption and the deterioration of governance. These include weak parliamentary oversight of defence institutions, secretive procurement processes that hide spending from scrutiny, and concerted efforts to reduce transparency and access to information.

These issues are compounded by the huge amounts of money involved, with spiralling military expenditure in the CEE region topping US$104 billion in 2019 as many states continue to modernise their defence and security forces. The 15 states featured in the report are responsible for a quarter of this total with the majority increasing their defence budgets in the last decade.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

“Following major strides towards more robust defence governance in Central and Eastern Europe, many of these results should be a cause for concern. Corruption and weak governance in the defence and security sector is dangerous, divisive and wasteful. While it is encouraging to see a handful of countries score well the overall picture for the region is one of high corruption risk, especially around defence procurement – an area responsible for huge swathes of public spending.”

The GDI provides a detailed assessment of the corruption risks in national defence institutions by scoring each country out of 100 across five key risk areas: financial, operational, personnel, political, and procurement. Highlights from the CEE results include:

- Average score for the region is 48/100, indicating a high risk of corruption.

- Montenegro is judged to be at ‘very high’ risk with a score of 32, while Azerbaijan’s score of just 15 places it in the ‘critical’ risk category.

- High levels of transparency see Latvia fare the best in the region, with a score of 67 indicating a low risk of corruption.

- Authoritarian governments have weakened parliamentary oversight (Poland) and restricted access to information regimes (Hungary), closing off a key sector off from public debate and oversight.

We identify five key themes that are increasing corruption risk across the region, including:

Weak parliamentary oversight

Parliamentary oversight of defence is a key pillar in enforcing transparency and accountability but only two of the 15 countries we assessed have retained truly robust parliamentary oversight.

CEE regional average score: 51/100 (Moderate risk)

Best performers: 1) Latvia: 94/100 (Very low risk); 2) Lithuania: 83/100 (Very low risk)

Worst performers: 1) Azerbaijan 12/100 (Critical risk); 2) Hungary 27/100 (Very high risk)

Opaque procurement processes

Allowing companies to bid for defence contracts helps reduce the opportunities for corruption and ensure best value for taxpayers, but our analysis highlights that open competition in this area is still the exception rather than the norm.

CEE regional average score: 47/100 (High risk)

Best performers: 1) North Macedonia 82/100 (Low risk); 2) Estonia: 74/100 (Low risk)

Worst performers: 1) Azerbaijan 8/100 (Critical risk); 2) Hungary 14/100 (Critical risk)

Attacks on access to information regimes

Access to information is one of the basic principles of good governance, but national security exemptions and over-classification shield large parts of the defence sector from public view.

CEE regional average score: 55/100 (Moderate risk)

Best performers: 1) Georgia, Latvia, North Macedonia, Poland 88/100 (Very low risk); 2) Lithuania: 75/100 (low risk)

Worst performers: 1) Azerbaijan 13/100 (Critical risk); 2) Hungary 25/100 (Very high risk)

To make real progress and strengthen the governance of the defence sector in the region, Transparency International calls on governments across the region to:

- Respect the independence of parliaments and audit institutions and provide them with the information and time they need to perform their crucial oversight role.

- Overhaul their procurement systems to ensure more competition and transparency.

- Guarantee transparent and effective access to information and implement a clear rationale on the use of the national security exception, as well as transparency over how the rationale is applied.

Notes to editors:

Progress [Un]Made – Defence Governance in Central and Eastern Europe can be downloaded here.

The CEE region spent US$104 billion on defence and security in 2019. This total includes Russia, which spent US$65 billion. Lithuania and Latvia increased military spending by 232 per cent and 176 per cent respectively between 2010 and 2019, and Poland by 51 per cent over the same period. Armenia and Azerbaijan consistently spend close to 4% of GDP on defence and are among the most militarised countries in the world.

Whilst defence governance standards in Europe are some of the most robust globally, states in Central and Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, where a combination rising defence budgets and challenges to democratic institutions, are particularly vulnerable to setbacks to their recent progress in governance and development.

In Armenia, Albania, Hungary, Kosovo, Montenegro, Poland and Serbia, there is a notable tendency for parliaments to align themselves with the executive on defence matters, for example by passing executive-sponsored legislation with no or only minor amendments.

In Georgia, secret procurement accounted for 51 per cent of total procurement procedures from 2015-2017. In Ukraine that figure is 45 per cent, while in Poland it is as high as 70 per cent. In Lithuania, open competition accounted for as little as 0.5 per cent of procurement procedures, with upwards of 93 per cent of defence procurement conducted through restricted tenders and negotiated procedures.

In Hungary, the government has made it harder to access information by skewing the rules in favour of public bodies and imposing new fees on those who lodge requests. In Estonia, the 2013 access to information act contained 7 exceptions, with 1 related to defence; by 2018, there were 26 exceptions, with 7 related to defence. Just three of the 15 states we assessed – Lithuania, Latvia and Georgia – were found to have been responding to freedom of requests promptly and mostly in full.

About Transparency International

Through chapters in more than 100 countries, Transparency International has been leading the fight against corruption for the last 27 years.

About the Government Defence Integrity Index

The GDI is the only global assessment of the governance of and corruption risks in defence sectors, based upon 212 indicators in five risk categories: political, financial, personnel, operations and procurement.

The Central and Eastern Europe wave includes assessments for 15 countries: Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kosovo, Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia. All states are either EU/NATO members or accession/partner states.

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI). The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. This means overall country scores from this 2020 version cannot be accurately compared with country scores from previous iterations of the Index.

Subsequent GDI results will be released in 2021, covering Latin America, G-20 countries, the Asia Pacific region, East and Southern Africa, and NATO+.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340 (out of hours)

This report examines the quality and effectiveness of defence governance across fifteen countries in Central and Eastern Europe: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia and Ukraine. It analyses vulnerabilities to corruption risk and the strength of institutional safeguards against corruption across national defence sectors, drawing on data collected as part of Transparency International Defence & Security’s (TI-DS) Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI).

It is intended to provide governments and policymakers with an analysis of defence governance standards in the region and supply civil society with an evidence base that will facilitate their engagement with defence establishments and support advocacy for reforms that will enhance the transparency, effectiveness and accountability of these institutions.

This report details good practice guidelines and policy implications that are designed to reduce the opportunities for corruption and improve the quality of defence governance in Central and Eastern Europe. It identifies five key issues of defence governance where improvements are urgently needed in order to mitigate corruption risks: parliamentary oversight, defence procurement, transparency and access to information, whistleblowing, and military operations.

By Benedicte Aboul-Nasr, Project Officer, Transparency International – Defence & Security

On October 17, 2019, Lebanese citizens took to the streets in response to a government proposal to tax WhatsApp communications, in what would become known as the “Thawra”, or “Uprising” against widespread corruption and worsening economic conditions. A year after the beginning of the protests, and two months after the explosion in the Port of Beirut killed 191 people, injured over 6,500, and uprooted nearly 300,000, Lebanese citizens still have no clear answers as to why for six years, 2,700 tons of explosive chemicals were stored in hazardous conditions at the heart of Lebanon’s capital. Many suspect that a long history of negligence and corruption, the very factors that pushed people to the streets last year, are at least partly responsible for the devastation that took place on August 4, 2020.

The government response has been uneven and in the aftermath of the explosion authorities were slow to support immediate relief efforts. Instead, when Lebanese protesters took to the streets on August 8 to voice their anger towards a political class that many believe has benefited from Lebanese resources for decades, security forces responded harshly, deploying tear gas and live ammunition against protesters. Two days later, Hassan Diab’s government resigned, noting that corruption in Lebanon is “bigger than the state”. And, on August 13, eight days after the explosion, Parliament voted for a state of emergency, giving defence forces a broader mandate than the one they already had under the general mobilisation adopted to help contain COVID-19. Since then, Prime Minister-designate Mustapha Adib stepped down, within a month of his nomination, having failed to achieve the consensus necessary to form a government. At the time of writing, Lebanon remains in a political impasse, while former Prime Minister Hariri, who had stepped down two weeks into the protests in October 2019, is in the running to replace his successor.

Allegations of government corruption are not isolated incidents, and mismanagement has led to numerous crises and leadership vacuums over the years, which paved the way for the protest movement. Lebanon is now facing one of the most serious financial crises in its history which has crippled the economy. The state has defaulted on debt payments and banks are imposing de facto capital controls on withdrawals while Carnegie’s Middle East Center estimates that close to US$800 million were transferred out of the country within the first three weeks of the protests. The Lira lost 80% of its value over nine months; by July this year and Lebanon became the first country in the region to enter hyperinflation. Even before the COVID-19 crisis hit, the World Bank had estimated that up to 45% of Lebanese citizens would be below the poverty line by the end of 2020. Despite undeniable evidence that the situation was untenable, prior to the explosion, discussions with the IMF had been stalled for months, and Alain Bifani, the finance ministry’s director-general, had resigned over state officials’ unwillingness to acknowledge the scale of the crisis and achieve consensus to identify solutions. The contract for a forensic audit of the Central Bank was only signed in August, and the audit itself did not begin until September.

The international community has offered loans and significant humanitarian aid to support victims and the reconstruction of Beirut. Tellingly, several governments have pledged that they would not disburse aid through the government, and are prioritising non-governmental organisations that have been at the forefront of assessment and reconstruction needs. Aid disbursed through the government, and renewed commitments to unlock funds promised by the CEDRE conference in 2018, are conditional on stringent anti-corruption reforms being adopted and must be accompanied by strict oversight. In this regard, it is crucial that Lebanese civil society and non-profit organisations are granted access to sufficient information to oversee the disbursement of aid and prevent funds from being lost.

As part of the broader powers and responsibilities granted to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) under the state of emergency proclaimed after the explosion, the military has been given the crucial role of coordinating the distribution of humanitarian aid and supporting other public bodies in their reconstruction efforts. In carrying out these roles, and with the additional powers from which they benefit, it is crucial that the LAF ensure the highest standards of integrity and transparency with the Lebanese public. The LAF has benefitted from a high level of trust in the past, and remains one of the most representative branches of government – the institution must ensure that it maintains trust and supports ways forward for the Lebanese, in particular as Lebanese citizens and organisations rebuild.

The coming months will be crucial for Beirut’s reconstruction and to help lift Lebanon out of the crisis it is experiencing. Anti-corruption measures and transparency, not only in the disbursement of aid but also in reform efforts, should be prioritised by the armed forces themselves, and more broadly by an incoming government committed to resolve the financial and political crises Lebanon currently faces as the country seeks international support. The Lebanese Transparency Association (LTA), Transparency International’s national chapter in Lebanon, has been advocating alongside Transparency International – Defence & Security for increased transparency and accountability of the defence sector since 2018. In 2020, LTA continued to emphasise the urgent need for further transparency with constituents, and for the armed forces to implement access to information legislation to allow Lebanese citizens to understand how the body functions. As the LAF maintain responsibility in the aftermath of the explosion, both for aid disbursement and for maintaining security alongside security forces, clear communications and oversight of the defence sector are critical.

The explosion and its aftermath have brought issues that Lebanese citizens were familiar with – and which pushed many to the streets over the last year – to the forefront of Lebanon’s dealings with the international community. Only by tackling the root causes, continuing to push for reform, and beginning to rebuild institutions in which the public can trust, will Lebanon have a chance to become more stable and pave a way out of the crisis. Lebanese politicians have often shown willingness to commit to reforms when dealing with the international community in the past. However; reforms have then stalled due to a lack of consensus, for instance leading to delays in implementing access to information legislation, or in selecting members for the National Anti-Corruption Commission. As the international community aims to support Lebanese citizens and help rebuild Beirut, they should be wary of attempts to divert assistance, and of mismanagement in the disbursement of funds. Instead, any international and national initiatives should support Lebanese citizens’ calls to dismantle the root causes of corruption, for the political class to seriously address the financial crisis, and for concrete and measurable steps for reform and accountability.

Benedicte Aboul-Nasr is Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Project Officer working on Conflict and Insecurity, with a focus on the MENA region. She has a background in international humanitarian law and the protection of civilians, and currently researches links between corruption and situations of crisis and conflict.

Governance reforms, including to security sector, are urgently needed

23 October 2020 – Transparency International condemns the Nigerian state’s excessive use of force and the continued perpetration of violence against peaceful protesters.

Protests that began with demands for an end to police brutality and the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), have since transformed into wider calls for an end to corruption and the looting of public funds. The government must respond to these calls with serious evidence-based anti-corruption reforms, including to the security sector, in dialogue with civil society.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said: “The appalling violence we have seen against peaceful protestors has to end. The only way to restore the much-needed trust in relations between Nigerian citizens and the security sector is to respect and protect basic human rights. Further repressive actions against legitimate demands for an improved security sector in Nigeria will only escalate the situation.”

Nigeria’s score on the Government Defence Integrity Index by Transparency International – Defence & Security rates corruption risks in the country’s security sector as Very High, with extremely limited controls in operations and procurement. While oversight mechanisms are in place, they often lack coordination, expertise, resources, and adequate information to fully perform their role.

In addition, Nigeria has seen no significant improvement in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index since the current methodology was introduced in 2012. The 2019 Global Corruption Barometer for Africa found that Nigerians rate the police as the most corrupt institution in the country. Almost half of those surveyed reported paying a bribe to the police in the previous 12 months.

Delia Ferreira Rubio, Chair of Transparency International, said: “Corruption deprives ordinary people of their rights to peace, health, security and prosperity. It robs young people of a future in which they can fulfil their potential, and it misappropriates the wealth of a nation for the benefit of the few. Peaceful protesters exercising their right to freedom of assembly must never be met with violence and brutality. Citizens’ demands for an end to corruption must be heard and acted upon.”

Auwal Musa Rafsanjani, Executive Director of the Civil Society Legal Advocacy Centre (CISLAC), Transparency International’s national chapter in Nigeria, said: “The government of Nigeria must immediately stop deploying troops against protestors. The young people who have taken to the streets have a constitutional right to express their grievances through peaceful protest without facing violence and brutality from the state. Together with our civil society partners in Nigeria, we stand ready to work with the government on the root and branch reforms needed to the police and security agencies, and to stop the looting of public funds through corruption. We also condemn the violence and the destruction of property by groups that have infiltrated the peaceful protests.”

New report warns weak regulations leave door open to undue influence

October 21 – German defence policy risks being influenced by corporate interests, new research by Transparency International – Defence & Security warns.

Released today, Defence Industry Influence in Germany: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the German Policy Agenda details how defence companies can use their access to policymakers – secured through practices such as secretive lobbying and engagements of former public officials – to exert considerable influence over security and defence decision making.

The report finds that gaps in regulations and under-enforcement of existing rules combined with an over-reliance by the German government on defence industry expertise allows this influence to remain out of the reach of effective public scrutiny. This provides industry actors with the opportunity to align public defence policy with their own private interests.

To address these shortcomings, new controls, oversight mechanisms need to be put in place and sanctions should be applied to regulate third party influence in favour of the common good and national security.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

“Decisions and policy making related to defence and security are at particularly high risk of undue influence by corporate and private interests due to the high financial stakes, topic complexity and close relations between public officials and defence companies. Failing to strengthen safeguards and sanction those who flout the rules raises the risk that defence decision making and public funds are hijacked in favour of private interests.”

The report shows how lax rules around policymakers declaring conflicts of interest, and lack of adequate penalties for failing to disclose them, leaves the door open to MPs wishing to take up lucrative side-jobs. Frequent and prominent cases of job switches between the public and private defence sector compound issues of conflicts of interest and close personal relationships with inadequate oversight.

And, due to a lack of internal capacity, Germany’s defence institutions are increasingly outsourcing key competencies to industry, allowing defence companies crucial access to defence policy. The procurement of these external advisory services is not subject to appropriate oversight.

While the German constitution requires a strict control over excessive corporate influence in public sectors, too often this is not sufficiently exercised due to a lack of technical and human resources within government and parliament. In addition, insufficiently enforced legal regulations and a lack of transparency of lobbying activities enables undue influence to occur in the shadows outside of public scrutiny.

Greater transparency is necessary to ensure accountability

National security exemptions are common in the defence sector and enable institutions to override transparency obligations in favour of secrecy. However, protecting national security and ensuring the public’s right to information can both be achieved by striking the right balance where information is only classified based on a clear justification for secrecy. Transparency in defence is crucial to ensuring effective scrutiny in identifying and controlling undue influence.

“Despite the justification for secrecy in this policy area the greatest possible transparency must be created to ensure control by parliament and the public. If, in addition, human resources and expertise are lacking, advice from corporate lobbyists receive easy access,” said Peter Conze, security and defence expert at Transparency International Germany.

New lobbying register does not go far enough: we need a legislative footprint

The lack of transparency around lobbying in Germany allows industry actors to exert exceptional influence over public policy.

While Germany’s proposed new lobbying register provides a positive step towards transparency, it does not go far enough to allow effective scrutiny. External influence on legislative processes and important procurement decisions remains unaccountable without the publication of a legislative or decision-making footprint, which details the time, person and subject of a legislator’s contact with a stakeholder and documents external inputs into draft legislation or key procurement decisions.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is calling on the German government to:

- Expand the remit of the proposed lobbying register to cover the federal ministries and industry actors.

- Include requirements for a ‘legislative footprint’ that covers procurement decisions in addition to laws. The legislative footprint should outline the inputs and advice that have contributed to the drafting of laws or key policies, and substantially increase transparency in public sector lobbying.

- Introduce an effective and well-resourced permanent outsourcing review board within the Ministry of Defence to verify the necessity of external services and their appropriate oversight.

- Strengthen the defence expertise and capacity within the independent scientific service of the Bundestag, or to create a dedicated parliamentary body responsible for providing MPs with expertise and analysis on defence issues.

Notes to editors:

- The report “Analysis of the influence of the arms industry on politics in Germany” was prepared by Transparency International – Defence & Security with the support of Transparency International Germany.

- The report examined structures, processes and legal regulations designed to ensure transparency and control based on 30 expert interviews. The report is part of a comprehensive study of the influence of the defence industry on politics in several European countries.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

This report examines systemic vulnerabilities and influence pathways through which the German defence industry may exert inappropriate influence on the national defence and security agenda. Governments and industry should mitigate the risk of undue influence by strengthening the integrity of institutions and policy processes and improving the control and transparency of influence in the defence sector. Compiled by Transparency International Defence and Security with the support of Transparency International Germany, this report forms a case study as part of a broader project to analyse the influence of the arms industry on the defence and security agendas of European countries. Alongside Italy, Germany was selected as a case study due to its defence industry characteristics, industry-state relations, lobbying regulations and defence governance characteristics. The information, analysis and recommendations presented in this report are based on extensive research that has been honed during more than 30 interviews with a broad range of stakeholders and experts.

With security threatened by increasingly belligerent armed actors and a hastened drawdown of international troops due to COVID-19, Iraq cannot afford to leave its defence institutions open to corruption.

By Benedicte Aboul-Nasr

Since October 2019, Iraq has seen tensions in its political sphere, including public protests, declining oil prices, increasing risks of proxy war between the US and Iran, and the resurgence of violent armed groups; the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated an already precarious security situation. After six months without a government, Iraq’s parliament appointed Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi in May 2020, and granted his full cabinet confidence in June. To respond to the state’s most urgent priorities, the incoming government and its international partners should urgently consider addressing risks of corruption and human rights violations, in particular in the defence sector, to guarantee that the defence forces have the capacity, resources, and popular backing, to respond to priorities.

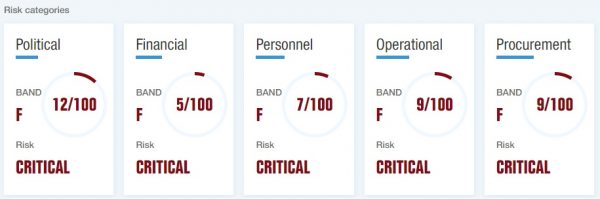

In research published this week, Transparency International – Defence & Security has found Iraq’s defence sector to be at critical risk of corruption, and lacking anti-corruption and transparency mechanisms. In fact, our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) indicates that Iraq is particularly vulnerable to risks relating to finances and personnel, and does not fare much better in the areas of political, operational, and procurement corruption risks, with an overall score of 9/100 on the Index. Corruption has been linked to the erosion of institutions and of trust, and is one of the main grievances driving the protests that broke out last October. As critical as these results are, they offer the new government a blank slate to meaningfully reform the defence sector from the ground up; this will be imperative to secure longer-term security for the country.

COVID-19 has added another threat; the crisis has severely affected Iraqi citizens, as security forces enforce curfews against a backdrop of unrest and accusations of forces deliberately firing on protesters, killing over 600, injuring thousands, and recent reports of ill-treatment and torture of anti-government protesters. It is also likely to disproportionately affect displaced populations, more vulnerable to the pandemic following years of conflict and displacement, with more poorly resourced accommodation, protection, and health systems. Crucially, the pandemic has also generated additional security challenges, as the government and defence institutions redirect resources towards its pandemic response, while simultaneously countering the apparent resurgence of extremist groups. Indeed, Iraq is already facing the resurgence of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which are seeking to exploit the governance vacuum and the pandemic to resurface.

Governments around the globe have rapidly shifted their own priorities in response to COVID-19. Within weeks of the outbreak, France, Canada, the United States and several European countries in the global coalition against ISIL announced temporary withdrawals of their troops from Iraq and from NATO Mission – Iraq. Meanwhile, Operation Inherent Resolve announced that it had stopped training Iraqi security forces, as the Iraqi military also suspended its trainings to reduce the spread of the virus. Against this backdrop, ISIL has actively called for its members to ‘act’, encouraging supporters to ‘exploit disorder’ and is increasing the pace and violence of attacks, taking advantage of the drawdown of international troops.

Countering corruption risks in defence must therefore become a priority. Doing so would limit the risks of abuses of civilian populations, illegal trade of cultural property, of theft or diversion of already limited resources, and would ensure that Iraq’s defence institutions can respond to the multiple challenges it faces. Iraq has seen the consequences of a poorly governed and corrupt defence sector: the military cannot afford vulnerabilities akin to those that enabled the rise of ISIL in 2014. At the time, corruption fuelled problems which left troops hollowed out and outnumbered, such as equipment theft and ‘ghost soldiers’ – members of the military whose names were registered and salaries disbursed, without being present in military ranks. ISIL actively used these issues as recruitment tools in its propaganda, and militants developed government functions in areas where relations with government had deteriorated for years. The group benefitted more concretely from the erosion of security services, where corruption had thrived, to take over swathes of territory, leading to the prolongation of the conflict. Despite the military defeat of the group in 2018, these vulnerabilities remain and risk weakening the Iraqi armed forces when they are most needed.

Iraq’s defence institutions and oversight are severely lacking, and do not fulfil basic requirements of anti-corruption and transparency. Yet they can no longer afford a weak stance on corruption, nor on human rights. To avoid exploitation of existing vulnerabilities and erosion of the defence and security forces similar to those that led to Mosul’s fall in 2014, the government must turn its attention to defence governance, and tackle existing vulnerabilities such as those highlighted by the GDI. The incoming government is in a unique position to do so, and has already pledged to investigate the allegations of torture disclosed by the UN. The government could also take concrete steps and measures to strengthen integrity and accountability within the armed forces. In addition, both the new Defence Minister, Juma Inad, and Interior Minister, Osman Ghanimi, have extensive and highly respected military backgrounds and an in depth understanding of Iraq’s security challenges which could support reform of the defence and security sectors.

International partners have a critical role to play and should actively promote instilling anti-corruption systems into longer-term institution building and reconstruction efforts. For instance, international partners should prioritise including anti-corruption and integrity building within training courses and partnerships with the armed forces. They could also, as a means of supporting longer term development of defence institutions, support the development of accountability structures, such as streamlining a code of conduct for all military forces, developing and implementing mechanisms to allow whistle-blowing and whistle-blower protections within the armed forces, and setting up clear systems for investigations of allegations of abuse.

Armed groups in the country and its neighbourhood are becoming more belligerent, taking advantage of the pandemic and withdrawal of international forces. In this context, weeding out corruption in institutions, and strengthening anti-corruption mechanisms in the longer term, will be essential for Iraq’s government to begin restoring trust, and for armed forces to effectively respond to security threats and the resurgence of non-state belligerents.

Benedicte Aboul-Nasr is a Project Officer at Transparency International – Defence & Security. Her areas of focus are the MENA region, and how corruption affects conflict and security in the region.