By Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy at Transparency International Defence & Security

Last week the US President issued a government memorandum making corruption a core national security concern.

Transparency International’s new research reveals there is good cause for concern. The 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) shows that nearly two-thirds of countries – 62 per cent – face a high to critical risk of corruption in their defence and security sectors.

Countries that score poorly in the GDI have weak or non-existent safeguards against defence sector corruption. They are more likely to experience conflict, instability, and human rights abuses. Sudan, which has just undergone a military coup, came bottom of the Index with a score of 5/100 while New Zealand came top with a score of 85/100.

The GDI findings should ring alarm bells in governments around the world; particularly as global military spending has increased to some $2 trillion annually, fuelling the scale and opportunity for abuse.

Corruption in a nation’s defence institutions weakens security forces and threatens wider peace and stability. It eats away at public trust in the state and the rule of law, giving vital oxygen to non-state and extremist armed groups. It leaves governments unable to properly protect their citizens – their primary function. We have seen examples time and time again. Think of Iraq, when in 2014 50,000 ‘ghost soldiers’ (troops that exist only on paper) were found on the books. Their salaries were either stolen by senior officers or split between soldiers and high-ranking officers. The phenomenon has a human and financial cost leaving forces depleted, unprepared to face real threats and unable to fulfil their mandate to protect citizens and provide national security.

The GDI provides defence institutions across 86 nations with a comprehensive assessment of their corruption risk and a platform to identify the safeguards needed to prevent corruption. It does not measure corruption itself. It is not concerned with calculating stolen government funds, identifying corrupt figures, nor even estimating how corrupt the public thinks their defence forces are.

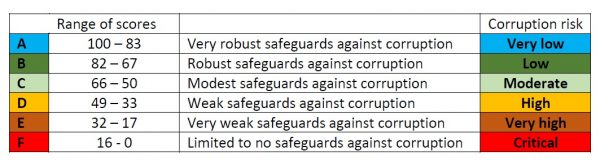

Rather, the GDI offers a roadmap for better governance of the defence sector. It maps out gaps in policies and practices that can prevent corruption and provides standards that countries can follow to strengthen their systems, across five main risk areas: policymaking and political affairs, finances, personnel management, military operations, and procurement. It assigns a score out of 100 and ranks countries from A (very robust safeguards) to F (limited to no safeguards against corruption).

Military operations

The GDI results are particularly poor when it comes to military deployments for internal security operations and peacekeeping missions overseas. Almost every country assessed performs badly in terms of anti-corruption safeguards in this area. That includes nations most actively engaged in international missions. Bangladesh scores 0/100 operationally yet is the top contributor of uniformed troops to UN peacekeeping missions.

Countries facing internal threats fare no better when it comes to military operations. A lack of anti-corruption safeguards means troops may be more likely to contribute to exacerbating conflict rather than bringing about peace.

These findings leave little doubt that governments are overlooking the corrosive impact of defence and security corruption despite its clear threat to peace, stability and human life.

Arms trade

The GDI also reveals significant corruption risks among the world’s major arms suppliers and recipients.

Eighty-six percent of global arms exports between 2016-2020 were from countries with a moderate to very high risk of corruption. For major arms suppliers, the GDI exposes poor parliamentary scrutiny, transparency and oversight in export and procurement processes. The top five exporters accounted for 76% of the global total.

Meanwhile, just under half – 49% – of global arms imports are to countries with a high to critical risk of defence corruption. These countries lack the policies and systems to independently oversee these deals or how these weapons will be used. Nor do they provide meaningful data on how they choose which companies to buy from or whether any third parties are involved. This lack of transparency leaves the door wide open to bribery, theft of public money and to weapons finding their way into the hands of criminal gangs or insurgent groups.

Overall, the GDI paints a dismal picture of a defence sector that continues to operate in secrecy, with inadequate policies and procedures to mitigate high corruption risks. This lack of transparency and accountability sets the scene for government activity that has devastating consequences for civilians and global security.

If governments are serious about building national and international security and stability, they must embed transparency and anti-corruption at the core of defence institutions. Getting this right is vital to averting future conflict, failed interventions and the devastating human cost that comes with them. To see the GDI results in detail go to https://ti-defence.org/gdi