Theme: Operations

Corruption undermines the legitimacy and effectiveness of government institutions in all sectors, but it thrives in areas where large budgets intersect with high levels of secrecy and limited accountability, write Michael Ofori-Mensah, Denitsa Zhelyazkova and Harvey Gavin.

The defence and security sector features all these risk areas, making it particularly vulnerable. The combination of secrecy, limited oversight and, often, high levels of discretionary power in decision-making, creates an environment ripe for corruption. This vulnerability not only undermines the ability of governments to fulfil their primary duty to their citizens of keeping them safe, it also undermines their legitimacy.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is working to address this issue. A key contribution is our recent involvement in NATO’s Building Integrity Institutional Enhancement Course. This program focuses on supporting national governments with capacity building in developing Integrity Action Plans aimed at strengthening the integrity of their defence institutions. Before drawing up these plans, defence officials must identify areas most at risk of corruption. This is where the recent enhancement aimed at improving accessibility and use of our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) becomes an invaluable diagnostic tool.

The GDI is the world’s leading assessment of corruption risks in national defence institutions. As a corruption risk assessment tool, it examines the quality of institutional controls to manage the risk of corruption in nearly 90 countries around the world on both policymaking and public sector governance and covers five major risk areas:

- Financial: includes strength of safeguards around military asset disposals, whether a country allows military-owned businesses, and whether the full extent of military spending is publicly disclosed.

- Operational: includes corruption risk in a country’s military deployments overseas and the use of private security companies.

- Personnel: includes how resilient defence sector payroll, promotions and appointments are to corruption, and the strength of safeguards against corruption to avoid conscription or recruitment.

- Political: includes transparency over defence & security policy, openness in defence budgets, and strength of anti-corruption checks surrounding arms exports.

- Procurement: includes corruption risk around tenders and how contracts are awarded, the use of agents/brokers as middlemen in procurement, and assessment of how vulnerable a country is to corruption in offset contracts.

Within these areas, the GDI identifies 29 specific corruption risks, assessed through 77 main questions and 212 underlying indicators. These indicators examine both legal frameworks and their implementation, as well as the allocation of resources and outcomes.

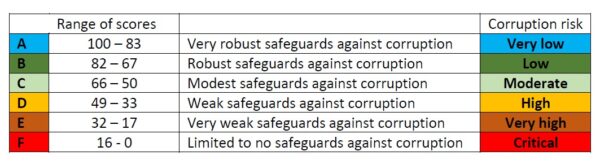

It, therefore, provides defence institutions with a comprehensive assessment of corruption vulnerabilities and a platform to identify safeguards against corruption risks. Each indicator is scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with aggregated scores determining the strength of a country’s institutional practices and protocols to manage corruption risks in defence,: from A (low corruption risk/very robust institutional resilience to corruption) to F (high corruption risk/limited to no institutional resilience to corruption).

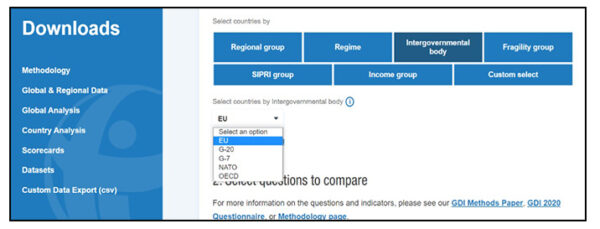

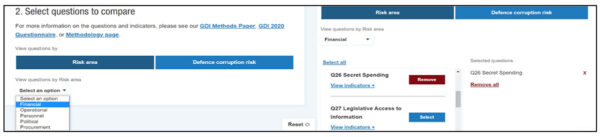

Our recent updates to the GDI website have significantly improved its functionality, allowing users to group countries by various categories such as region, income level, regime type, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) group and intergovernmental body affiliation. For example, policymakers seeking to understand problematic areas within the EU defence sector can now explore specific indicators of interest and export the data for detailed analysis.

The enhancement also provides a functionality that enables comparisons across the 77 main questions of the GDI thus facilitating targeted assessments of particular risk areas and cross-country analysis.

Data from the GDI, both quantitative and qualitative, can be downloaded in .csv format, compatible with numerous data processing tools like Excel, SPSS, and Access. This feature allows users to generate customised spreadsheets containing only the information pertinent to their needs. The qualitative data, derived from expert assessor interviews, provides critical insights that complement the quantitative scores, offering a nuanced understanding of corruption risks.

(Note: these updates apply to the current 2020 iteration of the GDI. Our team is working on the 2025 GDI – you can find more information about it here)

The ongoing challenges posed by corruption in the defence sector demand sustained and coordinated efforts from both national governments and the international community. Initiatives like NATO’s Building Integrity Institutional Enhancement Course, supported by tools like the GDI, represent significant strides toward fostering good governance in defence institutions. But maintaining high standards of defence governance remains an ongoing challenge that requires vigilance and commitment.

Reforms are urgently needed to address the institutional gaps identified by the GDI. Integrity Action Plans, informed by comprehensive corruption risk assessments, are essential for guiding these changes. By prioritising transparency, accountability and resilience, countries can strengthen their defence institutions, reduce corruption and improve peace and security.

The Geneva Peace Week (GPW) is one of the important appointments on the international peacebuilding calendar, writes Francesca Grandi, our Senior Advocacy Expert. This year, it centred around the question: “What is Peace?”

A call to action and an opportunity for reflection, the forum brought together a wide array of stakeholders from the peace and security ecosystem and beyond, highlighting the cross-cutting nature of peacebuilding and the need for innovative and collaborative solutions for building lasting peace.

Building bridges

Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) attended GPW 2024 to make the case for recognising corruption in the defence and security sectors as a key driver of violence and armed conflict, and to advocate for a more comprehensive and systematic inclusion anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding frameworks. We introduced our research and engaged with many panels. Colleagues in international NGOs, UN bodies, and Member States expressed a genuine interest in our work and acknowledged the importance of addressing corruption in the defence and security sector to build trust and resilience in fragile contexts. It was clear that more research and practical tools are needed to bridge what we know about corruption and armed conflict.

Anti-corruption as a preventive tool

In nearly every session, the themes of prevention, trust-building, and institutional resilience resonated strongly with our message that anti-corruption contributes to postive peace and security outcomes and provides a relevant lens across a wide range of peace and security issues.

Corruption hampers the effectiveness of security sector reforms, arms controls, and truth and reconciliation processes; it undermines the protection and promotion of human rights; it erodes trust between former combatants and government institutions, and thus the successful reintegration of ex-combatants, increasing the likelihood of conflict relapse.

We asked whether corruption is sufficiently integrated into international peace frameworks, such as the UN Pact for the Future. While some peacekeeping mandates include anti-corruption provisions, the absence of explicit references in key documents remains a concerning omission.

By addressing corruption as a root cause of conflict and ensuring that public resources are used as intended, we can build more resilient and inclusive societies and enhance the impact of localised and gender-responsive peacebuilding approaches. By integrating anti-corruption strategies in our peace responses, we can strengthen institutional integrity and help foster the public trust and the institutional resilience needed for lasting peace.

Next steps: Expanding partnerships and advocating

Moving forward, TI-DS remains committed to advocating for integrating anti-corruption as a key component of the global peace and security agenda and for including corruption prevention strategies in future peace interventions, emphasising their role in strengthening governance and peace processes.

As we continue our advocacy efforts, our focus remains on building partnerships, producing evidence-based research, and ensuring that anti-corruption remains at the forefront of global peace and security discussions. The GPW provided us with a platform to advance these objectives, and we look forward to furthering our work in this vital space.

As members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) gather this week in Laos for the 44th and 45th ASEAN Summits, this blog by Yi Kang Choo, our International Programmes Officer, explores the concerning absence of a strong focus on corruption risks – particularly in the region’s defence and security sectors.

Given the steady rise in military spending in the region, the ongoing civil war in Myanmar, and heightened tensions over territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea involving ASEAN nations, a discussion about how to root out corruption, and increase resilience to it, in these sectors seems overdue.

Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), alongside national TI Chapters in Indonesia (TI-ID) and Malaysia (TI-M) urge ASEAN states to recognise the pressing threat that corruption in the defence sector poses to regional peace and security. As Malaysia prepares to take on the role of ASEAN Chair in 2025, Transparency International Malaysia specifically highlights the crucial need for Malaysia especially to champion collective anti-corruption initiatives, particularly within defence and security sectors across the region. Malaysia needs to use its leadership by demonstrating that it is executing its national anti-corruption strategies with greater transparency and how such initiatives will help the ASEAN region as a whole.

Recent data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) highlights that global military expenditure reached a record high of $2.443 trillion in 2023, with ASEAN member states seeing an average rise of 2.34% since 2022. As our research shows, increased defence spending without appropriate oversight often correlates with rising corruption risks. In systems already susceptible to corruption, an influx of funds is most likely to benefit corrupt actors, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that prioritises private gains over peace and security outcomes.

Our Government Defence Integrity (GDI) Index shows nearly half of all ASEAN member states face high to critical corruption risks in their defence sectors. This includes Malaysia, the incoming ASEAN Chair in 2025. Corruption can severely undermine the reliability and quality of military infrastructure and equipment, divert critical public resources, and compromise the safety and operational effectiveness of armed forces during potentially critical situations.

Additionally, effective civilian oversight of defence institutions remains limited across the region, especially given the restrictive civic spaces in all ten ASEAN countries, which have been categorised as ‘closed’, ‘repressed’, or ‘obstructed’ according to 2023 CIVICUS Monitor rating.

To address these urgent challenges, TI-DS calls on ASEAN member states to:

- Recognise and respond to corruption as a threat to peace and security – Corruption exacerbates inequalities within and between nations, fuelling conflicts and geopolitical tensions. ASEAN must prioritise strengthening governance systems, embedding corruption safeguards, and building integrity within its armed forces into defence and security decision-making.

- Create mechanisms for meaningful civil society engagement and effective parliamentary and civilian oversight in defence and security sectors – To ensure these sectors operate under effective scrutiny and accountability, civil society must be empowered to fulfil its role as critical observer in an independent, protected and effective manner. This includes the protection of civic space and ensuring public access to information, also in defence and security, with restrictions on the grounds of national security only applied on well-justified, exceptional circumstances. Additionally, whistleblowers and investigative journalists must be protected from retaliation, particularly when transparency serves the public interest over secrecy.

- Implement robust anti-corruption controls for arms transfers – Governments must conduct thorough corruption risk assessments for arms deals and ensure recipient countries uphold strong anti-corruption standards. Measures must be taken to prevent arms from being diverted and misused. (Read our briefing paper to learn more about how arms trade loopholes enabled crimes against humanity in Myanmar.)

Against the backdrop of heightened security risks, we call for ASEAN governments to prevent further risk for conflict and tensions through taking anti-corruption and its risks to defence, peace and security seriously, as well as to fully acknowledge the role of civil society in embarking on this vital endeavour for the region.

Notes to editors:

ASEAN Member States including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Myanmar feature in Transparency International Defence & Security’s 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI).

The Index scores and ranks countries based on the strength of their safeguards against defence and security corruption.

Malaysia and Indonesia appear in band ‘D’, indicating a ‘high’ risk of corruption, whereas Thailand appear in band ‘E’, indicating a ‘very high’ risk of corruption, and Myanmar in band ‘F’, indicating a ‘critical’ risk.

This toolkit is designed for advocates, activists and stakeholders engaged in advancing good governance and anti-corruption standards in the defence and security sectors, as well as advocates working in neighbouring agendas, like development, human rights and peace and security. It provides practical guidance, resources, and best practices to navigate the complexities of corruption in the defence and security sectors.

Users can utilise this toolkit as a comprehensive reference manual, with sections dedicated to understanding key concepts, planning advocacy strategies, and implementing actionable initiatives. It also covers topics such as security sector reform, corruption in arms trade, military spending, but also stakeholder engagement and advocacy tactics, aiming to empower users in advocating for robust governance and transparency in the sector.

Ara Marcen Naval examines how Venezuela’s military entrenchment in government and the economy undermines democracy and fuels corruption, and highlights the urgent need for transparency and civilian oversight.

Venezuela’s recent turmoil, marked by allegations of electoral fraud and widespread protests, reflects deeper systemic issues affecting the nation. These issues include evidence of rampant corruption, an overly militarised government, and the erosion of democratic principles.

The Venezuelan government’s adoption of a ‘civic-military’ model, has led to the military’s deep entrenchment in both political and economic spheres. This strategy not only ensures military loyalty through ideological indoctrination but also through substantial economic privileges. Consequently, the military’s influence extends far beyond traditional defence roles.

According to a 2021 report by Transparencia Venezuela, the Bolivarian National Armed Forces (FANB) hold significant positions in key sectors. Military personnel are present in the boards of at least 103 public companies and 11 out of 34 government ministries. Furthermore, 24 companies under the Ministry of Defence, mostly unrelated to military functions, highlight the extensive military footprint in non-defence areas.

There are risks associated with the military’s involvement in Venezuela’s economy. The military controls crucial sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture and food, which allows them to manipulate essential resources. This control is not only undemocratic but also breeds corruption and inefficiency.

Transparencia Venezuela reported an increase in the number of military personnel on public company boards from 2020 to 2021. However, this increased presence has not led to improved transparency or accountability. Many military-run enterprises operate with little public oversight, raising serious concerns about corruption and mismanagement. According to the Government Integrity Index, Venezuela faces critical corruption risks across its defence sector. Civilian democratic control of the military is extremely weak, and defence institutions are largely unaccountable to the public. Corruption is endemic throughout the sector. External scrutiny and institutional transparency are virtually non-existent, particularly concerning arms acquisitions and financial management. This lack of oversight exacerbates corruption and mismanagement issues, further undermining democratic governance and public trust.

The political power wielded by the military in Venezuela is equally concerning. Numerous former military officials occupy significant political roles, including governorships and mayoralties. The 2021 regional elections saw several ex-military figures elected, underscoring the military’s entrenched political influence.

Nicolás Maduro, the political successor of Chávez, has continued and deepened the militarisation of the government. During his tenure, a significant number of high-ranking government positions have been occupied by active or retired military officers, further consolidating military power within the state apparatus. The FANB has expanded its role in the economy and the management of the country’s strategic resources. In essence, the Venezuelan Armed Forces are closely tied to Chávez, Maduro, and their political project. This intertwining of military and political power creates a robust support system for the ruling regime. By placing military loyalists in key civilian roles, the regime secures a power base that is resistant to opposition and external pressures.

The Venezuelan government leverages its control over the armed forces to maintain ‘social peace’, which often means suppressing dissent and protests through force. The recent electoral fraud allegations have sparked significant public outcry, met with harsh responses from the government, calling the demonstrations ‘terrorists acts’ and sending the security forces to clash with upset citizens. This repression stifles democratic expression and perpetuates a cycle of fear and control.

The militarisation and corruption within the Venezuelan government have profound implications for democracy. The dominance of military power in political and economic spheres erodes democratic institutions and processes. Electoral fraud allegations are symptomatic of a broader decline in democratic norms, where elections are manipulated to maintain the status quo rather than reflect the will of the people.

While Venezuela finds its way out the current situation, hopefully moving towards democratic principles, there will need to find pathways to address these deep-rooted issues. First, enhancing transparency and accountability within military-run enterprises is crucial. Implementing robust anti-corruption measures and ensuring independent audits of military expenditures can help restore public trust.

Moreover, reducing the military’s role in civilian government functions is essential to strengthening democratic institutions. Encouraging civilian oversight of the military and promoting democratic norms can gradually diminish the military’s political influence. To get out of the current crisis, there is a need to improve the governance of the defence sector, and the military has a key role in the democratisation and accountability process.

April 9, 2024 – In the face of Haiti’s escalating crisis, marked by a surge in gang violence, a recent UN report underscores the critical need for an unwavering commitment to accountability and anti-corruption measures across public and defence sectors.

A UN Human Rights Office report calls for immediate and bold action to tackle the “cataclysmic” situation in Haiti.

In 2023, 4,451 people were killed and 1,668 injured due to gang violence. The number skyrocketed in the first three months of 2024, with 1,554 killed and 826 injured up to 22 March.

The report identifies key factors contributing to the crisis including an illicit economy incubated by corruption that facilitates the patronage of armed gangs by elites, and widespread corruption that contributed to the pervasive impunity in the country’s justice systems.

Responding to the worsening situation and intensified gang violence in Haiti, Sara Bandali, Director of International Engagement at Transparency International UK, said:

“We stand firmly with UN High Commissioner Volker Türk in making Haiti’s security crisis a top priority to protect its people and end the spiral of suffering.

“With gang violence and ‘self-defence brigades’ on the rise, and a government that is highly susceptible to corruption, the resurgence of private military security companies could also further destabilise the country.

“The urgency to confront the twin issues of corruption and governance failures is paramount. Accountability and anti-corruption efforts across public bodies and the defence & security sector are critical for the nation’s return to peace, stability, and security, and should never be traded off.”

Notes to editors:

Transparency International – Defence & Security previously warned about the destablising effects of private military security companies on Haiti following the assassination of the country’s president in 2021.

Our Hidden Costs report provides further detail on private military security companies and the risks they pose to fuelling corruption and conflict.

Photo by Heather Suggitt on Unsplash.

Transparency International Defence & Security’s (TI-DS) 2023-2025 Gender Mainstreaming Strategy aims to promote the capacity of the organisation to mainstream a gender perspective and move towards good and best practice approaches of gender-sensitivity and gender-responsiveness. Gender-sensitivity ensures that TI-DS programmes, projects and activities reduce the risk of harms to partners and participants and reduces risks of reproducing gender inequalities. Gender-responsiveness is more of a pro-active effort to challenge harmful gender norms at the root of corruption and its impacts. Both approaches require attention to gender at every stage of programme cycles, from deign to implementation and monitoring, evaluation and learning.

By Patrick Kwasi Brobbey (Research Project Manager), Léa Clamadieu and Irasema Guzman Orozco (Research Project Officers)

Corruption in defence and security heightens conflict risks, wastes public resources, and exacerbates human insecurity. It is crucial to recognise the gravity of corruption in the defence and security sector and develop institutional safeguards against it. Against this backdrop, Transparency International – Defence & Security (TI-DS) is launching the 2025 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) – the premier global measure of institutional resilience to corruption in the defence and security sector. This blog outlines what the GDI entails, its relevance, how it is produced, and essential information about the launch.

What is the GDI?

The GDI analyses institutional and informal controls to manage the risk of corruption in public defence and security establishments. The index focuses on five broad risk areas of defence: policymaking, finances, personnel management, operations, and procurement. To provide a broad and comprehensive reflection of these risk areas, the GDI assesses both legal frameworks and their implementation, as well as resources and outcomes.

Because of its focus, the index provides a framework of good practice that promotes accountable, transparent, and responsible governance in national defence establishments. The GDI is a critical tool in driving global defence reform and improving defence governance.

Previously dubbed the Government Defence Anti-corruption Index, the GDI was first released in 2013. Updated results were published in 2015, before the index went a major overhaul in 2020. The project now runs in a five-year cycle, so the new iteration will be published in 2025.

Gender: A New Dimension of the GDI

For the first time, the GDI will incorporate a gender approach. The 2024-2026 TI-DS Strategy acknowledges that corruption in the defence sector involves gendered power dynamics that produce different impacts, perceptions, risks, forms of corruption, and experiences for diverse groups of women, men, girls, boys, and sexual and gender minorities. In alignment with the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda, many defence and security institutions now recognise gender. Nevertheless, their efforts mainly focus on achieving gender balance, mainstreaming, and representation. There is a lack of visibility on gendered corruption risks in the defence and security policy agenda, as anti-corruption measures and gender concerns are often addressed separately.

Consistent with our commitment to addressing this, the 2025 GDI adopts a gender perspective to assess the gender dimensions of corruption risks in this sector. For this iteration, gender indicators have been developed and will be piloted. The gendered corruption risk indicators cover four cross-cutting themes: legal and normative commitments, gender balance strategies, gender mainstreaming strategies, and prevention and response to gender-based violence.

Integrating gender into corruption risk assessments like the GDI can help produce gendered anti-corruption interventions that recalibrate uneven power relations affecting people of diverse genders and minority groups. Additionally, it will help to identify evidence-based best practices in the gender, anti-corruption, and security space.

Why is the GDI important?

The GDI offers an evidence-based approach which emphasises that better institutional controls reduce the risk of corruption. It constitutes a comprehensive assessment of integrity matters in the defence sector and plays a crucial role in driving global defence reform, thereby improving defence governance.

The relevance of the index is enshrined in the rationale for creating it. The GDI recognises that:

- Corruption within the defence and security sector impede states’ ability to defend themselves and provide the needed security for their citizens. For instance, in Iraq in 2014, 50,000 ‘ghost soldiers’ were found in the budget – soldiers that existed only on paper and whose salaries were stolen by senior or high-ranking officers. The Iraqi forces were left depleted, unprepared to face real threats and unable to protect citizens and provide national security.

- The secrecy of the defence sector contributes to the wastage of resources and the weakening of public institutions, facilitating the personalisation/privatisation of public resources for private gains via defence establishments. According to the 2020 GDI, 37% of states in the index had limited to no transparency on procurements.

- Efficacious public institutions and informal mechanisms are central in preventing the wastage of state funds, the misappropriation of power, and the development of graft in the defence and security sector. In 2023, it was revealed that the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence was planning to overpay suppliers for food intended for troops. This led to official investigations and ultimately saw the auditions in the Ukrainian parliament pass legislation that enhances transparency in defence procurement.

These examples underscore the importance and timeliness of the GDI in rooting out corruption in national defence and security sectors.

How is the GDI created?

The GDI consists of questions broken down into indicators spanning the five corruption risks. These serve as the basis of data collection in countries carefully selected using the TI-DS selection criteria, which predominantly centre on the susceptibility of a country’s defence institutions to corruption. These countries will be drawn from the following TI regions: sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia Pacific and South Asia, and Western Europe and North America.

TI-DS uses a rigorous methodology consisting of an independent Country Assessor conducting research and providing an original, context-specific data that is accurate and verifiable. The data are then first extensively reviewed by a TI-DS team of topical and methodology experts before being sent to external reviewers (specifically, peer reviewers and relevant TI national chapters and governments) for additional quality checks. As part of its commitment to transparency, TI-DS has published the GDI Methods Paper that outlines the methodological and analytical considerations and choices .

Overview of the Launch

The 2025 GDI research project, which will be conducted in six waves representing the TI regions, began on Tuesday 26 March 2023. A webinar was organised for TI national chapters whose countries are in the first wave. This information session ensured mutual learning between TI-DS and the chapters. Other webinars will be organised later for chapters whose countries are in the subsequent waves.

TI-DS has secured ample funding for the sub-Saharan African wave of the 2025 GDI. However, as the GDI is of utmost importance and requires timely execution, we are working towards securing additional funding to cover the administrative and operational costs of the remaining five waves. TI-DS invites the stakeholders to get in touch via gdi@transparency.org to help support the remaining waves. Thank you.

March 28, 2024 – Transparency International – Defence & Security (TI-DS) is excited to announce the start of work on the next iteration of the Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), the leading global benchmark of corruption risks in the defence and security sector.

The GDI 2025 is TI-DS’s flagship research product and follows on from the GDI 2020. This latest iteration includes expert assessments of around 90 countries as well as the introduction of a gender perspective, recognising the nuanced impacts of corruption across different gender and underrepresented groups.

The GDI provides a framework of good practice that promotes accountable, transparent, and responsible governance in the defence & security sector. It is a useful tool for civil society to collaborate with Ministries of Defence, the armed forces, and with oversight institutions, to build their capacity in advocating for transparency and integrity.

Countries are evaluated by independent assessors who assess the strength of anti-corruption safeguards and institutional resilience to corruption in five key areas:

- Financial: includes strength of safeguards around military asset disposals, whether a country allows military-owned businesses, and whether the full extent of military spending is publicly disclosed.

- Operational: includes corruption risk in a country’s military deployments overseas and the use of private security companies.

- Personnel: includes how resilient defence sector payroll, promotions and appointments are to corruption, and the strength of safeguards against corruption to avoid conscription or recruitment.

- Political: includes transparency over defence & security policy, openness in defence budgets, and strength of anti-corruption checks surrounding arms exports.

- Procurement: includes corruption risk around tenders and how contracts are awarded, the use of agents/brokers as middlemen in procurement, and assessment of how vulnerable a country is to corruption in offset contracts.

These independent assessments go through multiple layers of expert review before each country is assigned an overall score and rank. This makes the GDI extremely rigorous in its methodology.

The amount of work required to produce the GDI means the new country results will be released in six waves:

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Middle East and North Africa

- Central and Eastern Europe

- Latin America

- Asia Pacific and South Asia

- Western Europe and North America

The first wave is provisionally due to be published in early 2025.

Notes:

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI), with results published in 2013 and 2015. The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. The 2025 results can be compared with those from 2020 to get a picture of global trends in defence governance, and which countries are improving.

The GDI is a corruption risk assessment of the defence and security sector within a country, which assesses the quality of mechanisms used to manage corruption risk –and evaluating the factors that are understood to facilitate corruption.

It is not a measurement of corruption and does not measure the amount of funds that are lost to corruption, identify corrupt actors, or estimate the perceptions of corruption in the defence & security sectors by the public.

TI-DS has secured funding for the sub-Saharan African wave and is working towards securing additional support to cover the costs of producing the remaining five waves. We invite all stakeholders, including public agencies, multilateral organisations and INGOs, to get in touch via gdi@transparency.org to help support the remaining waves.

February 15, 2024 – As African leaders gather in Addis Ababa for the 2024 African Union (AU) Summit, the urgent agenda of addressing peace and security takes centre stage.

While ensuring the safety of citizens remains the primary obligation of governments, many African countries grapple with persistent conflicts and an alarming recurrence of coups. Internal conflicts, often fuelled by the illicit arms trade and the unlawful exploitation of natural resources, has threatened the stability of several countries on the continent.

Corruption has served as a catalyst for conflicts in Burkina Faso, Sudan, Mali, Nigeria and the Central African Republic, which has poured fuel on the flames of grievances against political leaders and incited violent upheavals.

By eroding public trust and undermining the effectiveness of defence and security institutions, corruption has eroded the rule of law and perpetuated instability. This has led to diminished access to essential services for many and fostered environments conducive to human rights abuses. There is a pressing need to recognise corruption as a security threat in itself and prioritise anti-corruption efforts within security sector reform and governance (SSR/G).

It is imperative that AU members unite in addressing corruption within defence and security sectors as a crucial step toward achieving conflict resolution, peace, stability, and security goals.

Transparency International Defence & Security calls on states to:

- Recognise corruption in defence as a security threat: Governments must acknowledge the threat of corruption to national security and allocate resources accordingly.

- Empower civilian oversight: Governments should encourage active citizen participation in oversight to enhance transparency and accountability.

- Integrate anti-corruption in peace efforts and SSR: Embed anti-corruption measures into conflict resolution, peacebuilding and security sector reform agendas for more resilient societies.

Peace and stability in Africa and around the world cannot be safeguarded without making the efforts to address the insidious threat of corruption proportionate to the threat which it represents.

The deposed Niger government’s efforts fighting corruption contrast markedly with the neglect shown in neighbouring Burkina Faso ahead of the previous coups which rocked the region. Transparency International Defence and Security’s Mohamed Bennour, Michael Ofori-Mensah and Denitsa Zhelyazkova compare the collapse of the two nations and show how ECOWAS can reinforce democracy in the region.

Upon his election as chair of the West African regional bloc ECOWAS last month, Nigeria’s new president Bola Tinubu made plain his intentions to champion democracy in efforts to arrest the spate of military uprisings that have disrupted the region in recent years.

It wasn’t long however before another arrived, this time in Niger. ECOWAS swiftly threatened military intervention. ECOWAS and other power brokers traditionally tend to respond to events of this kind with talk of zero tolerance and sanctions – tough words but sentiment that, too often, is accompanied by minimal analysis of the root causes.

Transparency International in Niger are among the civil society groups that have observed a trend leading to coups in their country: the discovery of lucrative natural resources. In November, the Niger-Benin pipeline, the largest in Africa, is due to start exporting crude petroleum for the first time. This will multiply Niger’s crude exports by five, with an expected GDP increase of 24 per cent. Before this, the discovery of uranium in 1974 coincided with the overthrow of Niger’s leadership. Then an oil boom in 2010 was swiftly followed by another coup.

The resources vary but the outcomes follow a pattern.

The removal of Niger’s president Mohamed Bazoum has been lamented by our colleagues on the ground. This is because he had been showing willingness to step up to the long-ignored challenge of confronting corruption in the country.

Supporters of Bazoum protested in the street against the coup, together with CSOs and unions. Some have expressed their scepticism about the military being able to solve the governance challenges and issues of insecurity faced in the country.

The scepticism is driven by the fact that Niger’s security had been progressing better than in neighbouring countries, with fewer terror fatalities than those recorded in Mali and Burkina Faso.

There have been counter protests in Niger. Yet Bazoum had only been in power for two years. ANLC, (Transparency International’s chapter in Niger) had enjoyed political support from the president and parliament for the adoption of an anti-corruption law, central to addressing risks in defence and security and other sectors. This law, if and when implemented, will protect informants, witnesses, experts and whistleblowers. It will also criminalise bad practices common in Niger, such as the over-invoicing of public contracts and refusing to declare assets of civil and military figures.

Contrasting situation in Burkina Faso – decline and lost trust

The strides that had been made in Niger contrast with the decline seen in Burkina Faso, which until last week had been the nation that had suffered a coup most recently. There, a failure to secure enough resources for the army put paid to its elected leaders. Endemic corruption within the security forces contributed to the eroding of the perceived legitimacy of authorities. Public trust in government was lost. Several reports from Transparency International Defence and Security have shown how this creates dynamics for the expansion of non-state and extremist groups.

Corruption is not a victimless crime. In April, 44 civilians were killed by terrorist groups in north-eastern Burkina Faso. Later that month, a further 60 were killed by men in national military uniform in the northern village of Karma.

Ironically, Burkina Faso was considered immune to the regional spread of violence until relatively recently. Almost overnight, the land-locked state found itself a focal point in the expansion strategies of various extremist groups when a Romanian citizen was abducted in Tambao on Burkina Faso’s north-east border with Mali and Niger in 2015.

Ever since, terrorist groups, including the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), and the Burkinabe-founded Ansarul Islam have been exploiting an unresolved socio-economic crisis amid endemic corruption.

At a summit in February, the African Union announced that Burkina Faso and Mali will remain suspended from the continental bloc. Adding more pressure to the countries’ leadership, ECOWAS also extended existing sanctions on both countries, “reaffirming zero tolerance against unconstitutional change of government“.

Sanctions can be a useful tool. They deliver a clear stance against illegal and undemocratic change of power. However they do not offer lasting solutions to some of the core issues behind the takeovers. And they can risk exacerbating grievances and harming the most vulnerable groups.

In order to build a democratic and secure future in Burkina Faso, corruption in the defence sector must be tackled. There must be a focus on pragmatic reforms to ensure, and safeguard, transparency, accountability and efficacy. And civil society must be involved in the process. Our Government Defence Integrity Index provides evidence supporting arguments that the more open to civil participation and transparent a government is, the higher the level of institutional resilience to corruption.

Until last month, Niger had what Burkina has needed. National civil society was engaged with both government and the military, working for greater transparency and tackling defence sector corruption.

Now, our colleagues in Niger have called for “the immediate restoration of a civil regime supported by inclusive governance and the preservation of civic space. These measures are essential to maintain the principles of transparency and accountability that we defend.”

Not for the first time, as the international community scrambles to respond to events in the country, and watches as they continue to unfold, we have been reminded that corruption is a fundamental threat to security. Access to and control over natural resources drives power struggles that extend beyond country borders. Only driving out corruption will suffice to break the cycle for all those suffering in the Sahel.

Responding to reports of corruption in Ukraine military recruitment centres, Josie Stewart, Director of Transparency International Defence and Security, said:

Reports of “unfit to serve” certificates being sold from Ukraine’s regional military recruitment centres demonstrate once again how corruption can potentially undermine military systems.

This case affirms the role free media can play in holding officials to account while it has been good to see swift action taken by the government since the findings were published.

In contrast to the corruption-related problems that have plagued the effectiveness of Russia’s Army from the start, Ukraine has invested in improving oversight and accountability.

Ukraine is continuing to fight corruption at the same time as fighting on the battlefield. With the stakes this high, they know they must win on both fronts.

press@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

Out of hours – Weekends; Weekdays (UK 17.30-21.30): +44 (0)79 6456 0340