Theme: Personnel

By Leah Pickering, Programme Officer – Transparency International Defence & Security

“Trick or treat?”

It’s a familiar call every 31 October. But twenty-five years ago, another call echoed through the corridors of the United Nations in New York. An active and vibrant civil society movement, joined by a handful of determined member states, were demanding something far more profound: power, protection, participation, peace, and security.

For years, these advocates had been knocking on closed doors, urging the UN to confront the gendered realities of conflict and the exclusion of women from decision-making. At last, the door opened.

On 31 October 2000, the Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS), a landmark decision that recognised both the unique security challenges faced by women in conflict and their crucial contributions to peace. Centred on the four pillars of participation, protection, prevention, and relief and recovery, it called for women’s full inclusion in peace and political processes, stronger measures to prevent and respond to gender-based violence, and the advancement of gender equality across all peace and security efforts.

It was a historic shift from seeing women as passive victims of war to recognising them as active agents of peace and positive change. In the years that followed, more than ten additional resolutions expanded this vision, and over one hundred countries developed National Action Plans to bring it to life. Regional organisations such as the African Union, the European Union, and NATO integrated WPS principles into their frameworks, helping to embed gender perspectives across peace and security institutions.

Yet even amid these gains, not all doors have opened equally. Women continue to be underrepresented in peace negotiations, and when they do participate, their involvement is often symbolic rather than substantive. Implementation has frequently ignored the perspectives of women from the Global South, LGBTIQ+ individuals, and other marginalised groups, leaving significant voices unheard. The spaces where women’s rights organisations once influenced and defended the agenda are shrinking, and those most affected by conflict and violence are often the first to be excluded.

No tricks, just truth: while the WPS agenda has achieved much, persistent gaps and blind spots continue to undermine its promise.

One of the most concerning of these gaps is corruption.

Corruption impacts every pillar of the WPS framework, silently shaping whose voices are heard, whose rights are protected, and who remains unsafe. In defence and security sectors, corruption manifests in deeply gendered ways such as sexual extortion in exchange for aid or safety, bribery that denies survivors justice, and patronage networks that exclude women and marginalised communities from decision-making. These are not small flaws in governance. They are daily realities that determine who is safe, who is heard, and who gets justice.

In fragile and conflict-affected settings, corruption and gender-based violence feed off each other. From peacekeepers implicated in sexual exploitation and abuse, to officials colluding with traffickers, to survivors silenced by corrupt courts, the pattern is disturbingly familiar. Corruption weakens institutions, insecurity rises, gender-based violence spreads, and impunity deepens. The result is a vicious cycle that corrodes both peace and trust.

Despite these harms, corruption has remained a persistent threat. The WPS and anti-corruption agendas have developed in isolation, speaking different policy languages, working through different systems, and drawing on different funding streams. Corruption is often treated as a technical problem of governance, while WPS is seen as a political and human one. The result is a blind spot that allows abuse and insecurity to persist unchecked.

Twenty-five years after its adoption, the WPS agenda must face the truth: corruption continues to undermine its promise of peace and equality. Transparency International Defence and Security’s new policy brief, Closing the Blind Spot: Confronting Corruption to Advance Women, Peace and Security, argues that integrating anti-corruption into the WPS agenda is not an optional extra – it is essential. Recognising corruption as a driver of gendered insecurity is vital if prevention, protection, participation, and recovery are to be realised in practice rather than only in principle.

The brief calls for five key steps:

- Acknowledge the risk by naming sexualised corruption explicitly in WPS frameworks.

- Assess with a gender lens by embedding gender-sensitive corruption risk assessments into security sector reform, disarmament, demobilisation, reintegration, and peacekeeping processes.

- Embed safeguards through survivor-safe oversight and reporting mechanisms.

- Enable accountability by empowering parliaments, national human rights institutions, and civil society watchdogs.

- Align global tools by connecting WPS, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and United Nations Convention Against Corruption obligations into a coherent framework for integrity and inclusion.

Twenty-five years after UNSCR 1325 first opened the door, the WPS agenda still inspires hope. Yet it also demands honesty. If we are to move from promise to practice, we must unmask corruption and confront the structures that keep women, girls and LGBTQI+ individuals unsafe.

No tricks, just truth: peace that ignores corruption will always be haunted by inequality, insecurity, and silence.

It is time to face the ghosts and build peace that is not only promised but practiced.

Civil war has been raging in Sudan for soon two years with no end in sight. Its violence and destruction have caused a “humanitarian catastrophe”. Yet, as the conflict remains at the margins of media and public attention, so does one of its main drivers: corruption.

Weak defence governance and failed security sector reforms have played an important role in driving the conflict. Over the last six years, Sudan has experienced high levels of political instability, writes Emily Wegener.

Whether as a driver of the protests in 2018-2019 that forced President Omar al-Bashir out of power, or a as contributing factor to the October 2021 military coup staged by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that halted the democratic transition process, corruption continuously contributed to this volatility. Regimes fell, but the power structures and the corruption networks in and around the military and security forces survived. These networks then fuelled tensions between the SAF and RSF, which reached their breaking point in April 2023 with the outbreak of armed conflict between the two groups.

From the onset of the conflict, corruption has driven the violence. Failure to agree on a way forward in the country’s security sector reform (SSR) – the process of improving a country’s police, military and related institutions to ensure they are effective, accountable and respect human rights – is widely seen as one of the key reasons for why the democratic transition failed. Placing the RSF under civilian control and enhancing democratic scrutiny of the SAF were two of the most contentious questions in the SSR process.

But what made improving the oversight and accountability of these groups so contentious? Our 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) assessed the corruption risk as critical throughout Sudan’s defence institutions, concluding that “corruption is widespread in the sector and there are virtually no anti-corruption mechanisms”. Civilian democratic control and external oversight of defence institutions were also found to be non-existent.

An absence of accountability enabled both the SAF and the RSF to repurpose the state’s defence and security institutions to enrich high-ranking security officials and create an economy dominated by military interests. Companies owned by SAF officials have long controlled lucrative private sectors, from telecommunications to meat processing, to the detriment of public investment and sustainable economic growth. Meanwhile, the RSF controls most of the country’s gold trade – a significant income stream, considering that Sudan was the third-largest gold-producer on the continent in 2023. By the time the war broke out, the RSF owned around 50 companies, acquired largely by reinvesting the profits from gold trade into other industries. Transition to civilian rule would have meant placing the SAF under civilian oversight; for the RSF, integration into the army. When the RSF was not ready to give up its advantages, or accept this level of accountability, it declared war.

Why we produced ‘Chaos Unchained’

In February 2025, nearly two years the outbreak of the war, Sudan is facing starvation and the world’s largest displacement crisis. An estimated 30% of the population, over 11 million people, have been forced to leave their homes. According to the UN Secretary General’s latest report, over 25 million people live in food insecurity, including over 750,000 people living in conditions comparable to famine, as defined by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). Both sides, and the RSF in particular, are reported to have perpetrated ethnic cleansing and sexual violence.

Yet, the attention paid to the conflict is scarce. Sudan rarely makes the headlines. Across the international community, the focus is elsewhere. To shed light on this ‘forgotten conflict’ and its drivers, we have produced a 10-minute video looking at the origins of Sudan’s turmoil. Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan examines how corruption, kleptocratic plunder of the country’s resources and lax enforcement of arms embargoes have contributed to the ongoing conflict and the humanitarian catastrophe that comes with it.

Possible solutions

Governments and private actors can take steps to reduce the role of corruption in prolonging the fighting, and to limit the chance of relapse after a political solution is negotiated.

At international level, the UN, the EU and their Member States can:

- Recognise the links between corruption in the defence and security sector and the violence and elevate the importance of addressing corruption in the conflict resolution agenda. A strong precedent is the UN Security Council Resolution 2731/2024 on the situation in South Sudan, where the Council recognises that “intercommunal violence in South Sudan is politically and economically linked to national-level violence and corruption”, and stresses the need of effective anti-corruption structures to ensure and finance the political transition and humanitarian needs of the population.

- Explore the links between arms diversion and corruption, and the resulting circumvention of UN arms embargo and human rights abuses in the Darfur region. Existing mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Sudan and the Security Council’s Panel of Experts can contribute to improving the evidence base on the role of corruption, especially in the defence and security sectors, in fuelling the war and humanitarian crisis.

- Prioritise strengthening the rule of law and anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding. Placing the SAF and the RSF and their economic assets and activities under civilian oversight is a key step toward transparent and accountable defence and security forces. A long-term, transformative, and inclusive SSR process will be the most necessary but also the most contentious element of any negotiated solution to the conflict in Sudan. Additionally, any peacekeeping or peacebuilding interventions will need to firmly prioritise anti-corruption as a conflict prevention measure.

At national level, the governments of arms exporting countries can:

- Strengthen arms export policies and implementation guidelines. Foreign-made weapons and military equipment are being diverted into Darfur despite a long-standing UN Security Council arms embargo. Arms exporting countries can use our GDI to better assess the risk of corruption in defence institutions. Robust corruption risk assessments can help to curb diversion risks in arms sales to Sudan and the regional partners of the SAF and the RSF.

- Better regulate defence offsets. In connection with major arms sales, defence companies often negotiate lucrative offset packages with even less transparency than the arms sales. Our research has shown that defence company offsets can contribute to fuelling conflict dynamics, including in countries like Sudan by supporting industries in the UAE that help finance Sudanese armed actors. Enhancing internal and external transparency and oversight around these deals can mitigate risks of contributing to natural resource laundering for armed groups and fuelling conflict dynamics such as the one in Sudan.

Sudan shows that fighting corruption is not separate from discussions on ceasefires, political negotiations and peace processes. Integrating anti-corruption measures and fostering transparency and accountability in Sudan’s defence and security sector is key to the long-term success of any negotiated political solution.

You can watch Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan here.

Register here to join our webinar on Thursday, 6 February, in which we discuss the root causes of the conflict and pathways to peace with an expert panel.

Corruption undermines the legitimacy and effectiveness of government institutions in all sectors, but it thrives in areas where large budgets intersect with high levels of secrecy and limited accountability, write Michael Ofori-Mensah, Denitsa Zhelyazkova and Harvey Gavin.

The defence and security sector features all these risk areas, making it particularly vulnerable. The combination of secrecy, limited oversight and, often, high levels of discretionary power in decision-making, creates an environment ripe for corruption. This vulnerability not only undermines the ability of governments to fulfil their primary duty to their citizens of keeping them safe, it also undermines their legitimacy.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is working to address this issue. A key contribution is our recent involvement in NATO’s Building Integrity Institutional Enhancement Course. This program focuses on supporting national governments with capacity building in developing Integrity Action Plans aimed at strengthening the integrity of their defence institutions. Before drawing up these plans, defence officials must identify areas most at risk of corruption. This is where the recent enhancement aimed at improving accessibility and use of our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) becomes an invaluable diagnostic tool.

The GDI is the world’s leading assessment of corruption risks in national defence institutions. As a corruption risk assessment tool, it examines the quality of institutional controls to manage the risk of corruption in nearly 90 countries around the world on both policymaking and public sector governance and covers five major risk areas:

- Financial: includes strength of safeguards around military asset disposals, whether a country allows military-owned businesses, and whether the full extent of military spending is publicly disclosed.

- Operational: includes corruption risk in a country’s military deployments overseas and the use of private security companies.

- Personnel: includes how resilient defence sector payroll, promotions and appointments are to corruption, and the strength of safeguards against corruption to avoid conscription or recruitment.

- Political: includes transparency over defence & security policy, openness in defence budgets, and strength of anti-corruption checks surrounding arms exports.

- Procurement: includes corruption risk around tenders and how contracts are awarded, the use of agents/brokers as middlemen in procurement, and assessment of how vulnerable a country is to corruption in offset contracts.

Within these areas, the GDI identifies 29 specific corruption risks, assessed through 77 main questions and 212 underlying indicators. These indicators examine both legal frameworks and their implementation, as well as the allocation of resources and outcomes.

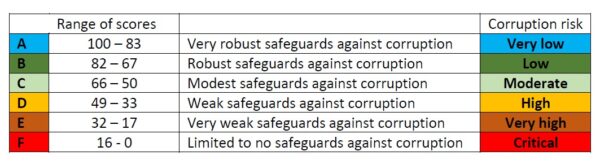

It, therefore, provides defence institutions with a comprehensive assessment of corruption vulnerabilities and a platform to identify safeguards against corruption risks. Each indicator is scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with aggregated scores determining the strength of a country’s institutional practices and protocols to manage corruption risks in defence,: from A (low corruption risk/very robust institutional resilience to corruption) to F (high corruption risk/limited to no institutional resilience to corruption).

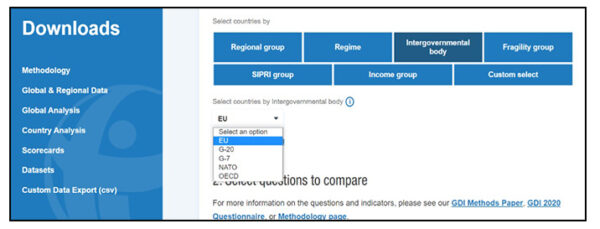

Our recent updates to the GDI website have significantly improved its functionality, allowing users to group countries by various categories such as region, income level, regime type, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) group and intergovernmental body affiliation. For example, policymakers seeking to understand problematic areas within the EU defence sector can now explore specific indicators of interest and export the data for detailed analysis.

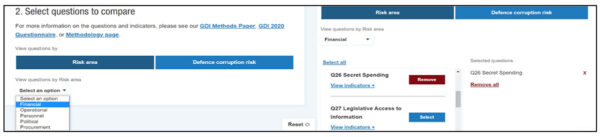

The enhancement also provides a functionality that enables comparisons across the 77 main questions of the GDI thus facilitating targeted assessments of particular risk areas and cross-country analysis.

Data from the GDI, both quantitative and qualitative, can be downloaded in .csv format, compatible with numerous data processing tools like Excel, SPSS, and Access. This feature allows users to generate customised spreadsheets containing only the information pertinent to their needs. The qualitative data, derived from expert assessor interviews, provides critical insights that complement the quantitative scores, offering a nuanced understanding of corruption risks.

(Note: these updates apply to the current 2020 iteration of the GDI. Our team is working on the 2025 GDI – you can find more information about it here)

The ongoing challenges posed by corruption in the defence sector demand sustained and coordinated efforts from both national governments and the international community. Initiatives like NATO’s Building Integrity Institutional Enhancement Course, supported by tools like the GDI, represent significant strides toward fostering good governance in defence institutions. But maintaining high standards of defence governance remains an ongoing challenge that requires vigilance and commitment.

Reforms are urgently needed to address the institutional gaps identified by the GDI. Integrity Action Plans, informed by comprehensive corruption risk assessments, are essential for guiding these changes. By prioritising transparency, accountability and resilience, countries can strengthen their defence institutions, reduce corruption and improve peace and security.

The Geneva Peace Week (GPW) is one of the important appointments on the international peacebuilding calendar, writes Francesca Grandi, our Senior Advocacy Expert. This year, it centred around the question: “What is Peace?”

A call to action and an opportunity for reflection, the forum brought together a wide array of stakeholders from the peace and security ecosystem and beyond, highlighting the cross-cutting nature of peacebuilding and the need for innovative and collaborative solutions for building lasting peace.

Building bridges

Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) attended GPW 2024 to make the case for recognising corruption in the defence and security sectors as a key driver of violence and armed conflict, and to advocate for a more comprehensive and systematic inclusion anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding frameworks. We introduced our research and engaged with many panels. Colleagues in international NGOs, UN bodies, and Member States expressed a genuine interest in our work and acknowledged the importance of addressing corruption in the defence and security sector to build trust and resilience in fragile contexts. It was clear that more research and practical tools are needed to bridge what we know about corruption and armed conflict.

Anti-corruption as a preventive tool

In nearly every session, the themes of prevention, trust-building, and institutional resilience resonated strongly with our message that anti-corruption contributes to postive peace and security outcomes and provides a relevant lens across a wide range of peace and security issues.

Corruption hampers the effectiveness of security sector reforms, arms controls, and truth and reconciliation processes; it undermines the protection and promotion of human rights; it erodes trust between former combatants and government institutions, and thus the successful reintegration of ex-combatants, increasing the likelihood of conflict relapse.

We asked whether corruption is sufficiently integrated into international peace frameworks, such as the UN Pact for the Future. While some peacekeeping mandates include anti-corruption provisions, the absence of explicit references in key documents remains a concerning omission.

By addressing corruption as a root cause of conflict and ensuring that public resources are used as intended, we can build more resilient and inclusive societies and enhance the impact of localised and gender-responsive peacebuilding approaches. By integrating anti-corruption strategies in our peace responses, we can strengthen institutional integrity and help foster the public trust and the institutional resilience needed for lasting peace.

Next steps: Expanding partnerships and advocating

Moving forward, TI-DS remains committed to advocating for integrating anti-corruption as a key component of the global peace and security agenda and for including corruption prevention strategies in future peace interventions, emphasising their role in strengthening governance and peace processes.

As we continue our advocacy efforts, our focus remains on building partnerships, producing evidence-based research, and ensuring that anti-corruption remains at the forefront of global peace and security discussions. The GPW provided us with a platform to advance these objectives, and we look forward to furthering our work in this vital space.

This toolkit is designed for advocates, activists and stakeholders engaged in advancing good governance and anti-corruption standards in the defence and security sectors, as well as advocates working in neighbouring agendas, like development, human rights and peace and security. It provides practical guidance, resources, and best practices to navigate the complexities of corruption in the defence and security sectors.

Users can utilise this toolkit as a comprehensive reference manual, with sections dedicated to understanding key concepts, planning advocacy strategies, and implementing actionable initiatives. It also covers topics such as security sector reform, corruption in arms trade, military spending, but also stakeholder engagement and advocacy tactics, aiming to empower users in advocating for robust governance and transparency in the sector.

In this briefing, we showcase the experiences of people whose lives have been torn apart by corruption within the defence and security sector. Their stories are gathered from across the world, drawn from first-hand conversations with those willing to give testament, and from investigations conducted by media and international organisations.

These stories demonstrate how institutional weaknesses, gaps in oversight, systematic abuses of power, and lack of accountability within defence and security institutions have a disastrous impact on people’s lives. We make the case for some of the key systemic steps needed to address the risk of corruption in these sectors.

April 9, 2024 – In the face of Haiti’s escalating crisis, marked by a surge in gang violence, a recent UN report underscores the critical need for an unwavering commitment to accountability and anti-corruption measures across public and defence sectors.

A UN Human Rights Office report calls for immediate and bold action to tackle the “cataclysmic” situation in Haiti.

In 2023, 4,451 people were killed and 1,668 injured due to gang violence. The number skyrocketed in the first three months of 2024, with 1,554 killed and 826 injured up to 22 March.

The report identifies key factors contributing to the crisis including an illicit economy incubated by corruption that facilitates the patronage of armed gangs by elites, and widespread corruption that contributed to the pervasive impunity in the country’s justice systems.

Responding to the worsening situation and intensified gang violence in Haiti, Sara Bandali, Director of International Engagement at Transparency International UK, said:

“We stand firmly with UN High Commissioner Volker Türk in making Haiti’s security crisis a top priority to protect its people and end the spiral of suffering.

“With gang violence and ‘self-defence brigades’ on the rise, and a government that is highly susceptible to corruption, the resurgence of private military security companies could also further destabilise the country.

“The urgency to confront the twin issues of corruption and governance failures is paramount. Accountability and anti-corruption efforts across public bodies and the defence & security sector are critical for the nation’s return to peace, stability, and security, and should never be traded off.”

Notes to editors:

Transparency International – Defence & Security previously warned about the destablising effects of private military security companies on Haiti following the assassination of the country’s president in 2021.

Our Hidden Costs report provides further detail on private military security companies and the risks they pose to fuelling corruption and conflict.

Photo by Heather Suggitt on Unsplash.

Transparency International Defence & Security’s (TI-DS) 2023-2025 Gender Mainstreaming Strategy aims to promote the capacity of the organisation to mainstream a gender perspective and move towards good and best practice approaches of gender-sensitivity and gender-responsiveness. Gender-sensitivity ensures that TI-DS programmes, projects and activities reduce the risk of harms to partners and participants and reduces risks of reproducing gender inequalities. Gender-responsiveness is more of a pro-active effort to challenge harmful gender norms at the root of corruption and its impacts. Both approaches require attention to gender at every stage of programme cycles, from deign to implementation and monitoring, evaluation and learning.

By Patrick Kwasi Brobbey (Research Project Manager), Léa Clamadieu and Irasema Guzman Orozco (Research Project Officers)

Corruption in defence and security heightens conflict risks, wastes public resources, and exacerbates human insecurity. It is crucial to recognise the gravity of corruption in the defence and security sector and develop institutional safeguards against it. Against this backdrop, Transparency International – Defence & Security (TI-DS) is launching the 2025 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) – the premier global measure of institutional resilience to corruption in the defence and security sector. This blog outlines what the GDI entails, its relevance, how it is produced, and essential information about the launch.

What is the GDI?

The GDI analyses institutional and informal controls to manage the risk of corruption in public defence and security establishments. The index focuses on five broad risk areas of defence: policymaking, finances, personnel management, operations, and procurement. To provide a broad and comprehensive reflection of these risk areas, the GDI assesses both legal frameworks and their implementation, as well as resources and outcomes.

Because of its focus, the index provides a framework of good practice that promotes accountable, transparent, and responsible governance in national defence establishments. The GDI is a critical tool in driving global defence reform and improving defence governance.

Previously dubbed the Government Defence Anti-corruption Index, the GDI was first released in 2013. Updated results were published in 2015, before the index went a major overhaul in 2020. The project now runs in a five-year cycle, so the new iteration will be published in 2025.

Gender: A New Dimension of the GDI

For the first time, the GDI will incorporate a gender approach. The 2024-2026 TI-DS Strategy acknowledges that corruption in the defence sector involves gendered power dynamics that produce different impacts, perceptions, risks, forms of corruption, and experiences for diverse groups of women, men, girls, boys, and sexual and gender minorities. In alignment with the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda, many defence and security institutions now recognise gender. Nevertheless, their efforts mainly focus on achieving gender balance, mainstreaming, and representation. There is a lack of visibility on gendered corruption risks in the defence and security policy agenda, as anti-corruption measures and gender concerns are often addressed separately.

Consistent with our commitment to addressing this, the 2025 GDI adopts a gender perspective to assess the gender dimensions of corruption risks in this sector. For this iteration, gender indicators have been developed and will be piloted. The gendered corruption risk indicators cover four cross-cutting themes: legal and normative commitments, gender balance strategies, gender mainstreaming strategies, and prevention and response to gender-based violence.

Integrating gender into corruption risk assessments like the GDI can help produce gendered anti-corruption interventions that recalibrate uneven power relations affecting people of diverse genders and minority groups. Additionally, it will help to identify evidence-based best practices in the gender, anti-corruption, and security space.

Why is the GDI important?

The GDI offers an evidence-based approach which emphasises that better institutional controls reduce the risk of corruption. It constitutes a comprehensive assessment of integrity matters in the defence sector and plays a crucial role in driving global defence reform, thereby improving defence governance.

The relevance of the index is enshrined in the rationale for creating it. The GDI recognises that:

- Corruption within the defence and security sector impede states’ ability to defend themselves and provide the needed security for their citizens. For instance, in Iraq in 2014, 50,000 ‘ghost soldiers’ were found in the budget – soldiers that existed only on paper and whose salaries were stolen by senior or high-ranking officers. The Iraqi forces were left depleted, unprepared to face real threats and unable to protect citizens and provide national security.

- The secrecy of the defence sector contributes to the wastage of resources and the weakening of public institutions, facilitating the personalisation/privatisation of public resources for private gains via defence establishments. According to the 2020 GDI, 37% of states in the index had limited to no transparency on procurements.

- Efficacious public institutions and informal mechanisms are central in preventing the wastage of state funds, the misappropriation of power, and the development of graft in the defence and security sector. In 2023, it was revealed that the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence was planning to overpay suppliers for food intended for troops. This led to official investigations and ultimately saw the auditions in the Ukrainian parliament pass legislation that enhances transparency in defence procurement.

These examples underscore the importance and timeliness of the GDI in rooting out corruption in national defence and security sectors.

How is the GDI created?

The GDI consists of questions broken down into indicators spanning the five corruption risks. These serve as the basis of data collection in countries carefully selected using the TI-DS selection criteria, which predominantly centre on the susceptibility of a country’s defence institutions to corruption. These countries will be drawn from the following TI regions: sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia Pacific and South Asia, and Western Europe and North America.

TI-DS uses a rigorous methodology consisting of an independent Country Assessor conducting research and providing an original, context-specific data that is accurate and verifiable. The data are then first extensively reviewed by a TI-DS team of topical and methodology experts before being sent to external reviewers (specifically, peer reviewers and relevant TI national chapters and governments) for additional quality checks. As part of its commitment to transparency, TI-DS has published the GDI Methods Paper that outlines the methodological and analytical considerations and choices .

Overview of the Launch

The 2025 GDI research project, which will be conducted in six waves representing the TI regions, began on Tuesday 26 March 2023. A webinar was organised for TI national chapters whose countries are in the first wave. This information session ensured mutual learning between TI-DS and the chapters. Other webinars will be organised later for chapters whose countries are in the subsequent waves.

TI-DS has secured ample funding for the sub-Saharan African wave of the 2025 GDI. However, as the GDI is of utmost importance and requires timely execution, we are working towards securing additional funding to cover the administrative and operational costs of the remaining five waves. TI-DS invites the stakeholders to get in touch via gdi@transparency.org to help support the remaining waves. Thank you.

March 28, 2024 – Transparency International – Defence & Security (TI-DS) is excited to announce the start of work on the next iteration of the Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), the leading global benchmark of corruption risks in the defence and security sector.

The GDI 2025 is TI-DS’s flagship research product and follows on from the GDI 2020. This latest iteration includes expert assessments of around 90 countries as well as the introduction of a gender perspective, recognising the nuanced impacts of corruption across different gender and underrepresented groups.

The GDI provides a framework of good practice that promotes accountable, transparent, and responsible governance in the defence & security sector. It is a useful tool for civil society to collaborate with Ministries of Defence, the armed forces, and with oversight institutions, to build their capacity in advocating for transparency and integrity.

Countries are evaluated by independent assessors who assess the strength of anti-corruption safeguards and institutional resilience to corruption in five key areas:

- Financial: includes strength of safeguards around military asset disposals, whether a country allows military-owned businesses, and whether the full extent of military spending is publicly disclosed.

- Operational: includes corruption risk in a country’s military deployments overseas and the use of private security companies.

- Personnel: includes how resilient defence sector payroll, promotions and appointments are to corruption, and the strength of safeguards against corruption to avoid conscription or recruitment.

- Political: includes transparency over defence & security policy, openness in defence budgets, and strength of anti-corruption checks surrounding arms exports.

- Procurement: includes corruption risk around tenders and how contracts are awarded, the use of agents/brokers as middlemen in procurement, and assessment of how vulnerable a country is to corruption in offset contracts.

These independent assessments go through multiple layers of expert review before each country is assigned an overall score and rank. This makes the GDI extremely rigorous in its methodology.

The amount of work required to produce the GDI means the new country results will be released in six waves:

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Middle East and North Africa

- Central and Eastern Europe

- Latin America

- Asia Pacific and South Asia

- Western Europe and North America

The first wave is provisionally due to be published in early 2025.

Notes:

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI), with results published in 2013 and 2015. The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. The 2025 results can be compared with those from 2020 to get a picture of global trends in defence governance, and which countries are improving.

The GDI is a corruption risk assessment of the defence and security sector within a country, which assesses the quality of mechanisms used to manage corruption risk –and evaluating the factors that are understood to facilitate corruption.

It is not a measurement of corruption and does not measure the amount of funds that are lost to corruption, identify corrupt actors, or estimate the perceptions of corruption in the defence & security sectors by the public.

TI-DS has secured funding for the sub-Saharan African wave and is working towards securing additional support to cover the costs of producing the remaining five waves. We invite all stakeholders, including public agencies, multilateral organisations and INGOs, to get in touch via gdi@transparency.org to help support the remaining waves.

The deposed Niger government’s efforts fighting corruption contrast markedly with the neglect shown in neighbouring Burkina Faso ahead of the previous coups which rocked the region. Transparency International Defence and Security’s Mohamed Bennour, Michael Ofori-Mensah and Denitsa Zhelyazkova compare the collapse of the two nations and show how ECOWAS can reinforce democracy in the region.

Upon his election as chair of the West African regional bloc ECOWAS last month, Nigeria’s new president Bola Tinubu made plain his intentions to champion democracy in efforts to arrest the spate of military uprisings that have disrupted the region in recent years.

It wasn’t long however before another arrived, this time in Niger. ECOWAS swiftly threatened military intervention. ECOWAS and other power brokers traditionally tend to respond to events of this kind with talk of zero tolerance and sanctions – tough words but sentiment that, too often, is accompanied by minimal analysis of the root causes.

Transparency International in Niger are among the civil society groups that have observed a trend leading to coups in their country: the discovery of lucrative natural resources. In November, the Niger-Benin pipeline, the largest in Africa, is due to start exporting crude petroleum for the first time. This will multiply Niger’s crude exports by five, with an expected GDP increase of 24 per cent. Before this, the discovery of uranium in 1974 coincided with the overthrow of Niger’s leadership. Then an oil boom in 2010 was swiftly followed by another coup.

The resources vary but the outcomes follow a pattern.

The removal of Niger’s president Mohamed Bazoum has been lamented by our colleagues on the ground. This is because he had been showing willingness to step up to the long-ignored challenge of confronting corruption in the country.

Supporters of Bazoum protested in the street against the coup, together with CSOs and unions. Some have expressed their scepticism about the military being able to solve the governance challenges and issues of insecurity faced in the country.

The scepticism is driven by the fact that Niger’s security had been progressing better than in neighbouring countries, with fewer terror fatalities than those recorded in Mali and Burkina Faso.

There have been counter protests in Niger. Yet Bazoum had only been in power for two years. ANLC, (Transparency International’s chapter in Niger) had enjoyed political support from the president and parliament for the adoption of an anti-corruption law, central to addressing risks in defence and security and other sectors. This law, if and when implemented, will protect informants, witnesses, experts and whistleblowers. It will also criminalise bad practices common in Niger, such as the over-invoicing of public contracts and refusing to declare assets of civil and military figures.

Contrasting situation in Burkina Faso – decline and lost trust

The strides that had been made in Niger contrast with the decline seen in Burkina Faso, which until last week had been the nation that had suffered a coup most recently. There, a failure to secure enough resources for the army put paid to its elected leaders. Endemic corruption within the security forces contributed to the eroding of the perceived legitimacy of authorities. Public trust in government was lost. Several reports from Transparency International Defence and Security have shown how this creates dynamics for the expansion of non-state and extremist groups.

Corruption is not a victimless crime. In April, 44 civilians were killed by terrorist groups in north-eastern Burkina Faso. Later that month, a further 60 were killed by men in national military uniform in the northern village of Karma.

Ironically, Burkina Faso was considered immune to the regional spread of violence until relatively recently. Almost overnight, the land-locked state found itself a focal point in the expansion strategies of various extremist groups when a Romanian citizen was abducted in Tambao on Burkina Faso’s north-east border with Mali and Niger in 2015.

Ever since, terrorist groups, including the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), and the Burkinabe-founded Ansarul Islam have been exploiting an unresolved socio-economic crisis amid endemic corruption.

At a summit in February, the African Union announced that Burkina Faso and Mali will remain suspended from the continental bloc. Adding more pressure to the countries’ leadership, ECOWAS also extended existing sanctions on both countries, “reaffirming zero tolerance against unconstitutional change of government“.

Sanctions can be a useful tool. They deliver a clear stance against illegal and undemocratic change of power. However they do not offer lasting solutions to some of the core issues behind the takeovers. And they can risk exacerbating grievances and harming the most vulnerable groups.

In order to build a democratic and secure future in Burkina Faso, corruption in the defence sector must be tackled. There must be a focus on pragmatic reforms to ensure, and safeguard, transparency, accountability and efficacy. And civil society must be involved in the process. Our Government Defence Integrity Index provides evidence supporting arguments that the more open to civil participation and transparent a government is, the higher the level of institutional resilience to corruption.

Until last month, Niger had what Burkina has needed. National civil society was engaged with both government and the military, working for greater transparency and tackling defence sector corruption.

Now, our colleagues in Niger have called for “the immediate restoration of a civil regime supported by inclusive governance and the preservation of civic space. These measures are essential to maintain the principles of transparency and accountability that we defend.”

Not for the first time, as the international community scrambles to respond to events in the country, and watches as they continue to unfold, we have been reminded that corruption is a fundamental threat to security. Access to and control over natural resources drives power struggles that extend beyond country borders. Only driving out corruption will suffice to break the cycle for all those suffering in the Sahel.

Negotiations have been taking place in Geneva this month around the control and accountability of private military and security companies (PMSCs). Transparency International Defence and Security’s Ara Marcen Naval contributed to the discussions in Switzerland. Here she delivers a call to action to other civil society organisations.

As an NGO committed to promoting transparency and accountability in the defence and security sector, Transparency International Defence and Security (TI-DS) is deeply concerned about the corruption risks associated with the activities of PMSCs. These groups, while playing a role in enhancing security in some cases, often operate in secrecy, outside standard transparency and accountability structures. This permissive environment creates opportunities for corruption and conflict to thrive, deprives governments and citizens of financial resources, and undermines security and human rights.

I write having participated last week in the discussions of the Open-Ended Intergovernmental Working Group on PMSCs. This fourth session was convened to discuss a new draft of an international instrument to regulate the activities of PMSCs. This is a critical platform for addressing these concerns and others related to companies’ human rights obligations. There are various questions: how to ensure their activities comply with international humanitarian law? Should these companies be allowed to participate directly in hostilities?

The PMSC industry is a rapidly evolving and intrinsically international one, with a well-documented link to global conflict. The lack of regulatory oversight has led to heightened global risks of fraud, corruption, and violence, with little in the way of accountability mechanisms at both the national and international levels, so progress at a global level is key.

Current initiatives to try and regulate the market, such as the Montreux Document and the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers, are a step in the right direction. However, these initiatives have limited support among states around the world. They do not cover some key military and intelligence services and exclude some important anticorruption measures. TI-DS thinks these initiatives don’t go far enough to address the risks posed. We are hopeful that the efforts of the working group will provide a much-needed stronger set of enforceable standards.

TI-DS welcomes the progress made in the revised draft discussed last week, including references to the UN Convention Against Corruption and the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime. These references are essential steps towards policy and legal coherence, aligning efforts to regulate PMSCs with international legal obligations related to corruption and transnational organised crime.

While in Geneva I continued to propose ways that the text of the draft instrument can better incorporate anticorruption standards, including transparency of contracts and beneficial ownership, and through the recognition of corruption-related crimes as well as human rights abuses.

But we are deeply concerned about the overall lack of engagement. The room was almost empty, with many states not attending the discussions and a general lack of civil society actors actively following this critical process – prospective changes that could significantly impact conflict dynamics, international security, human rights and respect for international humanitarian law.

This is the Geneva Paradox. Other similar processes, like those related to business and human rights or others trying to get a grasp of new types of weapons systems, are filling the rooms of the United Nations, with both states and civil society in attendance. We feel that this process – which is attempting to regulate the activities of PMSCs to stop the trend of these corporate actors becoming rogue actors in wars and conflicts around the world – deserves equal attention.

In September, the Human Rights Council will set the agenda for this issue going forward. We hope that more states and civil society organisations join efforts in the coming period to give this issue the critical attention and scrutiny it deserves.