Author: harveygavin

Civil war has been raging in Sudan for soon two years with no end in sight. Its violence and destruction have caused a “humanitarian catastrophe”. Yet, as the conflict remains at the margins of media and public attention, so does one of its main drivers: corruption.

Weak defence governance and failed security sector reforms have played an important role in driving the conflict. Over the last six years, Sudan has experienced high levels of political instability, writes Emily Wegener.

Whether as a driver of the protests in 2018-2019 that forced President Omar al-Bashir out of power, or a as contributing factor to the October 2021 military coup staged by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that halted the democratic transition process, corruption continuously contributed to this volatility. Regimes fell, but the power structures and the corruption networks in and around the military and security forces survived. These networks then fuelled tensions between the SAF and RSF, which reached their breaking point in April 2023 with the outbreak of armed conflict between the two groups.

From the onset of the conflict, corruption has driven the violence. Failure to agree on a way forward in the country’s security sector reform (SSR) – the process of improving a country’s police, military and related institutions to ensure they are effective, accountable and respect human rights – is widely seen as one of the key reasons for why the democratic transition failed. Placing the RSF under civilian control and enhancing democratic scrutiny of the SAF were two of the most contentious questions in the SSR process.

But what made improving the oversight and accountability of these groups so contentious? Our 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) assessed the corruption risk as critical throughout Sudan’s defence institutions, concluding that “corruption is widespread in the sector and there are virtually no anti-corruption mechanisms”. Civilian democratic control and external oversight of defence institutions were also found to be non-existent.

An absence of accountability enabled both the SAF and the RSF to repurpose the state’s defence and security institutions to enrich high-ranking security officials and create an economy dominated by military interests. Companies owned by SAF officials have long controlled lucrative private sectors, from telecommunications to meat processing, to the detriment of public investment and sustainable economic growth. Meanwhile, the RSF controls most of the country’s gold trade – a significant income stream, considering that Sudan was the third-largest gold-producer on the continent in 2023. By the time the war broke out, the RSF owned around 50 companies, acquired largely by reinvesting the profits from gold trade into other industries. Transition to civilian rule would have meant placing the SAF under civilian oversight; for the RSF, integration into the army. When the RSF was not ready to give up its advantages, or accept this level of accountability, it declared war.

Why we produced ‘Chaos Unchained’

In February 2025, nearly two years the outbreak of the war, Sudan is facing starvation and the world’s largest displacement crisis. An estimated 30% of the population, over 11 million people, have been forced to leave their homes. According to the UN Secretary General’s latest report, over 25 million people live in food insecurity, including over 750,000 people living in conditions comparable to famine, as defined by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). Both sides, and the RSF in particular, are reported to have perpetrated ethnic cleansing and sexual violence.

Yet, the attention paid to the conflict is scarce. Sudan rarely makes the headlines. Across the international community, the focus is elsewhere. To shed light on this ‘forgotten conflict’ and its drivers, we have produced a 10-minute video looking at the origins of Sudan’s turmoil. Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan examines how corruption, kleptocratic plunder of the country’s resources and lax enforcement of arms embargoes have contributed to the ongoing conflict and the humanitarian catastrophe that comes with it.

Possible solutions

Governments and private actors can take steps to reduce the role of corruption in prolonging the fighting, and to limit the chance of relapse after a political solution is negotiated.

At international level, the UN, the EU and their Member States can:

- Recognise the links between corruption in the defence and security sector and the violence and elevate the importance of addressing corruption in the conflict resolution agenda. A strong precedent is the UN Security Council Resolution 2731/2024 on the situation in South Sudan, where the Council recognises that “intercommunal violence in South Sudan is politically and economically linked to national-level violence and corruption”, and stresses the need of effective anti-corruption structures to ensure and finance the political transition and humanitarian needs of the population.

- Explore the links between arms diversion and corruption, and the resulting circumvention of UN arms embargo and human rights abuses in the Darfur region. Existing mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Sudan and the Security Council’s Panel of Experts can contribute to improving the evidence base on the role of corruption, especially in the defence and security sectors, in fuelling the war and humanitarian crisis.

- Prioritise strengthening the rule of law and anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding. Placing the SAF and the RSF and their economic assets and activities under civilian oversight is a key step toward transparent and accountable defence and security forces. A long-term, transformative, and inclusive SSR process will be the most necessary but also the most contentious element of any negotiated solution to the conflict in Sudan. Additionally, any peacekeeping or peacebuilding interventions will need to firmly prioritise anti-corruption as a conflict prevention measure.

At national level, the governments of arms exporting countries can:

- Strengthen arms export policies and implementation guidelines. Foreign-made weapons and military equipment are being diverted into Darfur despite a long-standing UN Security Council arms embargo. Arms exporting countries can use our GDI to better assess the risk of corruption in defence institutions. Robust corruption risk assessments can help to curb diversion risks in arms sales to Sudan and the regional partners of the SAF and the RSF.

- Better regulate defence offsets. In connection with major arms sales, defence companies often negotiate lucrative offset packages with even less transparency than the arms sales. Our research has shown that defence company offsets can contribute to fuelling conflict dynamics, including in countries like Sudan by supporting industries in the UAE that help finance Sudanese armed actors. Enhancing internal and external transparency and oversight around these deals can mitigate risks of contributing to natural resource laundering for armed groups and fuelling conflict dynamics such as the one in Sudan.

Sudan shows that fighting corruption is not separate from discussions on ceasefires, political negotiations and peace processes. Integrating anti-corruption measures and fostering transparency and accountability in Sudan’s defence and security sector is key to the long-term success of any negotiated political solution.

You can watch Chaos Unchained: Conflict and Corruption in Sudan here.

Register here to join our webinar on Thursday, 6 February, in which we discuss the root causes of the conflict and pathways to peace with an expert panel.

January 15, 2025 – Transparency International – Defence & Security (TI-DS) today launches a series of policy briefs examining the institutional resilience of the defence and security sectors in Nigeria, Tunisia, Niger and Mali.

Against a backdrop of democratic backsliding, political upheaval and mounting security threats, the briefs lay out clear, country-specific policy recommendations for tackling the corruption risks undermining effective defence governance and stability across West and North Africa.

Read the briefs: Nigeria | Tunisia | Niger | Mali

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence & Security, said:

“Transparency and accountability are not only moral imperatives but also practical necessities for effective defence and security sectors. The evidence outlined in these policy briefs clearly shows the effects of weak defence governance – where corruption is allowed to fester, peace and stability suffer. Our recommendations offer governments, policymakers, and civil society organisations a clear roadmap to tackle the corrosive effects of corruption on national security.”

Each policy brief offers a blueprint for improved institutional resilience in the defence and security sector, grounded in data from our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), the world’s leading assessment of corruption risks in government defence institutions.

The analysis draws on:

- Country-specific context: Recent political events, military spending, arms imports, and public opinion on governance and democracy.

- Institutional resilience assessment: A breakdown of existing corruption safeguards and vulnerabilities in defence governance, informed by GDI data and comparisons with regional peers.

- Policy recommendations: Practical steps, developed in partnership with Nigeria/CISLAC, TI Tunisia/IWatch, and TI Niger/ANLC for improving transparency, accountability and ultimately providing peace and security for citizens.

Country summaries

Systemic corruption continues to plague the defence sector and cause a major hindrance to security in the face of significant threats. Defence budgets and procurement processes remain largely opaque. Decisive reforms to boost transparency – especially in military spending – and the reinforcing of both accountability and civilian oversight are key pillars for long-term institutional resilience.

Defence governance suffers from weak legislative functions and limited scrutiny over a highly centralised executive. With critical information restricted, parliamentary and civilian oversight remain fragile. Enhanced dialogue with civil society, clearer legal frameworks on access to information and a commitment to establishing best-practice exceptions for genuine national security concerns would go a long way to improving resilience against corruption.

A severe lack of transparency and oversight surrounds military activities, particularly defence expenditure, procurement and disposal of military-owned assets. Opening dialogue with civil society, strengthening accountability and embedding corruption risk mitigation into military operations are essential steps for rebuilding trust and stability amid the country’s evolving political landscape.

Systemic weaknesses provide opportunities for the diversion of military funds and influence-peddling, compromising both equipment on the front lines and broader political and economic stability. Defence procurement is shrouded in secrecy, blocking effective scrutiny of military purchases and how equipment is used. The release of key procurement information and auditing mechanisms are vital to creating sustainable institutional resilience against corruption.

Harnessing the power of collaboration, mutual learning, and knowledge exchange across our global Transparency International (TI) movement of over 100 chapters, Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) launched Defending Transparency: An advocate’s guide to counteracting defence corruption in August 2024. To bring this toolkit to life, we organised a series of Academy Day sessions to foster dialogue and offer hands-on training on how to effectively advocate for better anti-corruption standards in defence and security. Our International Programmes Officer, Yi Kang Choo, shares reflections on the most recent session held in Bangkok, Thailand.

On 30th November 2024, we brought together national experts from six TI Chapters across the Asia Pacific region: Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, South Korea, Pakistan, and Taiwan, for a dynamic one-day session focused on strengthening defence governance and anti-corruption advocacy through shared learning and collaboration.

The day began with an overview of the defence governance landscapes in the region. Chapter representatives shared their national experiences, highlighting challenges such as procurement practices, blurred public-private relationships in defence sectors, and limited civilian and parliamentary oversight. These discussions underscored the complexity of combating corruption and the need for innovative, context-specific solutions. Participants also candidly shared their frustrations and identified common obstacles faced by civil society in championing transparency and accountability in the defence and security sector.

One of the highlights of the day was the discussion of successful advocacy campaigns and the use of our 2020 Government Defence Integrity (GDI) Index. TI Taiwan demonstrated how the GDI alongside the chapter’s advocacy catalysed the formation of a dedicated team within the Ministry of National Defense’s (MND) Ethics Office to address the corruption risks identified in the index. TI Taiwan and the MND also co-hosted the International Military Integrity Academic Forum in 2023, fostering constructive dialogue on enhancing defence sector transparency. Similarly, TI Malaysia showcased how the GDI findings sparked public interest and facilitated further engagement with civil society in the traditionally closed and secretive defence and security sector.

These success stories inspired lively discussions, providing valuable lessons and strategies adaptable to other national contexts. We also shared findings from our latest report, Unlocking Access: Balancing National Security and Transparency in Defence. The report discusses how blanket national security exemptions are often used to justify withholding critical information, while public interest tests designed to balance the benefits of disclosing against the potential harm remain mostly absent from the cases considered. The report also features detailed case studies from five countries around the world at varying stages of progress in advancing access to information in their defence sectors, including Malaysia.

Finally, an interactive workshop followed, which encouraged participants to brainstorm and collaborate on national and regional advocacy opportunities, using the tools provided in our Advocacy Toolkit. Ideas such as fostering cross-border cooperation, engaging private sector stakeholders, and leveraging international forums like ASEAN and the Shangri-La Dialogue were central to the discussions. We also discussed how international transparency standards such as the 2013 Tshwane Principles could offer practical guidelines for governments to balance transparency and access to information with legitimate national security concerns. The session also reinforced the importance of regional and international solidarity amongst civil society in driving systemic change.

Throughout the day, the recurring theme was the importance of building and nurturing trust and partnerships. Whether engaging with defence institutions, civil society, or private companies, sustained dialogue and collaboration were seen as essential for creating lasting change. By the end of the session, participants left with actionable ideas, strengthened networks, and renewed motivation to engage on the topic moving forward. They were also invited to join our Global Defence Network, fostering further collaboration with like-minded chapters, civil society organisations, and experts worldwide.

Alvin Nicola (Democratic and Participation Governance Manager, TI Indonesia): “Fortifying alliances in the Asian region is an undeniable priority for all of us, TI Chapters. I am honoured to have the opportunity to exchange perspectives and explore collaborative steps that will further strengthen the integrity and stability of the defence and security sectors across the region.”

Dr Nausheen Wasi (Board Member, TI Pakistan): “Though, it was a brief interaction with colleagues in Bangkok, yet I thoroughly enjoyed meeting them all. I kept on thinking how the same work ideology — commitment to bring positive change in society — connects us all, regardless of diversity we inherit.”

The Academy Day reinforced our shared commitment to fighting corruption and enhancing governance of defence and security sectors in the Asia Pacific region. The lessons learned and partnerships forged will continue to guide our efforts to promote transparency and accountability in the defence and security sector. We look forward to deepening our collaboration and shared learning with Chapters across the TI movement to advance our vision of a world free from corruption in defence and security.

Defending Transparency: An advocate’s guide to counteracting defence corruption is available to read here.

Further insights from Armenia, Guatemala, Malaysia, Niger, and Tunisia illustrate access to information challenges

December 10, 2024 – New research from Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) underscores the need for better access to information in the defence sector to curb corruption, ensure accountability, and improve civic engagement.

Published today, Unlocking Access: Balancing National Security and Transparency in Defence shines a light on opaque defence sectors worldwide at a time of increased geopolitical tensions and global military spending reaching record highs of $2.4 trillion.

The report highlights challenges and good practices of transparency in defence budgets, procurement and policy processes using detailed case studies from Armenia, Guatemala, Malaysia, Niger, and Tunisia. The countries are at varying stages of progress in advancing access to information in their defence sectors and face a range of challenges, including conflict-driven secrecy, democratic backsliding, and stalled reforms.

Our analysis reveals that while international frameworks provide guidelines for transparency, implementation remains weak. Blanket national security exemptions are often used to justify withholding critical information, while public interest tests designed to balance the benefits of disclosing against the potential harm are mostly absent.

This lack of transparency increases the risk of corruption, mismanagement of funds, and fuels public distrust of the very institutions tasked with protecting citizens.

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence & Security, said:

“The defence sector remains one of the most secretive corners of government, making it a breeding ground for corruption. Striking a balance between national security and the public’s right to know is crucial to ensure accountability, but far too often governments tip the scales towards secrecy. It’s time for transparency to be the rule, not the exception.”

Case study insights

Armenia has kept high levels of defence spending because of its decades-long conflict with Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh territory, which recently concluded with major losses for Armenia. Access to information was enshrined in a 2003 national freedom of information law but has been severely curtailed by the 2024 states secrets law, which prohibits the release of information related to most defence spending.

Guatemala has endured a growing corruption crisis for the past decade, as the presidency and the powerful Public Prosecutor’s office stifled anti-corruption efforts, forced anti-corruption officials into exile, and blocked potential reform candidates from elections. As the Secretariat for Access to Public Information is required to work with the Prosecutor’s Office on access to information enforcement, implementation of the law has faltered until now.

Malaysia saw a peaceful power transition in 2018, but governance reforms – including access to information – have stalled, with the Official Secrets Act 1972 (OSA) severely limiting access to information. The OSA functions as the de facto national framework for access to information and overrules any other legislation on information access. There is little knowledge about the defence budget or expenditures, and almost no publicly available information about acquisition planning.

Niger experienced a military coup in July 2023 that has led to increased violence, stark reductions in foreign assistance, and a severe curtailing of access to information and other democratic rights. Even prior to the coup, defence income and military spending were mainly non-transparent, as were defence purchases. But a new far-reaching law was passed in 2024 that excludes all defence matters from public procurement, public accounting, and taxes.

Tunisia has seen democratic backsliding since 2021 which reduced government transparency. Though a strong access to information law exists, defence-related information is often kept confidential. Still, Tunisia has a strong access to information law, with an effective independent oversight body that has helped to implement the law throughout the public sector.

The report offers specific recommendations for each of these five countries to improve access information which broadly fit into these categories:

- Balancing tests: Legal frameworks should require officials to assess the public interest versus potential harm before withholding information.

- Proactive disclosure: Governments should regularly and proactively publish defence budgets, procurement plans, and financial results to enhance accountability.

- Independent oversight: Review bodies should be established to monitor and adjudicate disputes over information access.

- Civil society engagement: Defence planning and policymaking should be open to civil society for broader input and oversight

Notes to editors:

The case studies in Unlocking Access were produced using an updated version of our Government Defence Integrity Index 2020 – the leading global assessment of the governance of and corruption risks in defence sectors. The data was supplemented by interviews with local experts, and the review of policy reports and media investigations.

French and Spanish versions of this press release are available.

|

|

|

Corruption undermines the legitimacy and effectiveness of government institutions in all sectors, but it thrives in areas where large budgets intersect with high levels of secrecy and limited accountability, write Michael Ofori-Mensah, Denitsa Zhelyazkova and Harvey Gavin.

The defence and security sector features all these risk areas, making it particularly vulnerable. The combination of secrecy, limited oversight and, often, high levels of discretionary power in decision-making, creates an environment ripe for corruption. This vulnerability not only undermines the ability of governments to fulfil their primary duty to their citizens of keeping them safe, it also undermines their legitimacy.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is working to address this issue. A key contribution is our recent involvement in NATO’s Building Integrity Institutional Enhancement Course. This program focuses on supporting national governments with capacity building in developing Integrity Action Plans aimed at strengthening the integrity of their defence institutions. Before drawing up these plans, defence officials must identify areas most at risk of corruption. This is where the recent enhancement aimed at improving accessibility and use of our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) becomes an invaluable diagnostic tool.

The GDI is the world’s leading assessment of corruption risks in national defence institutions. As a corruption risk assessment tool, it examines the quality of institutional controls to manage the risk of corruption in nearly 90 countries around the world on both policymaking and public sector governance and covers five major risk areas:

- Financial: includes strength of safeguards around military asset disposals, whether a country allows military-owned businesses, and whether the full extent of military spending is publicly disclosed.

- Operational: includes corruption risk in a country’s military deployments overseas and the use of private security companies.

- Personnel: includes how resilient defence sector payroll, promotions and appointments are to corruption, and the strength of safeguards against corruption to avoid conscription or recruitment.

- Political: includes transparency over defence & security policy, openness in defence budgets, and strength of anti-corruption checks surrounding arms exports.

- Procurement: includes corruption risk around tenders and how contracts are awarded, the use of agents/brokers as middlemen in procurement, and assessment of how vulnerable a country is to corruption in offset contracts.

Within these areas, the GDI identifies 29 specific corruption risks, assessed through 77 main questions and 212 underlying indicators. These indicators examine both legal frameworks and their implementation, as well as the allocation of resources and outcomes.

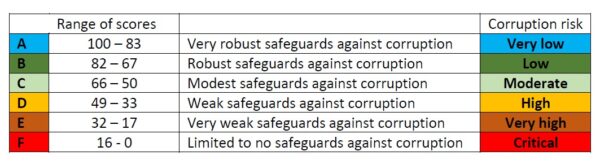

It, therefore, provides defence institutions with a comprehensive assessment of corruption vulnerabilities and a platform to identify safeguards against corruption risks. Each indicator is scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with aggregated scores determining the strength of a country’s institutional practices and protocols to manage corruption risks in defence,: from A (low corruption risk/very robust institutional resilience to corruption) to F (high corruption risk/limited to no institutional resilience to corruption).

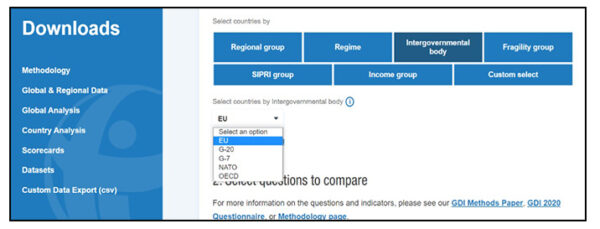

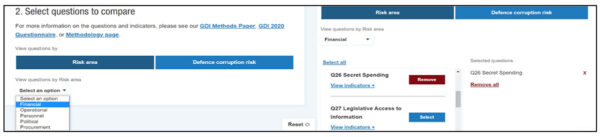

Our recent updates to the GDI website have significantly improved its functionality, allowing users to group countries by various categories such as region, income level, regime type, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) group and intergovernmental body affiliation. For example, policymakers seeking to understand problematic areas within the EU defence sector can now explore specific indicators of interest and export the data for detailed analysis.

The enhancement also provides a functionality that enables comparisons across the 77 main questions of the GDI thus facilitating targeted assessments of particular risk areas and cross-country analysis.

Data from the GDI, both quantitative and qualitative, can be downloaded in .csv format, compatible with numerous data processing tools like Excel, SPSS, and Access. This feature allows users to generate customised spreadsheets containing only the information pertinent to their needs. The qualitative data, derived from expert assessor interviews, provides critical insights that complement the quantitative scores, offering a nuanced understanding of corruption risks.

(Note: these updates apply to the current 2020 iteration of the GDI. Our team is working on the 2025 GDI – you can find more information about it here)

The ongoing challenges posed by corruption in the defence sector demand sustained and coordinated efforts from both national governments and the international community. Initiatives like NATO’s Building Integrity Institutional Enhancement Course, supported by tools like the GDI, represent significant strides toward fostering good governance in defence institutions. But maintaining high standards of defence governance remains an ongoing challenge that requires vigilance and commitment.

Reforms are urgently needed to address the institutional gaps identified by the GDI. Integrity Action Plans, informed by comprehensive corruption risk assessments, are essential for guiding these changes. By prioritising transparency, accountability and resilience, countries can strengthen their defence institutions, reduce corruption and improve peace and security.

The Geneva Peace Week (GPW) is one of the important appointments on the international peacebuilding calendar, writes Francesca Grandi, our Senior Advocacy Expert. This year, it centred around the question: “What is Peace?”

A call to action and an opportunity for reflection, the forum brought together a wide array of stakeholders from the peace and security ecosystem and beyond, highlighting the cross-cutting nature of peacebuilding and the need for innovative and collaborative solutions for building lasting peace.

Building bridges

Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) attended GPW 2024 to make the case for recognising corruption in the defence and security sectors as a key driver of violence and armed conflict, and to advocate for a more comprehensive and systematic inclusion anti-corruption measures in peacebuilding frameworks. We introduced our research and engaged with many panels. Colleagues in international NGOs, UN bodies, and Member States expressed a genuine interest in our work and acknowledged the importance of addressing corruption in the defence and security sector to build trust and resilience in fragile contexts. It was clear that more research and practical tools are needed to bridge what we know about corruption and armed conflict.

Anti-corruption as a preventive tool

In nearly every session, the themes of prevention, trust-building, and institutional resilience resonated strongly with our message that anti-corruption contributes to postive peace and security outcomes and provides a relevant lens across a wide range of peace and security issues.

Corruption hampers the effectiveness of security sector reforms, arms controls, and truth and reconciliation processes; it undermines the protection and promotion of human rights; it erodes trust between former combatants and government institutions, and thus the successful reintegration of ex-combatants, increasing the likelihood of conflict relapse.

We asked whether corruption is sufficiently integrated into international peace frameworks, such as the UN Pact for the Future. While some peacekeeping mandates include anti-corruption provisions, the absence of explicit references in key documents remains a concerning omission.

By addressing corruption as a root cause of conflict and ensuring that public resources are used as intended, we can build more resilient and inclusive societies and enhance the impact of localised and gender-responsive peacebuilding approaches. By integrating anti-corruption strategies in our peace responses, we can strengthen institutional integrity and help foster the public trust and the institutional resilience needed for lasting peace.

Next steps: Expanding partnerships and advocating

Moving forward, TI-DS remains committed to advocating for integrating anti-corruption as a key component of the global peace and security agenda and for including corruption prevention strategies in future peace interventions, emphasising their role in strengthening governance and peace processes.

As we continue our advocacy efforts, our focus remains on building partnerships, producing evidence-based research, and ensuring that anti-corruption remains at the forefront of global peace and security discussions. The GPW provided us with a platform to advance these objectives, and we look forward to furthering our work in this vital space.

Two years have passed since Burkina Faso witnessed its second coup within a year, on September 30, 2022, plunging the troubled nation into deeper instability and uncertainty.

Since these pivotal events, it is important to examine some of the governance factors that led to them and the profound impact they have had on the country’s security and its people. The coups in Burkina Faso are not isolated incidents but symptoms of long-standing issues in the nation’s defense and security sectors, made worse by persistent corruption and weak governance, write Michael Ofori-Mensah and Harvey Gavin.

The first coup in January 2022, led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, was partly fuelled by the Burkinabè government’s inability to contain the growing jihadist insurgency that has plagued the region as well as weak civilian oversight of the military. Despite international support and initiatives aimed at stabilising the country, the government’s efforts faltered, leaving the population increasingly vulnerable to extremist violence. This continued failure eroded public trust in the government’s leadership. After a series of anti-government protests, the country’s democratically elected president, Roch Kaboré, was ousted by members of the Burkina Faso Armed Forces on January 23.

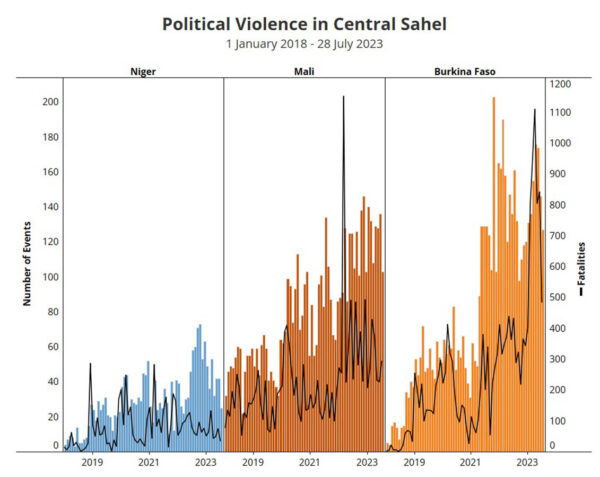

Just months later, on September 30, 2022, a second coup, led by Captain Ibrahim Traoré and comprised of other members of the armed forces frustrated with the lack of progress in improving the security situation, overthrew the leaders of the first. But instead of paving the way for stability, this second coup further destabilised the country, deepening the security crisis and undermining any prospects for effective governance. Figures from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project show 1,985 civilians were killed in Burkina Faso during the two years leading up to the second coup (from September 30, 2020, to September 30, 2022). Despite the leaders of both coups claiming they would improve the security situation, 4,843 civilians were killed in the two years after September 30, 2022.

At the heart of Burkina Faso’s instability lies a deep-seated problem of weak governance and pervasive corruption within the defence and security sectors. Our 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) found that the country faces considerable corruption risk across its defence institutions, with little to no transparency or controls across finances and procurement. These issues significantly contributed to weakening the resilience of the military and its ability to effectively address the jihadist threat.

Corruption within the country’s defence and security sector has diverted resources away from critical security needs, weakening the military’s operational capabilities while eroding the trust between the armed forces and the civilian government. This was highlighted in 2021 when in June jihadists killed more than 100 people in Solhan, a village in the north of the country. In November of the same year a further 49 police officers and four civilians were killed near Inata, in the same region. A memo from security forces in the area warned their superiors that they had run out of food and had been forced to commandeer livestock from citizens. The lack of safeguards against corruption in defence and security institutions has played a major role in the deteriorating security situation, creating fertile ground for insurgent groups to exploit and thrive.

The ongoing jihadist insurgency has had devastating effects on Burkina Faso’s security landscape and its people. Attacks have become more frequent and brutal, targeting both military personnel and civilians, with more than 6,000 people killed – including around 1,000 civilians – between January and August this year. The pervasive insecurity has created a climate of fear and instability, with entire communities displaced.

The inability of successive governments to effectively address the insurgency has only exacerbated the situation. Each failed attempt to quell the violence has diminished public confidence in the government and increased public frustration. This frustration has, in turn, provided fertile ground for military coups, which, rather than resolving the underlying issues, have led to further instability.

New research from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies highlights vividly the scale of this instability. The Sahel region accounts for more than half of all annual reported fatalities (11,200) involving militant Islamist groups in Africa. Burkina Faso bears the majority of this violence (48 percent) and fatalities (62 percent) linked to militant Islamist groups in the Sahelian theater.

Note: Compiled by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, each map shows violent events involving the listed groups for a year ending June 30. Group designations are intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered official. Due to the fluid nature of many groups, affiliations may change.

Sources: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); Centro Para Democracia e Direitos Humanos; Hiraal Institute; HumAngle; International Crisis Group; Institute for Security Studies; MENASTREAM; the Washington Institute; and the United Nations.

Beyond the political and security implications, the escalating jihadist insurgency has had a profound impact on human security in Burkina Faso. The civilian population bears the brunt of the violence, facing daily threats to their lives and livelihoods. Families have been torn apart, and communities have been shattered by the constant threat of violence and displacement.

Had there been greater resilience and integrity within Burkina Faso’s defence and security institutions, the trajectory of the country’s security situation might have been different. Strong, accountable institutions are essential for maintaining internal stability and effectively countering security threats. They build public trust, ensure the proper allocation of resources and foster cooperation between military leadership and the population they are entrusted to protect.

Two years since the September 2022 coup, it is imperative for regional bodies like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the international community to renew their commitment to supporting Burkina Faso. While international forces are no longer in the country,

The past two years have underscored the urgent need for comprehensive reforms in Burkina Faso’s defence and security sectors. The recurring coups, driven by the government’s inability to manage the jihadist insurgency, have only deepened the nation’s challenges, leading to greater instability and suffering for its people.

Burkina Faso stands at a crossroads, grappling with the fallout of a series of coups which have been fuelled by a lack of integrity, accountability and transparency in its defence and security sector. The withdrawal of international forces, including UN personnel, has left civilians vulnerable to escalating jihadist violence, as evidenced by recent reports documenting significant civilian casualties. Meanwhile, the Burkinabè armed forces have also suffered heavy losses.

The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States, following Burkina Faso’s exit from ECOWAS, complicates the prospects for meaningful dialogue and reform. Amidst the global focus on conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza and Lebanon, the profound human tragedy unfolding in Burkina Faso and the wider Sahel region must not be overlooked. It is imperative for ECOWAS and the African Union to take decisive action, with the support of the international community, to strengthen defence governance as part of broader reforms. Cooperation, not competition, is key to addressing the corruption and insecurity issues the region faces. Civil society should have guaranteed freedom of expression, and space, to participate in the peacebuilding and conflict prevention process. The Burkinabè government needs to provide mechanisms for this participation, as well as broaden public debate on defence issues and policies.

Overall, commitment to civilian democratic oversight of the armed forces is essential for building a resilient defence sector and ensuring the protection of the Burkinabè people.

As members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) gather this week in Laos for the 44th and 45th ASEAN Summits, this blog by Yi Kang Choo, our International Programmes Officer, explores the concerning absence of a strong focus on corruption risks – particularly in the region’s defence and security sectors.

Given the steady rise in military spending in the region, the ongoing civil war in Myanmar, and heightened tensions over territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea involving ASEAN nations, a discussion about how to root out corruption, and increase resilience to it, in these sectors seems overdue.

Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS), alongside national TI Chapters in Indonesia (TI-ID) and Malaysia (TI-M) urge ASEAN states to recognise the pressing threat that corruption in the defence sector poses to regional peace and security. As Malaysia prepares to take on the role of ASEAN Chair in 2025, Transparency International Malaysia specifically highlights the crucial need for Malaysia especially to champion collective anti-corruption initiatives, particularly within defence and security sectors across the region. Malaysia needs to use its leadership by demonstrating that it is executing its national anti-corruption strategies with greater transparency and how such initiatives will help the ASEAN region as a whole.

Recent data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) highlights that global military expenditure reached a record high of $2.443 trillion in 2023, with ASEAN member states seeing an average rise of 2.34% since 2022. As our research shows, increased defence spending without appropriate oversight often correlates with rising corruption risks. In systems already susceptible to corruption, an influx of funds is most likely to benefit corrupt actors, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that prioritises private gains over peace and security outcomes.

Our Government Defence Integrity (GDI) Index shows nearly half of all ASEAN member states face high to critical corruption risks in their defence sectors. This includes Malaysia, the incoming ASEAN Chair in 2025. Corruption can severely undermine the reliability and quality of military infrastructure and equipment, divert critical public resources, and compromise the safety and operational effectiveness of armed forces during potentially critical situations.

Additionally, effective civilian oversight of defence institutions remains limited across the region, especially given the restrictive civic spaces in all ten ASEAN countries, which have been categorised as ‘closed’, ‘repressed’, or ‘obstructed’ according to 2023 CIVICUS Monitor rating.

To address these urgent challenges, TI-DS calls on ASEAN member states to:

- Recognise and respond to corruption as a threat to peace and security – Corruption exacerbates inequalities within and between nations, fuelling conflicts and geopolitical tensions. ASEAN must prioritise strengthening governance systems, embedding corruption safeguards, and building integrity within its armed forces into defence and security decision-making.

- Create mechanisms for meaningful civil society engagement and effective parliamentary and civilian oversight in defence and security sectors – To ensure these sectors operate under effective scrutiny and accountability, civil society must be empowered to fulfil its role as critical observer in an independent, protected and effective manner. This includes the protection of civic space and ensuring public access to information, also in defence and security, with restrictions on the grounds of national security only applied on well-justified, exceptional circumstances. Additionally, whistleblowers and investigative journalists must be protected from retaliation, particularly when transparency serves the public interest over secrecy.

- Implement robust anti-corruption controls for arms transfers – Governments must conduct thorough corruption risk assessments for arms deals and ensure recipient countries uphold strong anti-corruption standards. Measures must be taken to prevent arms from being diverted and misused. (Read our briefing paper to learn more about how arms trade loopholes enabled crimes against humanity in Myanmar.)

Against the backdrop of heightened security risks, we call for ASEAN governments to prevent further risk for conflict and tensions through taking anti-corruption and its risks to defence, peace and security seriously, as well as to fully acknowledge the role of civil society in embarking on this vital endeavour for the region.

Notes to editors:

ASEAN Member States including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Myanmar feature in Transparency International Defence & Security’s 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI).

The Index scores and ranks countries based on the strength of their safeguards against defence and security corruption.

Malaysia and Indonesia appear in band ‘D’, indicating a ‘high’ risk of corruption, whereas Thailand appear in band ‘E’, indicating a ‘very high’ risk of corruption, and Myanmar in band ‘F’, indicating a ‘critical’ risk.

Access to information is a cornerstone of healthy, accountable and transparent societies and essential for democracy.

By improving the public’s ability to obtain and use government-held information, citizens are empowered to participate fully in democratic processes, make informed decisions, and hold their leaders accountable.

Access to information is vital in all public sectors, but particularly so in defence and security where high levels of secrecy combined with substantial public budgets greatly increase the risk of corruption. Transparency and access to information in this sector provides a crucial bulwark against the misuse of funds, ensures accountability, and maintains public trust.

Ahead of Access to Information Day 2024, we’re excited to share details of our upcoming report which provides a comprehensive overview of the state of defence transparency and access to information worldwide.

Our report aims to strengthen accountability by enhancing access to defence information, in line with our broader goal to ensure informed and active citizens drive integrity in defence and security.

Utilising our Government Defence Integrity (GDI) 2020 database, which assesses institutional integrity and corruption risks, the report offers a detailed assessment of global defence transparency and access to information, with a focus on defence finances including budgeting information and spending practices. This is particularly urgent in an era of increasing military spending. The latest defence spending data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) shows world military expenditure rose for the ninth consecutive year to an all-time high of $2.443 trillion in 2023. This represents an increase of 6.8 per cent in real terms from 2022, which is the steepest year-on-year increase since 2009.

Additionally, the report also includes a review of global standards for transparency that apply to the defence sector. This is coupled with insightful case studies from Niger, Tunisia, Malaysia, Armenia and Guatemala and a review of good practices. The report concludes with recommendations to enhance access to information in particular contexts.

We look forward to sharing the full report and the accompanying case studies shortly. Updates on the launch date will be provided via our X/Twitter and LinkedIn accounts.

Join us in New York for our Summit of the Future Action Days side event.

Date: Thursday, September 19

Time: 09:00 EDT

Location: Millennium Hilton New York, One UN Plaza, New York

About

Corruption is a driver, root cause and consequence of armed conflict, violence and insecurity. Cross-cutting by nature, it impedes investment in and implementation of the entire 2030 Agenda. Strengthening resilience to corruption by improving governance of the public sector can supercharge progress on sustainable peace and development by building trust in public institutions, safeguarding resources, preventing violence and increasing our resilience to threats and shocks.

In recent years, preventing and combatting corruption has moved down the global agenda. Corruption is often seen as a bureaucratic, victimless crime, the fight against which is desirable, but not a priority. This could not be further from the lived experience of those affected by it. Where corruption is linked with violence and insecurity, it becomes something much bigger: a human rights issue, a development issue, and an equality issue.

Multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow must focus on addressing the risk corruption poses to international peace and security. The Summit of the Future is an opportunity to bring good governance back into the spotlight.

Join us on Thursday 19 September, 09:00 EDT to explore the existing gaps in addressing corruption and how we can work together to resolve them. We will discuss how the Pact of the Future can be a vessel for progress to combat corruption as a serious threat to peace and security, human rights, and sustainable development.

Speakers

Opening remarks:

Tara Soomro, UK ECOSOC Ambassador, UK Mission to the UN

Delphine Schantz, Representative, UNODC New York Office, UNODC

Panel:

Jikang Kim, Policy team leader/HRDDP Advisor, Peace Missions Support Section, UN OHCHR

Oana-Raluca Topala, Coordination Officer, Security Sector Reform Unit, UN DPO

Jonathan Bourguignon, Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Officer (Anti-corruption), UNODC

Ara Marcen Naval, Senior Strategy Advisor, Transparency International Defence & Security

Graeme Simpson, Director of Interpeace USA Office, Interpeace

How to attend

A year on from the coup d’etat in Niger, Denitsa Zhelyazkova looks back at what has changed so far and what needs to happen to address corruption in the country’s defence sector.

Last month marked an important date for political leaders and human rights advocates all around the globe: one full year after the coup d’etat in Niger. On July 26, 2023, senior army officers from the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (Conseil National pour la Sauvegarde de la Patrie, or CNSP), led by General Abdourahamane Tchiani, seized power, suspended the constitution and detained country’s democratically elected leader, President Mohamed Bazoum. The junta claimed the reasons for the coup were the continuous deterioration of the security situation under Bazoum and poor economic management, among others. On August 20 that year, the coup leader proposed a three-year transition plan back to democratic rule, but concrete steps towards this have yet to materialise. Even though the 2023 mutiny was not a new phenomenon for the region, especially given the number of recent putsches in neighbouring Mali and Burkina Faso, this coup signifies a pivotal point in Nigerien politics.

Major changes since the coup

- Cutting ties with the West and regional actors: Niger is heading for a shift in strategic alliance and moving away from traditional Western security providers. Strengthening regional ties with Mali and Burkina Faso under a new mutual defence pact called the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) resulted in the new ‘Confederation of Sahel States’, emphasising both economic and military cooperation. They signed a treaty on the July 6 this year restating their sovereignty from France’s influence in the region, their departure from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), as well as their aim to create a new common currency. In addition to potentially having catastrophic economic and further humanitarian consequences, this step will likely complicate relations with neighbouring states and reshape international influence in the Sahel region.

- New anti-corruption body: General Tchiani has dissolved two of the country’s highest courts, the Court of Cassation and State Council, replacing them with a new anti-corruption Commission and a State Court. The commission’s main role will be recovering all illegally acquired and misappropriated public assets. Consisting of judges, army and police officers as well as representatives of civil society, the selection process of these members lacked transparency. Furthermore, it is not clear at this stage whether the anti-corruption regulations discussed under Bazoum will be implemented and whether the transitional commission and court can have an impact on that.

Damage

Turning away from democracy rarely leads to peace and stability.

In the immediate aftermath of the coup, violence and human rights abuses spiked, with Human Rights Watch reporting that CNSP supporters looted and set fire to the headquarters of Bazoum’s party, the Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS).

France, the EU, and the US condemned the coup and suspended development aid. UN humanitarian operations were also stopped. The African Union (AU) responded by suspending Niger, while ECOWAS closed its borders, demanded Bazoum’s release, and threatened military intervention and sanctions. Tensions escalated further as Mali and Burkina Faso warned that ECOWAS intervention would be considered a ‘declaration of war’ against them.

The putsch and its direct economic consequences are now threatening to worsen human suffering in the landlocked country that has been grappling with poverty, political instability and endemic corruption for decades. Being one of the poorest countries in world, Niger recently ranked 189 out of 193 territories in the critical HDI value from the UN’s Human Development Index, signalling a dire humanitarian crisis. Even though ECOWAS sanctions were lifted in February this year for humanitarian purposes, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported a surge in humanitarian need. An additional 600,000 people required humanitarian assistance in 2023, to an estimated total of some 4.3 million people, as extreme poverty is expected to reach 52%. Despite faring comparatively better against Burkina Faso and Mali in terms of fatalities, Niger is still suffering with violence and internal turmoil, with over 370,000 internally displaced people, primarily consisting of women and children.

ACLED graph using their own data on political violence, August 3, 2023.

The vicious cycle of conflict and corruption

Niger has been struggling with jihadist violence and security threats on several fronts, from IS Sahel and the al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM in the west and south of the country, to bandits, organised crime networks in resource-rich Agadez as well as Tahoua, and even Boko Haram rebels around Diffa near the border with Nigeria. Despite these serious security challenges, historically weak governance of the defence sector has been eroding Niger’s capabilities to defend its own citizens. An embezzlement case in 2020 revealed how a notorious arms dealer exploited government contracts for nearly a decade to funnel hundreds of millions of dollars to purchase weapons from Russia. With more than $130 million lost to corruption in this case alone, it brought to light just how urgent reform of the security sector, with anti-corruption at the core, is.

Now that the country is ruled by a military government, increased levels of secrecy are expected to rise around defence planning and spending, as well as personnel recruitment and payments. The newly adopted Ordinance 2024-05 of February 23, 2024, is a huge step backwards in terms of good governance in the security sector, allowing for even more opaque practices in defence budget planning and management. The new decree dictates that public procurement and public accounting expenses related to the acquisition of equipment, materials, supplies, as well as the performance of works or services intended for the Defense and Security Forces (FDS) are exempt from regular oversight regulations. Moreover, defence expenses are exempt from taxes, duties and fees during the transition period. Unfortunately, opaque practices have become the norm when it comes to Niger’s defence governance.

The 2020 iteration of Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) found that Niger faces a very high level of corruption risk, which is consistent with other fragile and conflict-affected states in the region. The results showcase the country’s issue with building robust institutions despite increased military spending and advanced operational training by Western allies in the past years. Scoring in the bottom quarter of the GDI 2020, Niger received the lowest score of all West African countries assessed in the index, with secrecy and opaque procurement practices being the biggest concerns. According to the 2013 Decree on defence and security procurement, Niger’s defence acquisition plan is not subject to public disclosure and is classified as “top secret,” nor is the plan subject to legislative scrutiny by the Security and Defence Committee. Despite the egregious 2020 embezzlement case, findings from a 2022 audit on state spending estimate budget discrepancies of approximately $99 million. Greater public oversight of defence spending, not expanded exemptions from transparency for the military and security services, is vital to restoring public trust and to ensure much-needed funds are not lost to corruption. Considering the new cooperation agreements with global actors notorious for the high levels of corruption risk in their defence sectors – such as Russia and Turkey – it is crucial for Niger to prioritise transparency and accountability in its defence governance.

One key rationale the military provided for the taking power last year was the worsening security in the country. However, violence has persisted and escalated, calling into question the effectiveness of military operations. Oversight of military spending has also been curtailed. Corruption in the defence sector not only hinders military capabilities, but also erodes public trust in the very institutions established to protect citizens. If opaque practices persist, allowing greedy officials to benefit while citizens continue to suffer, this can bring even more instability. Following the steps of Mail and Burkina Faso could potentially drag Niger into a vicious cycle of coups, violence, loss of territory to rebels, and of course the fuel driving the cycle – widespread corruption in the security sector. The path to democracy inevitably starts with focusing efforts on building resilient institutions and addressing corruption as a top priority through an urgent (and long-overdue) security sector reform.