Author: harveygavin

By Julien Joly, Thematic Manager, Corruption, Conflict and Crisis, Transparency International Defence & Security

Corruption, conflict and instability are profoundly intertwined. It has been shown time and again that corruption not only follows conflict but is also frequently one of its root causes.

Broadly speaking, corruption fuels conflict in two ways:

- By diminishing the effectiveness of national institutions; and

- By generating popular grievances.

Both of these elements contribute to undermining the legitimacy of the state, and in conflict this can empower armed groups who present themselves as the only viable alternative to corrupt governments. In turn this further contributes to the erosion of the rule of law, thus fuelling a vicious cycle.

Despite this, relatively little attention has been given to addressing corruption through peacebuilding efforts. As corruption is increasingly recognised for its role in fuelling conflict and insecurity around the world, it is imperative that initiatives seeking to address the root causes of violence and build lasting peace take this into consideration.

As a key element of the post-conflict peacebuilding agenda, Security Sector Reform (SSR) lends itself ideally to address the nexus between corruption and conflict. Applying the principles of good governance to the security sector to ensure that security forces are accountable offers legitimate avenues to mitigate corruption.

Nonetheless, evidence shows that strategies to mitigate corruption often fail to receive sufficient attention when it comes to designing and implementing SSR programmes. Such programmes overwhelmingly target tactical and operational reforms, designed for instance to train security forces or provide them with weapons and equipment, at the expense of structural reforms which would focus on bolstering accountability and reducing corruption. Similarly, in SSR policy frameworks developed by international and regional organisations, corruption is too often mentioned superficially and largely marginalised in favour of the ‘train-and-equip’ approaches described above. However, since the emergence of the concept of Security Sector Reform (SSR) in the 90s, there has been a shift from state-centric notions of security to a greater emphasis on human security. In this paradigm, based on the security of the individual, their protection and their empowerment, traditional ‘train-and-equip’ approaches to SSR have shown their limits.

It is clear that transparency, accountability, and anti-corruption are vital to ensure that security sector governance is effective. This means developing new approaches to SSR that, among other things, address corruption effectively.

In many areas, the anti-corruption community and the peacebuilding community would benefit from each other’s expertise. Reforming human resources management and financial systems, strengthening audit and control mechanisms, supporting civilian democratic oversight: these are areas where anti-corruption practitioners have been developing significant expertise over the past decades. They also happen to be key components of SSR.

But drawing from this expertise is only the beginning. In order to promote sustainable peace and contribute to transformative change in security sector governance, SSR needs to take a corruption-sensitive approach and address corruption as a cross-cutting issue. This requires implementing anti-corruption measures as a thread running through all SSR-related legislation, policies and programmes. In other words, this requires ‘mainstreaming anti-corruption in SSR’, which involves making anti-corruption efforts an integral dimension of the design, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of SSR policies and programmes.

While strengthening accountability and effectiveness in the security sector, anti-corruption provisions in SSR can be crucial in addressing some of the drivers and enablers of conflicts. Moreover, by upholding high standards of accountability, probity and integrity within the defence and security forces, anti-corruption fosters the protection against human rights abuses and violations. Ultimately, mainstreaming anti-corruption into SSR can harness its capacity to create political, social, economic and military systems conducive to the respect for human rights and dignity, ultimately contributing to long-lasting human security.

This blog is based on The Missing Element: addressing corruption through SSR in West Africa, a new report by Transparency International Defence and Security, available here.

February 25, 2021 – Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts in West Africa are being undermined by a failure to address underlying corruption and a lack of accountability in the region’s security sectors, according to new research by Transparency International.

The Missing Element finds that strengthening accountability and governance of groups including the armed forces, law enforcement and intelligence services – not just providing training and new equipment – is a crucial but often neglected component to successful security sector reform (SSR).

By analysing examples from across West Africa, the report details how the high threat of corruption has undermined the rule of law, fuelled instability, and ultimately resulted in SSR efforts falling short of their objectives.

The report serves as a framework for policymakers to assess how corruption is fuelling conflict, then embed anti-corruption measures to reform the security sector into one which is more effective at maintaining peace and more accountable to the population it serves.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts across West Africa have focussed largely on providing training and equipment but rarely resulted in major change. This report details how a focus on anti-corruption and strengthening accountability has been the missing element. Only by recognising and understanding the impact of corruption in the defence and security sector and taking steps to combat it can these programmes hope to transform the sector into one which is both efficient and accountable.”

The Missing Element analyses security sector reform and governance in five countries that our research has previously flagged as being at a high risk of defence sector corruption: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria.

It concludes these interventions fell short because the focus was on providing practical support such as training programmes and new weapons and equipment (with between 80-90% of funding for SSR initiatives typically spent on these) rather than addressing underlying corruption.

The report assesses the main corruption risks in West Africa which are undermining SSR efforts, including:

Financial management

Limited or ineffective supervision over how defence budgets are spent present a huge corruption risk, but reforms to improve transparency in this area have often been neglected as part of SSR programmes.

National defence strategies in Niger and Nigeria are so shrouded in secrecy that it is impossible to determine whether defence purchases are legitimate attempts to meet strategic needs or individuals embezzling public funds. In Mali, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire, a lack of formal processes for controlling spending has resulted in numerous examples of unplanned and opportunistic purchases.

Defence sector oversight

Effective oversight and scrutiny of the defence sector by parliamentarians is essential to increase accountability and reduce opportunities for corruption, but despite being a key pillar of SSR, parliamentary oversight remains poor in West Africa.

In Ghana, only a handful of the 18 members of the Parliament Select Committee on Defence and Interior have the relevant technical expertise to perform their responsibilities. In Mali, the parliamentary body charged with scrutinising the defence sector was chaired by the president’s son until mid-2020. In Niger, the National Audit Office, which is responsible for auditing the defence sector’s spending, published its audit for 2014 in 2017.

Recommendations:

- SSR policymakers at institutional level, such as United Nations (UN), African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), to publicly acknowledge the nexus between corruption and conflict, and adapt SSR policy frameworks accordingly.

- SSR practitioners operating in West Africa to undertake corruption-responsive SSR assessments to better inform the design of national SSR strategies and in all phases of their implementation.

- SSR practitioners to build on anti-corruption expertise to ensure that corruption is addressed as an underlying cause of conflict.

Notes to editors:

Security sector refers to the institutions and personnel responsible for the management, provision and oversight of security in a country. Broadly, the security sector includes defence, law enforcement, corrections, intelligence services and institutions responsible for border management, customs and civil emergencies.

Security sector reform (SSR) is a process of assessment, review and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation led by national authorities that has as its goal the enhancement of effective and accountable security for the state and its peoples without discrimination and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law.

The five countries analysed in this report (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria) were previously assessed in Transparency International Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index.

About Transparency International Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.

By Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy – Transparency International Defence & Security

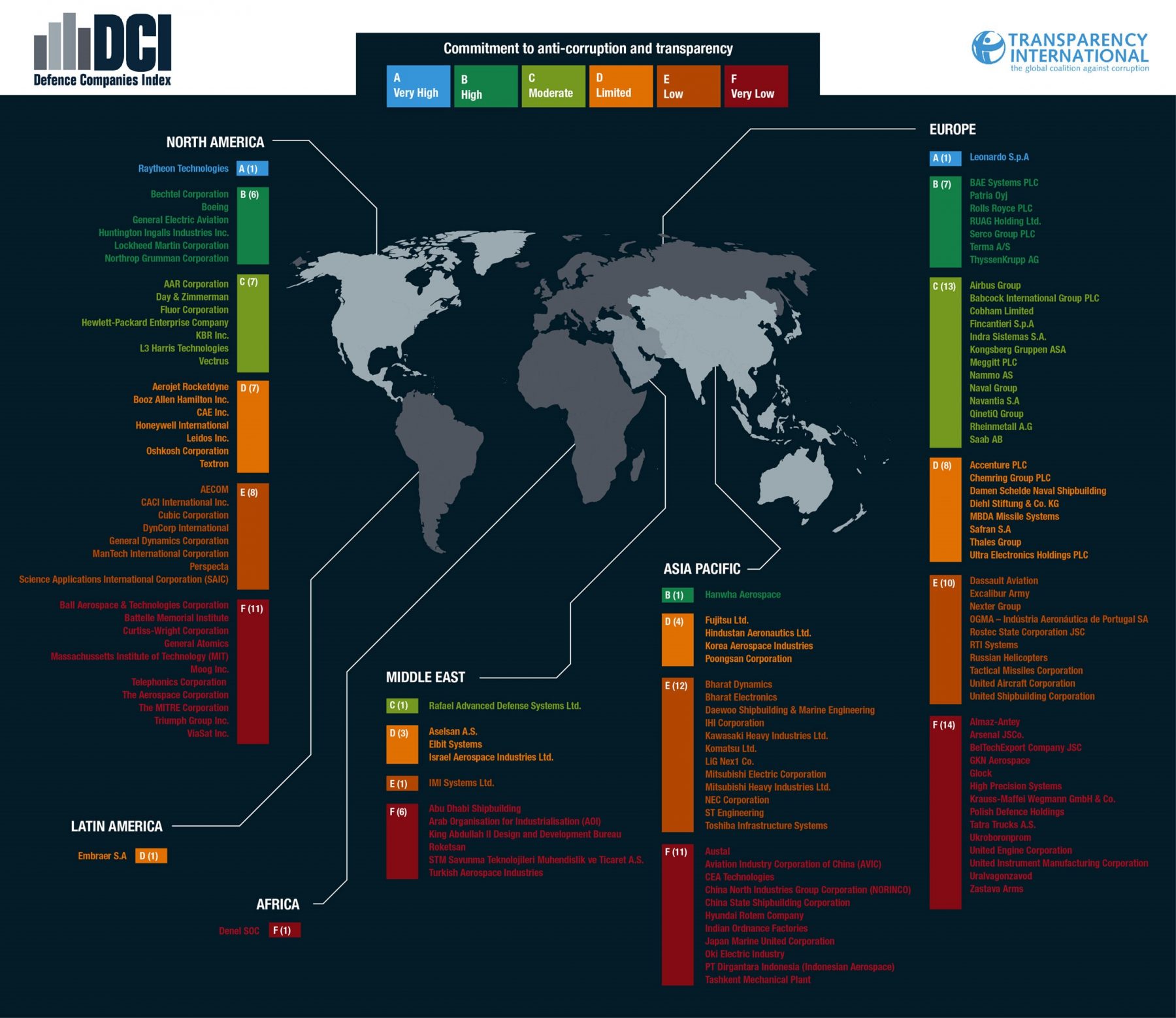

Nearly three-quarters of the world’s largest defence companies show little to no commitment to tackling corruption. That’s the headline finding from our newly published Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI). It assesses 134 of the world’s leading arms companies, ranking their policies and approach to fighting corruption from A to F.

The statistic is deeply concerning, if not altogether surprising to those familiar with the defence industry. Reducing corruption in the defence sector is imperative to guarantee safety and security. Yet, a veil of secrecy, invoked ostensibly in the interests of national security, shrouds the defence sector’s activities making it especially vulnerable. The widespread use of middlemen, whose identities and activities are kept secret, further limits oversight. The impact of corruption in the arms trade is particularly pernicious. The high value of defence contracts means that huge amounts of public money may be wasted, instead of being spent on essential public services. Corruption can encourage the excessive accumulation of arms, increase the circumvention of arms controls and facilitate the diversion of arms consignments to unauthorized recipients, perpetuating conflict and costing lives and undermining democracy.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, of the world’s 10 largest importers of major arms between 2015-2019, eight countries – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq and Qatar, UAE, China and India – are at high, very high or critical of corruption in the defence sector as measured by our Government Defence Integrity Index, the DCI’s sister index. Critical risk of defence sector corruption means major arms are sold to countries where they are likely to further fuel corruption, and where appropriate oversight and accountability of defence institutions is virtually non-existent.

The findings of the DCI add to this worrying picture. Nearly two thirds (61%) of the companies assessed show no clear evidence of policies or processes to assess and manage risk in markets they operate in. In addition, only 10% of the companies actively disclose full details of countries in which they and their subsidiaries operate, leaving a major gap in transparency and oversight of corporate activity.

Click here to view full screen.

The DCI has revealed that many companies score well on the quality of their internal anti-corruption measures, such as public commitments to fighting corruption and processes to prevent employees from engaging in bribery. However, because most companies publish no evidence on how these policies work in practice, it is impossible to know whether they are actually effective. Many firms do not publicly acknowledge they face increased risks when doing business in corruption-prone markets nor do they have apparent measures in place to identify and mitigate these risks. Few take measures to prevent corruption in ‘offsets’ – controversial side deals that involve a company reinvesting some of the proceeds of an arms deal into the customer’s economy but are banned in other sectors because of the corruption risks such deals pose – and most do little to counter the high-risk of bribery associated with using agents and intermediaries to broker deals on their behalf.

It is essential that companies have procedures in place to deal with these often opaque and high-risk aspects of the defence sector – including agents and intermediaries, joint ventures, offset contracting and operating in geographies considered at high risk of corruption.

We urge defence companies to increase corporate transparency through meaningful disclosures of:

- their corporate political engagement – a particularly high-risk issue in the defence sector -including their political contributions, charitable donations, lobbying and public sector appointments for all jurisdictions in which they are active;

- their procedures and the steps taken to prevent corruption in the highest risk areas, such as their supply chain, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures and offsets;

- procedures for the assessment and mitigation of corruption risks associated with operating in high-risk markets, a major risk for defence companies, as well as acknowledgement of the corruption risks associated with such practices;

- beneficial ownership and advocate for governments to adopt data standards on beneficial ownership transparency;

- all fully consolidated subsidiaries and non-fully consolidated holdings, and to state publicly that they will not work with businesses which operate with deliberately opaque structures; and

- the nature of work, their countries of operation and the countries of incorporation of their fully consolidated subsidiaries and non-fully consolidated holdings.

The DCI provides a roadmap for better practice within the defence industry. It promotes appropriate standards of anti-corruption and transparency of policies and procedures suited to the risks faced in the defence sector. Adopting these will not only reduce corporate risk, but also increase accountability and reduce the risk of corruption in the sector more widely.

ARMS INDUSTRY MUST DO MORE TO IMPROVE QUALITY AND TRANSPARENCY OF ANTI-CORRUPTION MEASURES

February 9, 2021 – Nearly three-quarters of the world’s largest defence companies show little to no commitment to tackling corruption, new research from Transparency International reveals.

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) is the only global index that measures the commitment to transparency and anti-corruption of the world’s leading defence companies.

Key findings:

- Just 12% (16) of the 134 companies assessed receive a top ‘A’ or ‘B’ ranking, demonstrating a high level of commitment to anti-corruption.

- 73% (98) received a ‘D’ or lower, indicating little commitment to transparency and anti-corruption.

- Of the 36 companies that scored a ‘C’ or higher, 21 are based in Europe and 13 are headquartered in North America.

Analysis of the results reveals that most companies score lowest in business areas that face the highest risk of corruption.

Many firms do not publicly acknowledge they face increased risks when doing business in corruption-prone markets nor do they have measures in place to identify and mitigate these risks. Few take measures to prevent corruption in ‘offsets’ – controversial sweeteners often bolted on to defence contracts – and most do little to counter the high risk of bribery associated with using agents and intermediaries to broker deals on their behalf.

Many companies score well on the quality of their internal anti-corruption measures, such as public commitments to fighting corruption and processes to prevent employees from engaging in bribery. However, because most companies publish no evidence on how these polices work in practice, it is impossible to know whether they are actually effective.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“These results reveal the defence sector remains mired in secrecy with companies often displaying inadequate policies and procedures to safeguard against corruption. With nearly three-quarters of companies failing to achieve a ‘C’ grade, clearly much more needs to be done. Given the well-established link between corruption and conflict, failure to do this will cost lives.

“Despite the overall picture looking bleak, there are some signs of progress in these results. Greater transparency and disclosure contribute to meaningful oversight and reducing corruption in the defence sector. Companies that improve both the quality and transparency of their anti-corruption efforts will see they are not only helping reduce human suffering but also aid to the promotion of the rule of law, which will benefit companies wishing to do their business in a clean way.”

The defence industry is a prime target for corruption because of the vast amount of money involved (global military expenditure in 2019 was estimated at more than $1.9 trillion), the close links between defence contracts and politics, and the notorious veil of secrecy under which the sector operates.

The impact of corruption in the arms trade is particularly serious. The value of defence contracts means that huge amounts of public money can be wasted, instead of being spent on essential services. Corruption perpetuates conflict and costs lives when troops are equipped with inadequate equipment and corrupt officials use gains from defence deals to strengthen their personal positions and undermine democracy.

The DCI provides a roadmap to better practice within the defence industry. It promotes appropriate standards of anti-corruption and transparency of policies and procedures suited to the risks faced in the defence sector. Adopting these not only reduces corporate risk, but also in turn helps to increase accountability and reduce the risk of corruption in the sector more widely.

We call on defence companies to commit to greater corporate transparency by increasing meaningful disclosures of:

- How they assess and mitigate the risks associated with operating in corruption-prone countries and publicly acknowledge the heightened risks of doing business in these markets;

- The anti-corruption programmes that are in place and the implementation of their policies and procedures;

- Measures to prevent and tackle corruption in all high-risk business areas, including the use of intermediaries, relationships with suppliers, joint ventures, offsets and interactions with public officials;

- Data that demonstrates the effectiveness of their anti-corruption programmes, such as staff surveys, audits and data regarding the use of whistleblowing hotlines and sanctions of transgressions;

Notes to editors

The DCI results can be found here – https://ti-defence.org/dci/

Global military expenditure was more than $1.9 trillion in 2019, according to SIPRI estimates – https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2020/global-military-expenditure-sees-largest-annual-increase-decade-says-sipri-reaching-1917-billion

Of the world’s 10 biggest importers of arms in 2019, eight are at high risk of corruption in the defence sector according to the DCI’s sister index – the Government Defence Integrity Index https://ti-defence.org/gdi/

Of these eight, five (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq and Qatar) are deemed to be at a ‘critical’ risk of defence sector corruption, meaning a large number of weapons are delivered to countries where they are likely to further fuel corruption, and where appropriate oversight and accountability of defence institutions is virtually non-existent.

About the Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Transparency (DCI)

The DCI analyses the commitment to transparency and anti-corruption in the world’s 134 largest defence companies.

It analyses publicly available information to assess the quality, extent and availability of anti-bribery and corruption policies and procedures in 10 key areas where increased commitment to anti-corruption ad transparency of information could reduce corruption risks in the defence industry.

The DCI does not measure corruption or how well a company’s anti-corruption measures work in practice as most disclose nothing on whether their polices and procedures are effective. A high DCI score does not indicate a company is immune to corruption – even companies with the most robust anti-corruption measures face risks and, in some cases, incidents of corruption.

The DCI follows two previous corporate indices published in 2015 and 2012, known as the Defence Companies Anti-Corruption Index. Due to significant changes in the aim, focus, methodology and question set of the 2020 index, any comparison with previous indices is not possible or appropriate.

About Transparency International – Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

+ 44 (0)79 6456 0340

New research from Transparency International Defence & Security warns of high corruption risk across CEE region

December 9 – Decades of progress towards greater democratisation across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) threatens to be undone unless urgent steps are taken to safeguard against corruption, new research from Transparency International warns.

The Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) finds more than half of the 15 countries assessed in the region face a high risk of corruption in their defence and security sectors.

Released today, Progress [Un]Made identifies region-wide issues which provide fertile ground for corruption and the deterioration of governance. These include weak parliamentary oversight of defence institutions, secretive procurement processes that hide spending from scrutiny, and concerted efforts to reduce transparency and access to information.

These issues are compounded by the huge amounts of money involved, with spiralling military expenditure in the CEE region topping US$104 billion in 2019 as many states continue to modernise their defence and security forces. The 15 states featured in the report are responsible for a quarter of this total with the majority increasing their defence budgets in the last decade.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

“Following major strides towards more robust defence governance in Central and Eastern Europe, many of these results should be a cause for concern. Corruption and weak governance in the defence and security sector is dangerous, divisive and wasteful. While it is encouraging to see a handful of countries score well the overall picture for the region is one of high corruption risk, especially around defence procurement – an area responsible for huge swathes of public spending.”

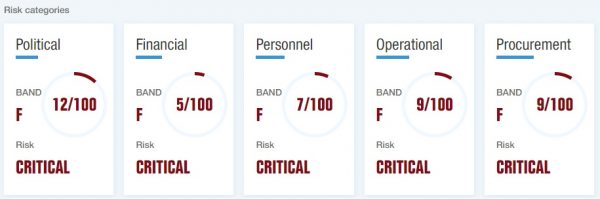

The GDI provides a detailed assessment of the corruption risks in national defence institutions by scoring each country out of 100 across five key risk areas: financial, operational, personnel, political, and procurement. Highlights from the CEE results include:

- Average score for the region is 48/100, indicating a high risk of corruption.

- Montenegro is judged to be at ‘very high’ risk with a score of 32, while Azerbaijan’s score of just 15 places it in the ‘critical’ risk category.

- High levels of transparency see Latvia fare the best in the region, with a score of 67 indicating a low risk of corruption.

- Authoritarian governments have weakened parliamentary oversight (Poland) and restricted access to information regimes (Hungary), closing off a key sector off from public debate and oversight.

We identify five key themes that are increasing corruption risk across the region, including:

Weak parliamentary oversight

Parliamentary oversight of defence is a key pillar in enforcing transparency and accountability but only two of the 15 countries we assessed have retained truly robust parliamentary oversight.

CEE regional average score: 51/100 (Moderate risk)

Best performers: 1) Latvia: 94/100 (Very low risk); 2) Lithuania: 83/100 (Very low risk)

Worst performers: 1) Azerbaijan 12/100 (Critical risk); 2) Hungary 27/100 (Very high risk)

Opaque procurement processes

Allowing companies to bid for defence contracts helps reduce the opportunities for corruption and ensure best value for taxpayers, but our analysis highlights that open competition in this area is still the exception rather than the norm.

CEE regional average score: 47/100 (High risk)

Best performers: 1) North Macedonia 82/100 (Low risk); 2) Estonia: 74/100 (Low risk)

Worst performers: 1) Azerbaijan 8/100 (Critical risk); 2) Hungary 14/100 (Critical risk)

Attacks on access to information regimes

Access to information is one of the basic principles of good governance, but national security exemptions and over-classification shield large parts of the defence sector from public view.

CEE regional average score: 55/100 (Moderate risk)

Best performers: 1) Georgia, Latvia, North Macedonia, Poland 88/100 (Very low risk); 2) Lithuania: 75/100 (low risk)

Worst performers: 1) Azerbaijan 13/100 (Critical risk); 2) Hungary 25/100 (Very high risk)

To make real progress and strengthen the governance of the defence sector in the region, Transparency International calls on governments across the region to:

- Respect the independence of parliaments and audit institutions and provide them with the information and time they need to perform their crucial oversight role.

- Overhaul their procurement systems to ensure more competition and transparency.

- Guarantee transparent and effective access to information and implement a clear rationale on the use of the national security exception, as well as transparency over how the rationale is applied.

Notes to editors:

Progress [Un]Made – Defence Governance in Central and Eastern Europe can be downloaded here.

The CEE region spent US$104 billion on defence and security in 2019. This total includes Russia, which spent US$65 billion. Lithuania and Latvia increased military spending by 232 per cent and 176 per cent respectively between 2010 and 2019, and Poland by 51 per cent over the same period. Armenia and Azerbaijan consistently spend close to 4% of GDP on defence and are among the most militarised countries in the world.

Whilst defence governance standards in Europe are some of the most robust globally, states in Central and Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, where a combination rising defence budgets and challenges to democratic institutions, are particularly vulnerable to setbacks to their recent progress in governance and development.

In Armenia, Albania, Hungary, Kosovo, Montenegro, Poland and Serbia, there is a notable tendency for parliaments to align themselves with the executive on defence matters, for example by passing executive-sponsored legislation with no or only minor amendments.

In Georgia, secret procurement accounted for 51 per cent of total procurement procedures from 2015-2017. In Ukraine that figure is 45 per cent, while in Poland it is as high as 70 per cent. In Lithuania, open competition accounted for as little as 0.5 per cent of procurement procedures, with upwards of 93 per cent of defence procurement conducted through restricted tenders and negotiated procedures.

In Hungary, the government has made it harder to access information by skewing the rules in favour of public bodies and imposing new fees on those who lodge requests. In Estonia, the 2013 access to information act contained 7 exceptions, with 1 related to defence; by 2018, there were 26 exceptions, with 7 related to defence. Just three of the 15 states we assessed – Lithuania, Latvia and Georgia – were found to have been responding to freedom of requests promptly and mostly in full.

About Transparency International

Through chapters in more than 100 countries, Transparency International has been leading the fight against corruption for the last 27 years.

About the Government Defence Integrity Index

The GDI is the only global assessment of the governance of and corruption risks in defence sectors, based upon 212 indicators in five risk categories: political, financial, personnel, operations and procurement.

The Central and Eastern Europe wave includes assessments for 15 countries: Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kosovo, Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia. All states are either EU/NATO members or accession/partner states.

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI). The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. This means overall country scores from this 2020 version cannot be accurately compared with country scores from previous iterations of the Index.

Subsequent GDI results will be released in 2021, covering Latin America, G-20 countries, the Asia Pacific region, East and Southern Africa, and NATO+.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340 (out of hours)

Two decades after the UN formally acknowledged the disproportionate and devastating impact of armed conflict on women and girls with the landmark Security Council Resolution 1325, we speak with Hon. Florence Kajuju, chair of the Commission on Administrative Justice and Secretary General of the African Ombudsman and Mediators Association, to discuss its effect and the need to integrate a gender perspective in security sector reform.

Our research shows that corruption has a detrimental effect on the efficiency of security institutions and can threaten peace and breed instability. A growing body of evidence also points to how patterns of both facilitating and tolerating corruption are gendered and are often based upon patriarchal structures and imbalances of power within societies. Fragile and insecure contexts exacerbate underlying gender dynamics that make the varied experiences of women, men, girls, and boys more visible.

The 20th anniversary of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security is a crucial reminder of the need to reaffirm the importance of including women and gender perspectives in conflict prevention, peacebuilding and governance. To mark the occasion, we interview Hon. Florence Kajuju, the Chairperson of the Commission on Administrative Justice (Office of the Ombudsman) and Secretary General of the African Ombudsman and Mediators Association (AOMA). Hon. Kajuju is an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya with over 25 years’ experience. She has previously served as a County Member of Parliament and Vice-Chairperson of the Law Society of Kenya.

Transparency International – Defence & Security: Hon. Florence Kajuju, could you please tell us what UNSC Resolution 1325 has meant for you personally and in your career?

Hon. Florence Kajuju: The passing of UNSC Resolution 1325 was a huge gain for women and it is up to us to make sure that we continue moving the agenda forward, so that we do not fail the women of this country and beyond. In my journey as an advocate at the High Court of Kenya and as a member of parliament, I have witnessed how women have struggled to be at the decision-making table, have been told to be in the kitchen rather than to vote, even though we as women make up over 50 per cent of the population. This resolution was certainly instrumental in the passing of the Kenyan Constitution in 2010, as we sought to ensure women were given equal opportunities and participate in the politics, social aspects and economics of the country. At national and county levels, we need to make sure that the Women, Peace and Security Agenda is implemented to the letter and that, in all aspects of civilian oversight, those institutions are indeed able to carry out their mandate.

Kenya also put in place a national action plan in 2016 to operationalise UNSC resolution 1325 and the Women, Peace and Security agenda. As a result of this, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) developed a gender policy. This policy has effectively increased women management in the MoD and I am pleased to report that this notably led to the appointment of the first Major General in the country, Fatuma Ahmed in 2018. Before this, as a woman if you had a child or were breastfeeding, you could be turned down from becoming a military official in recruitment processes, which are not valid reasons to not be part of the military!

I can also report on the increasing participation of women within peace committees which represent at the community level the National Steering Committee on Peace Building and Conflict Management, as a result of the UNSC resolution 1325, and which led to an increase from 14 per cent of women participation in 2013 to 29 percent in 2018. This of course isn’t enough, but it is already a success. We now also have a national budget that is gender-responsive and aims to ensure that everyone feels part of the society. This is a good thing that this country has done.

Security Sector Reform seeks to enhance the effectiveness and accountability of a country’s security sector. From your perspective, how can an understanding of underlying gender dynamics at play in conflict and insecure settings help increase the ability of the security sector to meet the range of security needs within society?

To enhance the effectiveness and accountability of our security sector, it is crucial to make sure that

everyone is given equal opportunities, in a spirit of inclusiveness. The various ways in which gender affects the security of various groups should always be considered when building reform programmes. Stereotypes within government and institutions need to be dealt with. Men and women need to be on the playing field together and both be part of the game so we are able to achieve maximum benefits. As a result, a gender perspective needs to be taken in consideration throughout the entire reform process, from the design to the planning phase and to the monitoring and evaluation phase. We certainly need to be better at this in Kenya, especially as we have numerous very good laws, but implementation is lacking. This is why institutions such as the Ombudsman office are essential in overseeing the implementation of laws and regulations.

Evidence shows that there is no effectiveness without accountability. In your view, how can integrating a gender perspective in reform programmes help rebuild security forces, in a manner consistent with democratic norms and sound principles of good governance, transparency and the rule of law?

We have a history of having a patriarchal culture in our society, of women being second-class citizens, which we have been seeking to challenge, as civilian overseers of defence and security forces in particular. We have therefore put in place a gender policy, which looks both at the internal system within the Ombudsman office but also externally at the type of complaints that are being brought to us; we’ve looked at the number of complaints that speak specifically to the intersection of gender dynamics, peace and security. One example of this has been the case of post-election violence which took place in Kenya in 2007-2008; those who were most affected by the political violence were women and children. Our role as the Ombudsman office was to make sure that beyond the complaints being dealt with, we supported the security forces in structurally taking gender consideration on board and implementing due process.

The creation of a dedicated civilian military ombudsman office in Kenya would also be a great move in this direction. It is also important for the Defence & Foreign Committee and the Administration & National Security Committee in parliament to sit down together and originate legislation or amend existing legislation to ensure a gender lens is adopted, in line with the Women, Peace and Security agenda. Once this is done across legislation, this will ease our mandate to ensure security forces abide by the law.

By Benedicte Aboul-Nasr, Project Officer, Transparency International – Defence & Security

On October 17, 2019, Lebanese citizens took to the streets in response to a government proposal to tax WhatsApp communications, in what would become known as the “Thawra”, or “Uprising” against widespread corruption and worsening economic conditions. A year after the beginning of the protests, and two months after the explosion in the Port of Beirut killed 191 people, injured over 6,500, and uprooted nearly 300,000, Lebanese citizens still have no clear answers as to why for six years, 2,700 tons of explosive chemicals were stored in hazardous conditions at the heart of Lebanon’s capital. Many suspect that a long history of negligence and corruption, the very factors that pushed people to the streets last year, are at least partly responsible for the devastation that took place on August 4, 2020.

The government response has been uneven and in the aftermath of the explosion authorities were slow to support immediate relief efforts. Instead, when Lebanese protesters took to the streets on August 8 to voice their anger towards a political class that many believe has benefited from Lebanese resources for decades, security forces responded harshly, deploying tear gas and live ammunition against protesters. Two days later, Hassan Diab’s government resigned, noting that corruption in Lebanon is “bigger than the state”. And, on August 13, eight days after the explosion, Parliament voted for a state of emergency, giving defence forces a broader mandate than the one they already had under the general mobilisation adopted to help contain COVID-19. Since then, Prime Minister-designate Mustapha Adib stepped down, within a month of his nomination, having failed to achieve the consensus necessary to form a government. At the time of writing, Lebanon remains in a political impasse, while former Prime Minister Hariri, who had stepped down two weeks into the protests in October 2019, is in the running to replace his successor.

Allegations of government corruption are not isolated incidents, and mismanagement has led to numerous crises and leadership vacuums over the years, which paved the way for the protest movement. Lebanon is now facing one of the most serious financial crises in its history which has crippled the economy. The state has defaulted on debt payments and banks are imposing de facto capital controls on withdrawals while Carnegie’s Middle East Center estimates that close to US$800 million were transferred out of the country within the first three weeks of the protests. The Lira lost 80% of its value over nine months; by July this year and Lebanon became the first country in the region to enter hyperinflation. Even before the COVID-19 crisis hit, the World Bank had estimated that up to 45% of Lebanese citizens would be below the poverty line by the end of 2020. Despite undeniable evidence that the situation was untenable, prior to the explosion, discussions with the IMF had been stalled for months, and Alain Bifani, the finance ministry’s director-general, had resigned over state officials’ unwillingness to acknowledge the scale of the crisis and achieve consensus to identify solutions. The contract for a forensic audit of the Central Bank was only signed in August, and the audit itself did not begin until September.

The international community has offered loans and significant humanitarian aid to support victims and the reconstruction of Beirut. Tellingly, several governments have pledged that they would not disburse aid through the government, and are prioritising non-governmental organisations that have been at the forefront of assessment and reconstruction needs. Aid disbursed through the government, and renewed commitments to unlock funds promised by the CEDRE conference in 2018, are conditional on stringent anti-corruption reforms being adopted and must be accompanied by strict oversight. In this regard, it is crucial that Lebanese civil society and non-profit organisations are granted access to sufficient information to oversee the disbursement of aid and prevent funds from being lost.

As part of the broader powers and responsibilities granted to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) under the state of emergency proclaimed after the explosion, the military has been given the crucial role of coordinating the distribution of humanitarian aid and supporting other public bodies in their reconstruction efforts. In carrying out these roles, and with the additional powers from which they benefit, it is crucial that the LAF ensure the highest standards of integrity and transparency with the Lebanese public. The LAF has benefitted from a high level of trust in the past, and remains one of the most representative branches of government – the institution must ensure that it maintains trust and supports ways forward for the Lebanese, in particular as Lebanese citizens and organisations rebuild.

The coming months will be crucial for Beirut’s reconstruction and to help lift Lebanon out of the crisis it is experiencing. Anti-corruption measures and transparency, not only in the disbursement of aid but also in reform efforts, should be prioritised by the armed forces themselves, and more broadly by an incoming government committed to resolve the financial and political crises Lebanon currently faces as the country seeks international support. The Lebanese Transparency Association (LTA), Transparency International’s national chapter in Lebanon, has been advocating alongside Transparency International – Defence & Security for increased transparency and accountability of the defence sector since 2018. In 2020, LTA continued to emphasise the urgent need for further transparency with constituents, and for the armed forces to implement access to information legislation to allow Lebanese citizens to understand how the body functions. As the LAF maintain responsibility in the aftermath of the explosion, both for aid disbursement and for maintaining security alongside security forces, clear communications and oversight of the defence sector are critical.

The explosion and its aftermath have brought issues that Lebanese citizens were familiar with – and which pushed many to the streets over the last year – to the forefront of Lebanon’s dealings with the international community. Only by tackling the root causes, continuing to push for reform, and beginning to rebuild institutions in which the public can trust, will Lebanon have a chance to become more stable and pave a way out of the crisis. Lebanese politicians have often shown willingness to commit to reforms when dealing with the international community in the past. However; reforms have then stalled due to a lack of consensus, for instance leading to delays in implementing access to information legislation, or in selecting members for the National Anti-Corruption Commission. As the international community aims to support Lebanese citizens and help rebuild Beirut, they should be wary of attempts to divert assistance, and of mismanagement in the disbursement of funds. Instead, any international and national initiatives should support Lebanese citizens’ calls to dismantle the root causes of corruption, for the political class to seriously address the financial crisis, and for concrete and measurable steps for reform and accountability.

Benedicte Aboul-Nasr is Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Project Officer working on Conflict and Insecurity, with a focus on the MENA region. She has a background in international humanitarian law and the protection of civilians, and currently researches links between corruption and situations of crisis and conflict.

Governance reforms, including to security sector, are urgently needed

23 October 2020 – Transparency International condemns the Nigerian state’s excessive use of force and the continued perpetration of violence against peaceful protesters.

Protests that began with demands for an end to police brutality and the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), have since transformed into wider calls for an end to corruption and the looting of public funds. The government must respond to these calls with serious evidence-based anti-corruption reforms, including to the security sector, in dialogue with civil society.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said: “The appalling violence we have seen against peaceful protestors has to end. The only way to restore the much-needed trust in relations between Nigerian citizens and the security sector is to respect and protect basic human rights. Further repressive actions against legitimate demands for an improved security sector in Nigeria will only escalate the situation.”

Nigeria’s score on the Government Defence Integrity Index by Transparency International – Defence & Security rates corruption risks in the country’s security sector as Very High, with extremely limited controls in operations and procurement. While oversight mechanisms are in place, they often lack coordination, expertise, resources, and adequate information to fully perform their role.

In addition, Nigeria has seen no significant improvement in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index since the current methodology was introduced in 2012. The 2019 Global Corruption Barometer for Africa found that Nigerians rate the police as the most corrupt institution in the country. Almost half of those surveyed reported paying a bribe to the police in the previous 12 months.

Delia Ferreira Rubio, Chair of Transparency International, said: “Corruption deprives ordinary people of their rights to peace, health, security and prosperity. It robs young people of a future in which they can fulfil their potential, and it misappropriates the wealth of a nation for the benefit of the few. Peaceful protesters exercising their right to freedom of assembly must never be met with violence and brutality. Citizens’ demands for an end to corruption must be heard and acted upon.”

Auwal Musa Rafsanjani, Executive Director of the Civil Society Legal Advocacy Centre (CISLAC), Transparency International’s national chapter in Nigeria, said: “The government of Nigeria must immediately stop deploying troops against protestors. The young people who have taken to the streets have a constitutional right to express their grievances through peaceful protest without facing violence and brutality from the state. Together with our civil society partners in Nigeria, we stand ready to work with the government on the root and branch reforms needed to the police and security agencies, and to stop the looting of public funds through corruption. We also condemn the violence and the destruction of property by groups that have infiltrated the peaceful protests.”

New report warns weak regulations leave door open to undue influence

October 21 – German defence policy risks being influenced by corporate interests, new research by Transparency International – Defence & Security warns.

Released today, Defence Industry Influence in Germany: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the German Policy Agenda details how defence companies can use their access to policymakers – secured through practices such as secretive lobbying and engagements of former public officials – to exert considerable influence over security and defence decision making.

The report finds that gaps in regulations and under-enforcement of existing rules combined with an over-reliance by the German government on defence industry expertise allows this influence to remain out of the reach of effective public scrutiny. This provides industry actors with the opportunity to align public defence policy with their own private interests.

To address these shortcomings, new controls, oversight mechanisms need to be put in place and sanctions should be applied to regulate third party influence in favour of the common good and national security.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

“Decisions and policy making related to defence and security are at particularly high risk of undue influence by corporate and private interests due to the high financial stakes, topic complexity and close relations between public officials and defence companies. Failing to strengthen safeguards and sanction those who flout the rules raises the risk that defence decision making and public funds are hijacked in favour of private interests.”

The report shows how lax rules around policymakers declaring conflicts of interest, and lack of adequate penalties for failing to disclose them, leaves the door open to MPs wishing to take up lucrative side-jobs. Frequent and prominent cases of job switches between the public and private defence sector compound issues of conflicts of interest and close personal relationships with inadequate oversight.

And, due to a lack of internal capacity, Germany’s defence institutions are increasingly outsourcing key competencies to industry, allowing defence companies crucial access to defence policy. The procurement of these external advisory services is not subject to appropriate oversight.

While the German constitution requires a strict control over excessive corporate influence in public sectors, too often this is not sufficiently exercised due to a lack of technical and human resources within government and parliament. In addition, insufficiently enforced legal regulations and a lack of transparency of lobbying activities enables undue influence to occur in the shadows outside of public scrutiny.

Greater transparency is necessary to ensure accountability

National security exemptions are common in the defence sector and enable institutions to override transparency obligations in favour of secrecy. However, protecting national security and ensuring the public’s right to information can both be achieved by striking the right balance where information is only classified based on a clear justification for secrecy. Transparency in defence is crucial to ensuring effective scrutiny in identifying and controlling undue influence.

“Despite the justification for secrecy in this policy area the greatest possible transparency must be created to ensure control by parliament and the public. If, in addition, human resources and expertise are lacking, advice from corporate lobbyists receive easy access,” said Peter Conze, security and defence expert at Transparency International Germany.

New lobbying register does not go far enough: we need a legislative footprint

The lack of transparency around lobbying in Germany allows industry actors to exert exceptional influence over public policy.

While Germany’s proposed new lobbying register provides a positive step towards transparency, it does not go far enough to allow effective scrutiny. External influence on legislative processes and important procurement decisions remains unaccountable without the publication of a legislative or decision-making footprint, which details the time, person and subject of a legislator’s contact with a stakeholder and documents external inputs into draft legislation or key procurement decisions.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is calling on the German government to:

- Expand the remit of the proposed lobbying register to cover the federal ministries and industry actors.

- Include requirements for a ‘legislative footprint’ that covers procurement decisions in addition to laws. The legislative footprint should outline the inputs and advice that have contributed to the drafting of laws or key policies, and substantially increase transparency in public sector lobbying.

- Introduce an effective and well-resourced permanent outsourcing review board within the Ministry of Defence to verify the necessity of external services and their appropriate oversight.

- Strengthen the defence expertise and capacity within the independent scientific service of the Bundestag, or to create a dedicated parliamentary body responsible for providing MPs with expertise and analysis on defence issues.

Notes to editors:

- The report “Analysis of the influence of the arms industry on politics in Germany” was prepared by Transparency International – Defence & Security with the support of Transparency International Germany.

- The report examined structures, processes and legal regulations designed to ensure transparency and control based on 30 expert interviews. The report is part of a comprehensive study of the influence of the defence industry on politics in several European countries.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

Despite promising initiatives, tackling corruption in the Nigerien security sector is still hindered by secrecy

By Flora Stevens, Project Officer – Global Advocacy

Africa’s Sahel has been plagued with conflict and insecurity for more than a decade, and the recent ramping up of violence in the region is putting already weakened armed forces under increased strain. Defence sectors across the region suffer from low levels of civilian democratic control, weak institutional oversight and are struggling to fulfil their mission to improve security in the face of a sharp uptick in attacks from non-state armed groups.

Sandwiched between jihadi militants operating in Mali and Burkina Faso to the west, Boko Haram and affiliated groups continuing to launch devastating attacks in Nigeria to the south and war-torn Libya to the north, Niger has found itself drawn into these conflicts. The complex operational requirements of bringing security to the country, with the huge distances between major settlements, porous borders and hundreds of thousands of displaced people, would pose a challenge for any armed force. But Niger, like its neighbours in the region, is also grappling with the debilitating issue of corruption in its defence sector.

Transparency International Niger has been part of the fight against corruption since 2001. The chapter works to raise public awareness of corruption issues and offers anti-corruption training to citizens. “This has enabled us to mobilise and engage citizens in the fight against corruption in our country,” said Hassane Amadou Diallo, head of the organisation. Transparency International Niger has recorded a series of major successes in its work, including a long-running advocacy campaign which culminated with Niger ratifying the United Nations Convention against Corruption in 2006, and a separate effort to abolish the ‘entrance exam’ to the civil service, a highly competitive processes which on two occasions was marred by fraud and corruption.

More recently, working with Transparency International – Defence & Security, the chapter has been involved in tackling the pernicious issue of defence corruption. Despite recent promising initiatives at national level, efforts designed to fight corruption and improve defence governance have been hindered by a high level of secrecy. It was recently revealed that almost 40% of the $312 million Niger spent on defence procurement contracts over the last three years was lost through inflated costs or materiel that was not delivered, according to a government audit of military contracts. “More than 90% of the contracts awarded to the Ministry of Defence were negotiated by direct agreement, which favoured corruptive practices and overbilling”, said Hassane Amadou. “The competition is unfair, fictitious and sometimes non-existent.” These findings came as the crisis in the Sahel continues to worsen, with hundreds of Nigerien security forces killed in fighting. At the same time, troops on the front line have complained about a lack of kit or being provided with inadequate equipment. Hassane Amadou said the audit that uncovered the extent of the procurement mismanagement would now be subject to a lengthy legal challenge. “TI Niger is hoping a fair trial will take place and that those responsible will be punished in accordance with the law,” he said.

While the findings of the audit are shocking, they unfortunately do not come as a surprise. Transparency International – Defence and Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) recently found that while government procurement regulations are clearly spelled out in law, there is a long-standing exemption for defence procurement. The 2016 Code of Public Procurements omits goods, equipment, supplies and services related to defence and security, which effectively leaves the door open to the sort of corrupt practices uncovered by the audit.

Hassane Amadou said that TI Niger has shared the main conclusions of the GDI findings with those in charge of the defence and security forces in the country. “On the basis of the GDI, we then developed an action plan targeting various stakeholders, namely the Ministry of Defence, the parliament, defence and security officials, technical and financial partners, the media and civil society,” he said.

But while there have been signs that Niger is striving to improve its security sector governance as a key pillar for future development and long-term peace and stability, the lack of emphasis on the issue of corruption could critically undermine the effectiveness and sustainability of the whole process.

Despite the impressive reform efforts of the past few years, including the 2016-2021 Renaissance Programme, the 2016 Anti-Corruption Bill, and the 2018 National Strategy to Fight Corruption, Niger is struggling to ensure their effective implementation. The Nigerien government should primarily focus on closing this gap and on rectifying loopholes that allow for corruption in the defence procurement sector to thrive. This could include revising relevant legislation to ensure it effectively applies to all defence acquisitions, with no exceptions.

It is fundamental for the Nigerien military to fully grasp the intrinsic link between corruption and operational efficiency. An important focus area must be the deployment of trained professionals to monitor corruption risks in the field. There is unfortunately currently little evidence of this. There is no pre-deployment corruption-specific training for personnel and no guidelines on addressing corruption risks during operations.

To tackle the security threats Niger is facing, mitigating corruption risks in the defence sector is paramount and requires a robust, disciplined and integrated approach on the part of the Niger government. It needs to ensure civilian oversight is strengthened through well-functioning oversight mechanisms, while making sure corruption is approached in a systemic or comprehensive manner during troop deployment.

31 July, London – In response to an announcement by the Serious Fraud Office that the agency has charged defence contractor GPT Special Project Management and three individuals after a long-running corruption investigation, Duncan Hames, Director of Policy at Transparency International UK, said:

“After more than two years of unexplained delays, it is most encouraging to see the Attorney General finally permit the Serious Fraud Office to pursue this case. These are serious allegations which involve corruption relating to a large defence contract. Failing to proceed with this would have given the impression that the UK Government condones this sort of practice.”

Notes to editors:

The UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) launched an investigation into GPT Special Project Management in August 2012.

SFO investigators requested permission to prosecute GPT from the Attorney General’s Office more than two years ago.

Transparency International UK, along with Spotlight on Corruption, wrote to the previous Attorney General, Geoffrey Cox, in October 2019 to express concern over the unexplained delays.

In January this year, courts in the UK, France and United States approved a corporate plea deal – known as a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) – which saw GPT’s parent company Airbus agree to pay £3billion in penalties after admitting to using middlemen to pay bribes to secure aircraft contracts.

With security threatened by increasingly belligerent armed actors and a hastened drawdown of international troops due to COVID-19, Iraq cannot afford to leave its defence institutions open to corruption.

By Benedicte Aboul-Nasr

Since October 2019, Iraq has seen tensions in its political sphere, including public protests, declining oil prices, increasing risks of proxy war between the US and Iran, and the resurgence of violent armed groups; the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated an already precarious security situation. After six months without a government, Iraq’s parliament appointed Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi in May 2020, and granted his full cabinet confidence in June. To respond to the state’s most urgent priorities, the incoming government and its international partners should urgently consider addressing risks of corruption and human rights violations, in particular in the defence sector, to guarantee that the defence forces have the capacity, resources, and popular backing, to respond to priorities.

In research published this week, Transparency International – Defence & Security has found Iraq’s defence sector to be at critical risk of corruption, and lacking anti-corruption and transparency mechanisms. In fact, our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) indicates that Iraq is particularly vulnerable to risks relating to finances and personnel, and does not fare much better in the areas of political, operational, and procurement corruption risks, with an overall score of 9/100 on the Index. Corruption has been linked to the erosion of institutions and of trust, and is one of the main grievances driving the protests that broke out last October. As critical as these results are, they offer the new government a blank slate to meaningfully reform the defence sector from the ground up; this will be imperative to secure longer-term security for the country.

COVID-19 has added another threat; the crisis has severely affected Iraqi citizens, as security forces enforce curfews against a backdrop of unrest and accusations of forces deliberately firing on protesters, killing over 600, injuring thousands, and recent reports of ill-treatment and torture of anti-government protesters. It is also likely to disproportionately affect displaced populations, more vulnerable to the pandemic following years of conflict and displacement, with more poorly resourced accommodation, protection, and health systems. Crucially, the pandemic has also generated additional security challenges, as the government and defence institutions redirect resources towards its pandemic response, while simultaneously countering the apparent resurgence of extremist groups. Indeed, Iraq is already facing the resurgence of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which are seeking to exploit the governance vacuum and the pandemic to resurface.

Governments around the globe have rapidly shifted their own priorities in response to COVID-19. Within weeks of the outbreak, France, Canada, the United States and several European countries in the global coalition against ISIL announced temporary withdrawals of their troops from Iraq and from NATO Mission – Iraq. Meanwhile, Operation Inherent Resolve announced that it had stopped training Iraqi security forces, as the Iraqi military also suspended its trainings to reduce the spread of the virus. Against this backdrop, ISIL has actively called for its members to ‘act’, encouraging supporters to ‘exploit disorder’ and is increasing the pace and violence of attacks, taking advantage of the drawdown of international troops.

Countering corruption risks in defence must therefore become a priority. Doing so would limit the risks of abuses of civilian populations, illegal trade of cultural property, of theft or diversion of already limited resources, and would ensure that Iraq’s defence institutions can respond to the multiple challenges it faces. Iraq has seen the consequences of a poorly governed and corrupt defence sector: the military cannot afford vulnerabilities akin to those that enabled the rise of ISIL in 2014. At the time, corruption fuelled problems which left troops hollowed out and outnumbered, such as equipment theft and ‘ghost soldiers’ – members of the military whose names were registered and salaries disbursed, without being present in military ranks. ISIL actively used these issues as recruitment tools in its propaganda, and militants developed government functions in areas where relations with government had deteriorated for years. The group benefitted more concretely from the erosion of security services, where corruption had thrived, to take over swathes of territory, leading to the prolongation of the conflict. Despite the military defeat of the group in 2018, these vulnerabilities remain and risk weakening the Iraqi armed forces when they are most needed.

Iraq’s defence institutions and oversight are severely lacking, and do not fulfil basic requirements of anti-corruption and transparency. Yet they can no longer afford a weak stance on corruption, nor on human rights. To avoid exploitation of existing vulnerabilities and erosion of the defence and security forces similar to those that led to Mosul’s fall in 2014, the government must turn its attention to defence governance, and tackle existing vulnerabilities such as those highlighted by the GDI. The incoming government is in a unique position to do so, and has already pledged to investigate the allegations of torture disclosed by the UN. The government could also take concrete steps and measures to strengthen integrity and accountability within the armed forces. In addition, both the new Defence Minister, Juma Inad, and Interior Minister, Osman Ghanimi, have extensive and highly respected military backgrounds and an in depth understanding of Iraq’s security challenges which could support reform of the defence and security sectors.

International partners have a critical role to play and should actively promote instilling anti-corruption systems into longer-term institution building and reconstruction efforts. For instance, international partners should prioritise including anti-corruption and integrity building within training courses and partnerships with the armed forces. They could also, as a means of supporting longer term development of defence institutions, support the development of accountability structures, such as streamlining a code of conduct for all military forces, developing and implementing mechanisms to allow whistle-blowing and whistle-blower protections within the armed forces, and setting up clear systems for investigations of allegations of abuse.

Armed groups in the country and its neighbourhood are becoming more belligerent, taking advantage of the pandemic and withdrawal of international forces. In this context, weeding out corruption in institutions, and strengthening anti-corruption mechanisms in the longer term, will be essential for Iraq’s government to begin restoring trust, and for armed forces to effectively respond to security threats and the resurgence of non-state belligerents.

Benedicte Aboul-Nasr is a Project Officer at Transparency International – Defence & Security. Her areas of focus are the MENA region, and how corruption affects conflict and security in the region.