Category: Industry Integrity

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence and Security, describes some of the dangers documented in our latest research paper.

Unaccountable private military and security companies continue to pursue partnerships that in recent years have led indirectly to the assassination of presidents and journalists, land grabs in conflict zones, and even suspected war crimes.

From Haiti to Saudi Arabia to Nigeria, US-based organisations – the firms that dominate the market – have found themselves associated with a string of tragedies, all while their sector has grown ever-more lucrative.

Transparency International Defence and Security’s latest research – ‘Hidden Costs: US private military and security companies and the risks of corruption and conflict – catalogues the harm playing out internationally as countries increasingly seek to outsource national security concerns to soldiers of fortune.

Hidden costs from the trade in national security

While the US and other governments have left the national security industry to grow and operate without proper regulation, the risks of conflict being exploited for monetary gain are growing all the time.

Hidden Costs documents how the former CEO of one major US private military and security company was convicted – following a guilty plea – of bribing Nigerian officials for a US$6bn land grab in the long-plundered Niger Delta.

Our research also highlights that the Saudi operatives responsible for Jamal Khashoggi’s savage murder received combat training from the US security company Tier One Group.

Arguably most damning are the accounts from Haiti, where the country’s president was killed last year by a squad of mercenaries thought to have been trained in the US and Colombia.

Pressing priority

Many governments around the world argue that critical security capability gaps are being filled quickly and with relatively minimal costs through the growing practise of outsourcing.

Spurred on by the US government’s normalisation of the trade, US firms are growing both their services and the number of fragile countries in which they operate.

The private military and security sector has swelled to be worth US$224 billion. That figure is expected to double by 2030.

The value of US services exported is predicted to grow to more than $80 billion in the near future, but the industry and the challenge faced is global.

The risks of corruption and conflict in the pursuit of profits are plain.

These risks are as old as time. But their modern manifestations in warzones must not be left to spill over. The 20-year war in Afghanistan cultivated dynamics that threaten further damage, more than a decade after governments first expressed their concerns.

Required response

International rules and robust regulation are urgently needed. We need measures that ensure mandatory reporting of private military and security company activities. The Montreux Document lacks teeth, operating as it does as guidance that is not legally binding. Code of conduct standards must also become mandatory for accreditation, rather than purely voluntary.

Most private military and security firms are registered in the US. So Transparency International Defence and Security is also calling on Congress to take a leading role in pushing through meaningful reforms under its jurisdiction. There is an opportunity arriving in September, when draft legislation faces review.

Policymakers have long been aware of the corruption risks and the related threats to peace and prosperity posed by this sector. The time for action is well overdue. No more Hidden Costs.

Transparency International Defence & Security will release the full results of its Government Defence Integrity Index on Tuesday, November 16 at 00.01 CET.

The Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) is the only global assessment of corruption risks in the defence and security sector. It provides a snapshot of the strength of anti-corruption safeguards in 86 countries.

More on the GDI: https://ti-defence.org/gdi/about/

The GDI highlights a worrying lack of safeguards against corruption in defence and security sectors worldwide. It also shows countries contributing to or leading major international interventions lack key anti-corruption measures in their overseas operations.

Full results and scores for countries will be published here at 00.01 CET on Tuesday, November 16: https://ti-defence.org/gdi/map/

To request interviews or press materials under embargo until publication, please email the Transparency International UK press office press@transparency.org.uk

May 6, 2021 – Close links between the defence industry and governments in Europe are jeopardising the integrity and accountability of national security decisions, according to a new report by Transparency International – Defence and Security.

Defence Industry Influence on Policy Agendas: Findings from Germany and Italy explores how defence companies can influence policy through political donations, privileged meetings with officials, funding of policy-focused think tanks and the ‘revolving door’ between the public and private sector.

These ‘pathways’ can be utilised by any business sector, but when combined with the huge financial resources of the arms industry and the veil of secrecy under which much of the sector operates, they can pose a significant challenge to the integrity and accountability of decision-making processes – with potentially far-reaching consequences.

This new study calls on governments to better understand the weaknesses in their systems that can expose them to undue influence from the defence industry, and to address them through stronger regulations, more effective oversight and increased transparency.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence and Security, said:

“When individuals, groups or corporations wield disproportionate or unaccountable influence, decisions around strategy and expenditure can be made to benefit private interests rather than the public good. In defence, this can lead to ill-equipped armed forces, the circumvention of arms export controls, and contracts that line the pockets of defence companies at the public’s expense.

“The defence and security sectors are a breeding ground for hidden and informal influence. Huge budgets and close political ties, combined with high levels of secrecy typical of issues deemed to be of national security, means these sectors are particularly vulnerable. Despite the serious risk factors, government oversight systems and regulations tend to be woefully inadequate, allowing undue influence to flourish, with a lot to gain for those with commercial interests.”

Transparency International – Defence and Security calls on states to implement solutions to ensure that their defence institutions are working for the people and not for private gain.

Measures such as establishing mandatory registers of lobbyists, introducing a legislative footprint to facilitate monitoring of policy decisions, strengthening conflict of interest regulations and their enforcement, and ensuring a level of transparency that allows for effective oversight, will be important steps towards curbing the undue influence of industry over financial and policy decisions which impact on the security of the population.

Notes to editors:

Defence Industry Influence on Policy Agendas: Findings from Germany and Italy is based on two previous reports which take an in-depth look at country case studies. The two countries present different concerns:

- In Italy, the government lacks a comprehensive and regularly updated defence strategy, and thus tends to work in an ad hoc fashion rather than systematically. A key weakness is a lack of long-term financial planning for defence programmes and by extension, oversight of the processes of budgeting and procurement.

- In Germany, despite robust systems of defence strategy formation and procurement, significant gaps in capabilities have led to an overreliance on external technical experts, opening the door to private sector influence over key strategic decisions.

The German report can be found here and the Italian report here.

The information, analysis and recommendations presented in the case studies were based on extensive document review and more than 50, mainly anonymous, interviews.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340 (out of hours)

New report warns close relationships and weak regulations leave door open to undue influence

28 April, 2021 – A close relationship between the defence industry and the Italian government jeopardises the integrity and accountability of the political decision-making process, according to new research by Transparency International – Defence and Security.

Released today, Defence Industry Influence in Italy: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the Italian Policy Agenda details how defence companies can use their access to policymakers to exert considerable influence over defence and security decision-making in Italy.

The report, prepared by Transparency International – Defence and Security with the support of the Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (CILD) and Osservatorio Mil€x sulle spese militari, invites the Italian government to understand better the weaknesses of its system such as to expose the decision-making process to undue influence by the defence industry, as well as to address them through more stringent regulations, more effective control and greater transparency.

In particular, Transparency International, Osservatorio Mil€x and CILD call on the Italian government to:

- Establish a process to publish and review a regular, clear and comprehensive national defence strategy with meaningful participation of different stakeholders including civil society.

- Introduce a new law to regulate lobbying and implement a mandatory stakeholder public register, with clear definitions and a public agenda of meetings between stakeholders and authorities, to allow full scrutiny.

- Widen the scope and applicability of ‘revolving door’ regulations to prevent conflicts of interest and reduce opportunities for undue influence

- Increase transparency in the export licensing process to allow for full and meaningful oversight.

Notes to editors:

- The full press release, in Italian, is available here.

- The report “Defence Industry Influence in Italy: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the Italian Policy Agenda” was prepared by Transparency International – Defence & Security with the support of Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (CILD) and Osservatorio Mil€x sulle spese militari.

- The report examines the structures, processes and legal regulations designed to ensure transparency and control based on 20 expert interviews. The report is part of an overarching study of the influence of the defence industry on politics in several European countries.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

By Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy – Transparency International Defence & Security

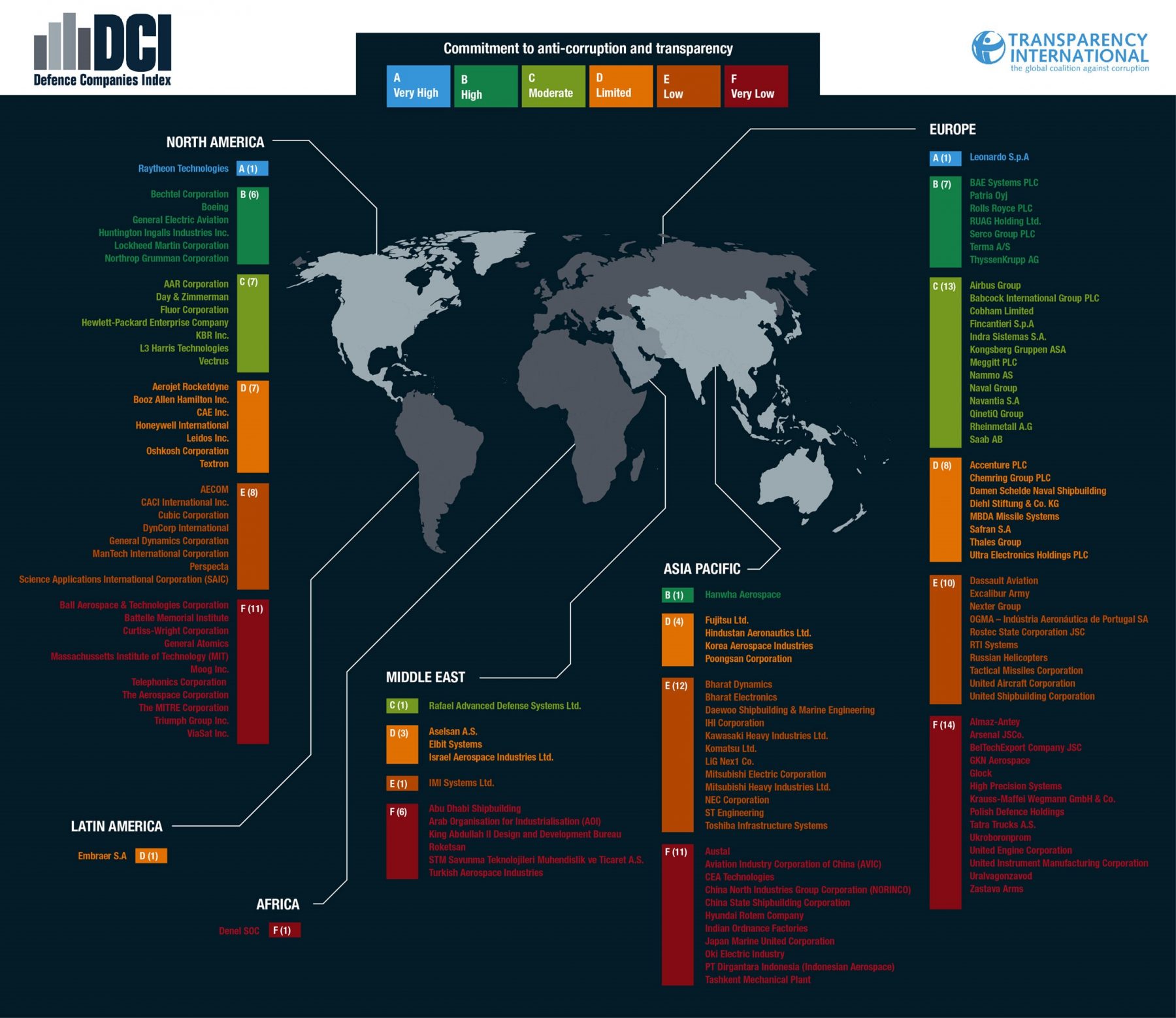

Nearly three-quarters of the world’s largest defence companies show little to no commitment to tackling corruption. That’s the headline finding from our newly published Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI). It assesses 134 of the world’s leading arms companies, ranking their policies and approach to fighting corruption from A to F.

The statistic is deeply concerning, if not altogether surprising to those familiar with the defence industry. Reducing corruption in the defence sector is imperative to guarantee safety and security. Yet, a veil of secrecy, invoked ostensibly in the interests of national security, shrouds the defence sector’s activities making it especially vulnerable. The widespread use of middlemen, whose identities and activities are kept secret, further limits oversight. The impact of corruption in the arms trade is particularly pernicious. The high value of defence contracts means that huge amounts of public money may be wasted, instead of being spent on essential public services. Corruption can encourage the excessive accumulation of arms, increase the circumvention of arms controls and facilitate the diversion of arms consignments to unauthorized recipients, perpetuating conflict and costing lives and undermining democracy.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, of the world’s 10 largest importers of major arms between 2015-2019, eight countries – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq and Qatar, UAE, China and India – are at high, very high or critical of corruption in the defence sector as measured by our Government Defence Integrity Index, the DCI’s sister index. Critical risk of defence sector corruption means major arms are sold to countries where they are likely to further fuel corruption, and where appropriate oversight and accountability of defence institutions is virtually non-existent.

The findings of the DCI add to this worrying picture. Nearly two thirds (61%) of the companies assessed show no clear evidence of policies or processes to assess and manage risk in markets they operate in. In addition, only 10% of the companies actively disclose full details of countries in which they and their subsidiaries operate, leaving a major gap in transparency and oversight of corporate activity.

Click here to view full screen.

The DCI has revealed that many companies score well on the quality of their internal anti-corruption measures, such as public commitments to fighting corruption and processes to prevent employees from engaging in bribery. However, because most companies publish no evidence on how these policies work in practice, it is impossible to know whether they are actually effective. Many firms do not publicly acknowledge they face increased risks when doing business in corruption-prone markets nor do they have apparent measures in place to identify and mitigate these risks. Few take measures to prevent corruption in ‘offsets’ – controversial side deals that involve a company reinvesting some of the proceeds of an arms deal into the customer’s economy but are banned in other sectors because of the corruption risks such deals pose – and most do little to counter the high-risk of bribery associated with using agents and intermediaries to broker deals on their behalf.

It is essential that companies have procedures in place to deal with these often opaque and high-risk aspects of the defence sector – including agents and intermediaries, joint ventures, offset contracting and operating in geographies considered at high risk of corruption.

We urge defence companies to increase corporate transparency through meaningful disclosures of:

- their corporate political engagement – a particularly high-risk issue in the defence sector -including their political contributions, charitable donations, lobbying and public sector appointments for all jurisdictions in which they are active;

- their procedures and the steps taken to prevent corruption in the highest risk areas, such as their supply chain, agents and intermediaries, joint ventures and offsets;

- procedures for the assessment and mitigation of corruption risks associated with operating in high-risk markets, a major risk for defence companies, as well as acknowledgement of the corruption risks associated with such practices;

- beneficial ownership and advocate for governments to adopt data standards on beneficial ownership transparency;

- all fully consolidated subsidiaries and non-fully consolidated holdings, and to state publicly that they will not work with businesses which operate with deliberately opaque structures; and

- the nature of work, their countries of operation and the countries of incorporation of their fully consolidated subsidiaries and non-fully consolidated holdings.

The DCI provides a roadmap for better practice within the defence industry. It promotes appropriate standards of anti-corruption and transparency of policies and procedures suited to the risks faced in the defence sector. Adopting these will not only reduce corporate risk, but also increase accountability and reduce the risk of corruption in the sector more widely.

ARMS INDUSTRY MUST DO MORE TO IMPROVE QUALITY AND TRANSPARENCY OF ANTI-CORRUPTION MEASURES

February 9, 2021 – Nearly three-quarters of the world’s largest defence companies show little to no commitment to tackling corruption, new research from Transparency International reveals.

The Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Corporate Transparency (DCI) is the only global index that measures the commitment to transparency and anti-corruption of the world’s leading defence companies.

Key findings:

- Just 12% (16) of the 134 companies assessed receive a top ‘A’ or ‘B’ ranking, demonstrating a high level of commitment to anti-corruption.

- 73% (98) received a ‘D’ or lower, indicating little commitment to transparency and anti-corruption.

- Of the 36 companies that scored a ‘C’ or higher, 21 are based in Europe and 13 are headquartered in North America.

Analysis of the results reveals that most companies score lowest in business areas that face the highest risk of corruption.

Many firms do not publicly acknowledge they face increased risks when doing business in corruption-prone markets nor do they have measures in place to identify and mitigate these risks. Few take measures to prevent corruption in ‘offsets’ – controversial sweeteners often bolted on to defence contracts – and most do little to counter the high risk of bribery associated with using agents and intermediaries to broker deals on their behalf.

Many companies score well on the quality of their internal anti-corruption measures, such as public commitments to fighting corruption and processes to prevent employees from engaging in bribery. However, because most companies publish no evidence on how these polices work in practice, it is impossible to know whether they are actually effective.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“These results reveal the defence sector remains mired in secrecy with companies often displaying inadequate policies and procedures to safeguard against corruption. With nearly three-quarters of companies failing to achieve a ‘C’ grade, clearly much more needs to be done. Given the well-established link between corruption and conflict, failure to do this will cost lives.

“Despite the overall picture looking bleak, there are some signs of progress in these results. Greater transparency and disclosure contribute to meaningful oversight and reducing corruption in the defence sector. Companies that improve both the quality and transparency of their anti-corruption efforts will see they are not only helping reduce human suffering but also aid to the promotion of the rule of law, which will benefit companies wishing to do their business in a clean way.”

The defence industry is a prime target for corruption because of the vast amount of money involved (global military expenditure in 2019 was estimated at more than $1.9 trillion), the close links between defence contracts and politics, and the notorious veil of secrecy under which the sector operates.

The impact of corruption in the arms trade is particularly serious. The value of defence contracts means that huge amounts of public money can be wasted, instead of being spent on essential services. Corruption perpetuates conflict and costs lives when troops are equipped with inadequate equipment and corrupt officials use gains from defence deals to strengthen their personal positions and undermine democracy.

The DCI provides a roadmap to better practice within the defence industry. It promotes appropriate standards of anti-corruption and transparency of policies and procedures suited to the risks faced in the defence sector. Adopting these not only reduces corporate risk, but also in turn helps to increase accountability and reduce the risk of corruption in the sector more widely.

We call on defence companies to commit to greater corporate transparency by increasing meaningful disclosures of:

- How they assess and mitigate the risks associated with operating in corruption-prone countries and publicly acknowledge the heightened risks of doing business in these markets;

- The anti-corruption programmes that are in place and the implementation of their policies and procedures;

- Measures to prevent and tackle corruption in all high-risk business areas, including the use of intermediaries, relationships with suppliers, joint ventures, offsets and interactions with public officials;

- Data that demonstrates the effectiveness of their anti-corruption programmes, such as staff surveys, audits and data regarding the use of whistleblowing hotlines and sanctions of transgressions;

Notes to editors

The DCI results can be found here – https://ti-defence.org/dci/

Global military expenditure was more than $1.9 trillion in 2019, according to SIPRI estimates – https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2020/global-military-expenditure-sees-largest-annual-increase-decade-says-sipri-reaching-1917-billion

Of the world’s 10 biggest importers of arms in 2019, eight are at high risk of corruption in the defence sector according to the DCI’s sister index – the Government Defence Integrity Index https://ti-defence.org/gdi/

Of these eight, five (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq and Qatar) are deemed to be at a ‘critical’ risk of defence sector corruption, meaning a large number of weapons are delivered to countries where they are likely to further fuel corruption, and where appropriate oversight and accountability of defence institutions is virtually non-existent.

About the Defence Companies Index on Anti-Corruption and Transparency (DCI)

The DCI analyses the commitment to transparency and anti-corruption in the world’s 134 largest defence companies.

It analyses publicly available information to assess the quality, extent and availability of anti-bribery and corruption policies and procedures in 10 key areas where increased commitment to anti-corruption ad transparency of information could reduce corruption risks in the defence industry.

The DCI does not measure corruption or how well a company’s anti-corruption measures work in practice as most disclose nothing on whether their polices and procedures are effective. A high DCI score does not indicate a company is immune to corruption – even companies with the most robust anti-corruption measures face risks and, in some cases, incidents of corruption.

The DCI follows two previous corporate indices published in 2015 and 2012, known as the Defence Companies Anti-Corruption Index. Due to significant changes in the aim, focus, methodology and question set of the 2020 index, any comparison with previous indices is not possible or appropriate.

About Transparency International – Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

+ 44 (0)79 6456 0340

New report warns weak regulations leave door open to undue influence

October 21 – German defence policy risks being influenced by corporate interests, new research by Transparency International – Defence & Security warns.

Released today, Defence Industry Influence in Germany: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the German Policy Agenda details how defence companies can use their access to policymakers – secured through practices such as secretive lobbying and engagements of former public officials – to exert considerable influence over security and defence decision making.

The report finds that gaps in regulations and under-enforcement of existing rules combined with an over-reliance by the German government on defence industry expertise allows this influence to remain out of the reach of effective public scrutiny. This provides industry actors with the opportunity to align public defence policy with their own private interests.

To address these shortcomings, new controls, oversight mechanisms need to be put in place and sanctions should be applied to regulate third party influence in favour of the common good and national security.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

“Decisions and policy making related to defence and security are at particularly high risk of undue influence by corporate and private interests due to the high financial stakes, topic complexity and close relations between public officials and defence companies. Failing to strengthen safeguards and sanction those who flout the rules raises the risk that defence decision making and public funds are hijacked in favour of private interests.”

The report shows how lax rules around policymakers declaring conflicts of interest, and lack of adequate penalties for failing to disclose them, leaves the door open to MPs wishing to take up lucrative side-jobs. Frequent and prominent cases of job switches between the public and private defence sector compound issues of conflicts of interest and close personal relationships with inadequate oversight.

And, due to a lack of internal capacity, Germany’s defence institutions are increasingly outsourcing key competencies to industry, allowing defence companies crucial access to defence policy. The procurement of these external advisory services is not subject to appropriate oversight.

While the German constitution requires a strict control over excessive corporate influence in public sectors, too often this is not sufficiently exercised due to a lack of technical and human resources within government and parliament. In addition, insufficiently enforced legal regulations and a lack of transparency of lobbying activities enables undue influence to occur in the shadows outside of public scrutiny.

Greater transparency is necessary to ensure accountability

National security exemptions are common in the defence sector and enable institutions to override transparency obligations in favour of secrecy. However, protecting national security and ensuring the public’s right to information can both be achieved by striking the right balance where information is only classified based on a clear justification for secrecy. Transparency in defence is crucial to ensuring effective scrutiny in identifying and controlling undue influence.

“Despite the justification for secrecy in this policy area the greatest possible transparency must be created to ensure control by parliament and the public. If, in addition, human resources and expertise are lacking, advice from corporate lobbyists receive easy access,” said Peter Conze, security and defence expert at Transparency International Germany.

New lobbying register does not go far enough: we need a legislative footprint

The lack of transparency around lobbying in Germany allows industry actors to exert exceptional influence over public policy.

While Germany’s proposed new lobbying register provides a positive step towards transparency, it does not go far enough to allow effective scrutiny. External influence on legislative processes and important procurement decisions remains unaccountable without the publication of a legislative or decision-making footprint, which details the time, person and subject of a legislator’s contact with a stakeholder and documents external inputs into draft legislation or key procurement decisions.

Transparency International – Defence & Security is calling on the German government to:

- Expand the remit of the proposed lobbying register to cover the federal ministries and industry actors.

- Include requirements for a ‘legislative footprint’ that covers procurement decisions in addition to laws. The legislative footprint should outline the inputs and advice that have contributed to the drafting of laws or key policies, and substantially increase transparency in public sector lobbying.

- Introduce an effective and well-resourced permanent outsourcing review board within the Ministry of Defence to verify the necessity of external services and their appropriate oversight.

- Strengthen the defence expertise and capacity within the independent scientific service of the Bundestag, or to create a dedicated parliamentary body responsible for providing MPs with expertise and analysis on defence issues.

Notes to editors:

- The report “Analysis of the influence of the arms industry on politics in Germany” was prepared by Transparency International – Defence & Security with the support of Transparency International Germany.

- The report examined structures, processes and legal regulations designed to ensure transparency and control based on 30 expert interviews. The report is part of a comprehensive study of the influence of the defence industry on politics in several European countries.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

31 July, London – In response to an announcement by the Serious Fraud Office that the agency has charged defence contractor GPT Special Project Management and three individuals after a long-running corruption investigation, Duncan Hames, Director of Policy at Transparency International UK, said:

“After more than two years of unexplained delays, it is most encouraging to see the Attorney General finally permit the Serious Fraud Office to pursue this case. These are serious allegations which involve corruption relating to a large defence contract. Failing to proceed with this would have given the impression that the UK Government condones this sort of practice.”

Notes to editors:

The UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) launched an investigation into GPT Special Project Management in August 2012.

SFO investigators requested permission to prosecute GPT from the Attorney General’s Office more than two years ago.

Transparency International UK, along with Spotlight on Corruption, wrote to the previous Attorney General, Geoffrey Cox, in October 2019 to express concern over the unexplained delays.

In January this year, courts in the UK, France and United States approved a corporate plea deal – known as a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) – which saw GPT’s parent company Airbus agree to pay £3billion in penalties after admitting to using middlemen to pay bribes to secure aircraft contracts.

By Colby Goodman

This post first appeared in the March 2020 edition of The Export Practitioner.

Sometimes good intentions are just good intentions. In the push for major changes to the U.S. arms export control system from 2010-13, the Obama administration often said the U.S. government was not effectively preventing harmful arms exports. One major culprit was “an overly broad definition of what should be subject to export classification and control,” according to then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates.

Placing “higher walls around fewer, more critical items” would solve the problem. Seven years later, however, there are serious questions about whether there are higher walls around military technologies important in modern warfare.

Push for Higher Walls

Gates’s concern about the overly broad definition of arms was based on his time as deputy director for intelligence at the Central Intelligence Agency. In his April 20, 2010, speech, Gates said, “it soon became apparent that the length of the list of controlled technologies outstripped our finite intelligence monitoring capabilities and resources. It had the effect of undercutting our efforts to control the critical items.”

A few State officials also told me at the time that they had been requested to do investigations (post-export end-use checks) on U.S.-approved exports of items such as washers for certain weapons systems, which they thought was a waste of time.

The Obama administration in fact frequently stated that the U.S. arms export control system was harmful because “we devote[d] the same resources to protecting M1A1 tank brake pads as we do to protecting the M1A1 tank itself.”

According to Gates, “many parts and components of a major piece of defense equipment – such as a combat vehicle or aircraft – require their own export licenses. It makes little sense to use the same lengthy process to control the export of every latch, wire, and lug nut for a piece of equipment like the F-16, when we have already approved the export of the whole aircraft.” Instead, the U.S. government should focus on the five percent of cases that are riskier.

While the administration often exaggerated these points – M1A1 tanks had always received much more vetting than their brake pads – many parts and components did require a separate license. In 2011, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) also published a report that highlighted clear gaps in State post-export end-use checks for sensitive night vision goggles to countries in the Middle East.

In response, the Obama administration led an effort to move an estimated 30,000 munitions-related items from State’s more strictly controlled U.S. Munitions List (USML) to Commerce’s more loosely controlled Commerce Control List (CCL). This effort included up to 90 percent of the items controlled under the USML’s military vehicle category.

For the military aircraft category, “missile launchers, radar warning receivers, and laser/missile warning systems” would continue to be controlled under the USML. However, items such as F-16 wings, rudders, fuel tanks, and landing gear would move to the CCL. The administration would also move some items formerly classified as significant military equipment.

But, did the Obama administration simultaneously elevate reviews or checks on key U.S. military technologies that stayed on the USML? It certainly was not enough for the Obama administration to just move tens of thousands of munitions off the USML. There was also a risk that the move would likely result in a dip in State revenue and personnel for examining arms exports.

Gaps in Implementation

In a recently published report entitled Holes in the Net: U.S. Arms Export Control Gaps in Combatting Corruption, I argue that there are a number of gaps in State’s efforts to place higher walls around arms on the USML. These gaps are in State’s Directorate for Defense Trade Control’s (DDTC) basic review of arms export licenses and in their more detailed pre- and post-export end-use checks. The problems appear to have been widened under the Trump administration.

In July 2018, for instance, State’s Inspector General (IG) found several weaknesses in the way DDTC reviews arms export applications in an audit. Specifically, the IG found that DDTC had “approved 20 of the 21 applications (95 percent) [IG] reviewed despite lacking required information…” (see The Export Practitioner, March 2019, page 15).

In eight cases, the IG found inconsistencies within the application on the quantities, types of arms, or values, which are indicators of a possible diversion of U.S. weapons or bribery. The IG audit also found 17 cases in which DDTC should have notified Congress for additional scrutiny, but DDTC did not.

State is no longer increasing the number of its end-use checks in a year. In the department’s annual report on end-use checks for fiscal year (FY) 2016, DDTC said there was an increase in the percentage of end-use checks they initiated compared to the total export applications for the year from 1.3 percent in FY 2015 to 1.75 percent in FY 2016.

DDTC seemed to indicate that this increase showed it was beginning to elevate its reviews of more sensitive military items. However, the most recent end-use report for FY 2018 under the Trump administration shows a drop in the percentage of end-use checks to 1.3 percent, which is similar to percentage levels before the reform started.

There are also some key gaps in the way DDTC conducts its end-use checks. In 2016, State developed a new framework for reviewing arms sales, which recommend asking several key questions about corruption. These questions include whether or not the intended recipient of U.S. arms is “permitting illicit trafficking across borders, buying and selling positions or professional opportunities, stealing government assets and resources, engaging in bribery, or maintaining rolls of ghost personnel.” However, DDTC does not regularly look at the above defense sector corruption indicators when conducting its pre-export end-use checks.

It also appears there have been some challenges with DDTC’s post-export end-use checks. In the department IG’s audit of DDTC in 2018, they noted serious delays, from 77 to 300 days, in conducting post-export end-use checks. In FY 2018, DDTC had also only conducted around nine pre- or post-export end-use checks for all arms exports to the Middle East and North Africa despite the ongoing risks of diversion in the region.

What could be done to elevate State checks on key military technologies and weapons systems? DDTC has said one of the key reasons for some of the above gaps has been staff turnover and an overall staff reduction. DDTC told the department’s IG that its licensing office had a 28 percent reduction in staffing as of July 2018, and some licensing officers were finding it difficult to keep up with their workload. Staff turnover also made it difficult for DDTC to conduct end-use checks in the Middle East in FY 2018.

Fixing the Gaps

While DDTC has hired some staff to help address the gaps in end-use checks for the Middle East, they still have not been able to add enough staff to address all of the above concerns. The Trump administration’s hiring freeze and reductions in State funding have also impacted DDTC’s efforts to hire new staff. Congress, however, could address this gap by elevating funding for DDTC personnel, which would also help speed up DDTC’s review of arms export applications generally.

It also appears that the Trump administration’s focus on increasing the number of U.S. arms sales to key U.S. partners and allies around the world has impacted some State focus on enhancing risk assessments. There, however, are continuing efforts to enhance these risk assessments at State, including related to defense sector corruption indicators.

In some ways, Gates was right when he said there was a need to place higher walls around key U.S. military technologies and weapons systems to prevent them from reaching the wrong hands. If the United States does want to make good on one of its initial reasons for the reform, there are still opportunities to do so. Without these improvements, however, the United States will be back where it started at the beginning of the reform, not effectively preventing harmful arms exports.

(c) 2020 Gilston-Kalin Communications LLC. Reprinted with permission.

January 14, 2020 – Sweeping reforms to controls on American arms sales abroad are increasing holes in checks to identify and curb corruption – measures that can also be used to assess whether sales may help or hurt efforts to address terrorist threats and attacks – according to new research by Transparency International Defense & Security.

Launched today, Holes in the Net assesses the current state of US arms export controls by examining corruption risk in three of the most prominent sales programs, which together authorized at least $125 billion in arms sales worldwide for fiscal year 2018.

Across all three different arms sales programs, which are managed by the Defense, State, and Commerce Departments, there is a clear gap in American efforts to assess critical, known corruption risk factors. This include the risks of corrupt practices – such as theft of defense resources, bribery, and promoting military leaders based on loyalty instead of merit – weakening partner military forces.

The United States is one of the biggest arms exporters to countries identified as facing ‘critical’ corruption risk in their defense sector, including Egypt, Jordan, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, according to recent analysis by Transparency International – Defense & Security.

Steve Francis OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defense & Security, said:

“Given the corrosive effect corruption has on military effectiveness and legitimacy, it is deeply concerning to see that these reforms to American arms export controls have made it easier for practices like bribery and embezzlement to thrive. In order to ensure American arms sales do not fuel corruption in countries like Egypt, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, it is imperative to understand and mitigate the corruption risks associated with countries receiving US-made weapons before approving major arms deals.”

Of the three programs assessed in the report – Foreign Military Sale, Direct Commercial Sale, and the 600 Series – the 600 Series was identified as having the biggest gaps in its anti-corruption measures. Overseen by the Commerce Department, sales through this program do not require declarations on a series of major corruption risk areas, including on certain arms agents or brokers, political contributions, company subsidiaries and affiliates, and any defense offsets. These areas are common conduits used for bribery and political patronage.

More recently, the Trump administration has proposed moving many types of semi-automatic firearms and sniper rifles to Commerce Department oversight. The proposal calls for additional controls for firearms, but also reduces overall oversight of small and light weapons exports.

Colby Goodman, Transparency International – Defense & Security consultant and author of the report, said:

“Over the past 30 years, America has established some of the strongest laws to prevent bribery and fraud by defense companies engaged in arms sales. However, defense companies selling arms through the 600 Series program no longer have to comply with key anti-corruption requirements. As a result, US officials will likely find it harder to identify and curb bribery and fraud in sales of arms overseen by the Commerce Department.”

The report analyzed five priority corruption risk factors for American arms sales programs: 1) Ill-defined and unlikely military justification; 2) Undisclosed or unfair promotions and salaries in recipient countries; 3) Under-scrutinized and illegitimate agents, brokers and consultants; 4) Ill-monitored and under-publicized defense offset contracts, and 5) Undisclosed, mismatched or secretive payments.

The report makes a series of policy recommendations that would help strengthen anti-corruption measures in these prominent arms sale programs, including:

- Creating a corruption risk framework for assessing arms sales through programs managed by the Defense, State, and Commerce Departments. These assessment frameworks must examine key risk factors identified in our report, including theft of defense resources and promoting military leaders based on loyalty instead of merits, among others.

- Strengthening defense company declarations and compliance systems for sales of arms overseen by the Commerce Department, including declarations of any defense company political contributions, marketing fees, commissions, defense offsets, and financiers and insurance brokers of arms – all clear conduits for corruption.

- Increasing transparency on arms sales and actions to combat arms trafficking overseen by the Defense, State, and Commerce Department. Critically, the Defense and State Departments need more details on defense offsets in order to properly review proposed arms sales. There is virtually no information on Commerce Department approved arms sales.

- Legislation requiring for firearms and associated munitions to remain categorized as munitions to ensure further relaxing of export controls do not adversely impact US national security or foreign policy objectives.

Notes to editors:

Interviews are available with the report author.

Holes in the Net is available to download here.

Saudi Arabia, a major importer of US-made arms, failed to defend against an attack on its oil facilities in September 2019. Reports have suggested that corrupt ‘coup-proofing’ measures designed to shield the ruling family likely contributed to the ineffective response.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340

Last week, Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) attended the Fifth Annual Conference of States Parties (CSP5) to The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), where delegations of the 104 signatories gathered to review the status of the Treaty and set the agenda for the year ahead.

Five years since the introduction of the Arms Trade Treaty, there are plenty of reasons for gloom. This year’s Conference focused on two topics in particular: diversion and gender-based violence. Despite being covered under the ATT – articles 7 and 11 respectively – states have been struggling to address these illicit arms flows and reduce gender-based violence. Any advances made by new states ratifying the treaty – most recently Canada and Botswana – have been countered by the lack of representation from some of the world’s largest arms exporters such as Russia, China and now the US, which withdrew its signature from the treaty.

Meanwhile transfers of weapons continue to increase, and implementation challenges are becoming obvious. However, at this point the question is not one of giving up, but rather one of what can we do to make the Treaty more effective?

The CSP is open to civil society, encouraging participation in side events and lively debates. Only one panel discussion was restricted to state signatories – out of 20 in total. While this shows the role and importance of civil society participation in the ATT process, more can be done to foster this cooperation during the rest of the year.

TI-DS has an important contribution to make to this movement. By working together with Transparency International’s national chapters and other local partners we can do more to support national adoption and implementation strategies.

What does that mean in practice? Here are five learnings from the CSP5 that point the way:

1. Provide the evidence-base for arms control decisions

When deciding whether to approve an arms export application, state licensing bodies must consider a wide range of factors about the importing country – from the internal security situation to regional stability and risk of diversion from the stated end-user. Most states will assess these factors through an in-depth risk assessment of the viability of the export, using both classified and open source information.

Research reports and studies conducted by civil society can provide valuable sources of information for states. TI’s Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI) provides an analysis of the corruption risks within the defence establishments of 90 countries worldwide. Government export control agencies can use this data to consider the risk of corruption in importing countries to inform the likelihood of diversion or misuse of weapons.

2. Raise awareness of the ATT and its relevance to national governments

As organisations with a particular national, regional or thematic focus, civil society organisations (CSO) are well-placed to provide expert insight into the arms control issues facing a country. In states that have not yet adopted the ATT – or are working towards ratifying it – CSOs can work with government agencies, industry and think tanks to facilitate a national debate on the importance and benefits of compliance with the treaty. They can build coalitions of interested parties to work towards a common goal, as shown by the continued contribution made by the Control Arms Coalition.

Moreover, civil society – unlike governments, industry or think tanks – often have the grassroots networks and community buy-in needed to build pressure and hold states to account for their promises when it comes to international obligations such as the ATT.

3. Assist parliaments and governments in implementing the treaty

CSOs working on arms control issues are in general able to develop a broader knowledge base than parliamentarians and other actors whose day jobs only touch upon this complex topic. The potential for cooperation between the two was illustrated by an example presented at this year’s conference which highlighted the role of the Small Arms Survey NGO, who assisted Japan by conducting a gap analysis of its ATT implementation progress.

From giving evidence to a parliamentary committee to providing MPs with research to inform parliamentary questions, CSOs can work directly with concerned parliamentarians to maintain the political will and internal pressure needed to support proper implementation of the treaty.

4. Monitor ATT progress and violations

As third-party stakeholders, CSOs are often able to raise and address controversial topics.

CSOs working in-country may encounter evidence of a violation of treaty obligations and report it to the government. Many CSOs also have the ability and expertise to synthesise these cases into national and regional trends, thereby providing governments with a tool to develop mitigation strategies and improve their progress in implementing the ATT.

By providing a solid evidence base with clear policy recommendations, CSOs can help states reflect on the progress they have made and highlight areas that need strengthening.

5. Achieve universalisation through improved reporting and transparency

The substantial differences in the way that states submit their ATT reporting obligations constitute a barrier to universalisation. Although 83 per cent of states used the reporting template, some are still submitted incomplete or in non-readable format or indeed in a completely different format that is difficult to consolidate. On top of this, 25 per cent of states failed to submit an annual report at all.

CSOs can work with national governments and industry to promote transparency and common reporting standards, which in turn allows for comparability and more effective implementation of treaty obligations.

The future of the ATT may be uncertain, but states can’t do it alone and nor should they. Civil society can help national governments bridge the gap between policy and practice by providing hands-on insight and analysis into arms control issues worldwide.

Transparency International Defence & Security would like to announce the initial phase of the 2019 edition of the Defence Companies Anti-Corruption Index (DCI).

Update: Following a thorough review of the company feedback, we will now begin the assessments in May 2019 to account for company reporting periods.

What is the Defence Companies Anti-Corruption Index (DCI)?

The DCI sets standards for transparency, accountability and anti-corruption programmes in the defence sector. By analysing what companies are publicly committing to in terms of their openness, policies and procedures, we seek to drive reform in the sector, reducing corruption and its impact. The DCI will assess 145 of the world’s leading defence companies across 39 countries. The Index was first published in 2012 with a second edition in 2015, and the latest edition is set to be published in 2019.

The upcoming index will apply a revised methodology and will include some key differences from previous editions. The draft Questionnaire and Model Answer document can be found here.

The 2015 DCI can be found here.

How will the 2019 Index be different?

After a comprehensive review, the new DCI assessment has evolved and should be read alongside our recent report ‘Out of the Shadows: Promoting Openness and Accountability in the Global Defence Industry’ – which provides greater insight into the theory behind our methodology. Based on consultations with anti-corruption and defence experts, TI DS have identified ten key areas where higher anti-corruption standards and improved disclosure can reduce the opportunity for corruption.

In one the most significant changes to the methodology, TI DS will this year base the research only on what companies choose to make publicly available. The decision to exclude internal information from the evaluation reflects our increased focus on transparency, public disclosure of information, incident response and the practical implementation of anti-bribery and corruption programmes.

How have companies been selected?

Companies for the 2019 DCI have been selected on the basis that:

- The company features in the 2016 edition of SIPRI’s Top 100 Arms-Producing and Military Services companies.

- The company features in the 2016 edition of Defence Industry Weekly’s Top 100 defence companies.

- The company is the largest national defence company headquartered in a country exporting at least £10 million, as identified by SIPRI.

To see the list of companies selected for assessment in 2019, click here.

How will data on companies be collected?

Our assessment of a company’s individual anti-bribery and corruption record is based entirely on publicly available information. In particular, we will review the company’s website, including any available reports, for evidence of robust anti-corruption systems, as well as any functioning hyperlinks to other relevant online materials. In reviewing your company’s materials, we will assess the completeness and accessibility of the information, in particular:

- The amount of information a company publishes about its internal anti-corruption programmes, incident response systems and interactions with third parties;

- Evidence that these systems are used by employees and made available to all employees;

- Evidence that the company monitors and reviews its anti-bribery and corruption processes.

Researchers from TI DS will conduct assessments of each company’s public information starting in May 2019, giving companies an opportunity to make any alterations to their publicly available information before the research process begins. The initial results will be shared with your company, after which you will have the opportunity to review the initial findings and suggest any corrections. The final assessments will be published on our website.

Where can I find the assessment criteria?

A draft version of the 2019 Questionnaire and Model Answer document is available here. Companies, governments, and civil society alike were invited to provide feedback on the methodology. To view an anonymised version of this feedback, click here.

We are currently reviewing this feedback and aim to publish a final version of the Question and Model Answer document by early February 2019.

Our recent report ‘Out of the Shadows: Promoting Openness and Accountability in the Global Defence Industry’ provides greater insight into the theory behind the changes to the 2019 methodology.

What is the timeline for the Index?

The draft questions and model answers for the 2019 assessments are now available at staging.clearhonestdesign.com/tids/dci.

We are currently reviewing the feedback received from companies, industry bodies and subject-matter experts and we will aim to publish a final version of the Question and Model Answer document early February 2019. Research will begin in May 2019 once companies have had some time to make improvements, should they wish to.

What do companies have to do next?

We are currently reviewing the feedback received from companies, industry bodies and subject-matter experts and we will aim to publish a final version of the Question and Model Answer document early February 2019. Research will begin in May 2019 once companies have had some time to make improvements, should they wish to.

Will we have an opportunity to give feedback on the methodology before the assessments start?

Yes – companies, industry groups and experts were able to provide feedback during a dedicated consultation period in November 2018. A document containing the entirety of this feedback in the form that it was submitted, with company names anonymised, is now available here.

Feedback is welcome from all users of the index including governments, civil society, journalists and companies.