Category: Responsible Defence Governance

Responding to reports of new security aid for Ukraine, Josie Stewart, Director of Transparency International Defence and Security, said:

Fresh security assistance for Ukraine is welcome, but history has taught us that aid packages of the size being pledged in recent weeks carry significant risk.

So far there is limited information about the defence companies delivering assistance to Ukraine, what influence they carry, and what measures they are taking to reduce corruption.

There is also always a risk that arms will end up in the wrong hands as the war continues.

Civilian oversight of military assistance is integral to robust defence governance and the strengthening of institutional resilience that is necessary to manage these risks.

This should be a shared responsibility between donor countries and Ukraine.

Responding to the United Nations Security Council all-day debate on the Rule of Law Among Nations, Josie Stewart, Director of Transparency International Defence and Security, said:

United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres last week reflected on the “strong and mutually reinforcing relationship between the rule of law, accountability and human rights”, describing how “ending impunity is fundamental”.

Our Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) facilitates such accountability by shining a light on the level of resilience to corruption — and independence of institutions — in countries as diverse as Israel and Mali.

Drawing on evidence contained within the GDI reveals critical steps governments can take to prevent the spectre of a “new rule of lawlessness” — a danger raised by Guterres at the Special Council session on January 12 .

press@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

Out of hours – Weekends; Weekdays (UK 17.30-21.30): +44 (0)79 6456 0340

Responding to claims that Russian mercenaries have been contracted in Burkina Faso, Josie Stewart, Director of Transparency International Defence and Security, said:

“Outsourcing national security to unregulated groups risks compounding conflict and corruption threats, rather than safeguarding civilian rights and resources. The people of Burkina Faso and the wider region are entitled to expect any roles being played by private actors to be transparent and accountable at all times.”

press@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

Out of hours – Weekends; Weekdays (UK 17.30-21.30): +44 (0)79 6456 0340

In response to reports Sweden plans to bring forward a commitment to spending two per cent of its GDP on defence, Josie Stewart, Director of Transparency International Defence and Security, said:

“As NATO countries increase their defence spending in response to the war in Ukraine, Transparency International is calling for equal commitment to strengthening oversight of defence procurement. While Transparency International’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) found corruption risk in Sweden’s defence sector to be only moderate, oversight of defence procurement remains limited and issues around industry influence remain unresolved. As Sweden prepares to join the NATO, these vulnerabilities must be addressed in order to build democratic resilience and safeguard both resources and lives.”

press@transparency.org.uk

+ 44 (0)20 3096 7695

Out of hours – Weekends; Weekdays (UK 17.30-21.30): +44 (0)79 6456 0340

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence and Security, describes some of the dangers documented in our latest research paper.

Unaccountable private military and security companies continue to pursue partnerships that in recent years have led indirectly to the assassination of presidents and journalists, land grabs in conflict zones, and even suspected war crimes.

From Haiti to Saudi Arabia to Nigeria, US-based organisations – the firms that dominate the market – have found themselves associated with a string of tragedies, all while their sector has grown ever-more lucrative.

Transparency International Defence and Security’s latest research – ‘Hidden Costs: US private military and security companies and the risks of corruption and conflict – catalogues the harm playing out internationally as countries increasingly seek to outsource national security concerns to soldiers of fortune.

Hidden costs from the trade in national security

While the US and other governments have left the national security industry to grow and operate without proper regulation, the risks of conflict being exploited for monetary gain are growing all the time.

Hidden Costs documents how the former CEO of one major US private military and security company was convicted – following a guilty plea – of bribing Nigerian officials for a US$6bn land grab in the long-plundered Niger Delta.

Our research also highlights that the Saudi operatives responsible for Jamal Khashoggi’s savage murder received combat training from the US security company Tier One Group.

Arguably most damning are the accounts from Haiti, where the country’s president was killed last year by a squad of mercenaries thought to have been trained in the US and Colombia.

Pressing priority

Many governments around the world argue that critical security capability gaps are being filled quickly and with relatively minimal costs through the growing practise of outsourcing.

Spurred on by the US government’s normalisation of the trade, US firms are growing both their services and the number of fragile countries in which they operate.

The private military and security sector has swelled to be worth US$224 billion. That figure is expected to double by 2030.

The value of US services exported is predicted to grow to more than $80 billion in the near future, but the industry and the challenge faced is global.

The risks of corruption and conflict in the pursuit of profits are plain.

These risks are as old as time. But their modern manifestations in warzones must not be left to spill over. The 20-year war in Afghanistan cultivated dynamics that threaten further damage, more than a decade after governments first expressed their concerns.

Required response

International rules and robust regulation are urgently needed. We need measures that ensure mandatory reporting of private military and security company activities. The Montreux Document lacks teeth, operating as it does as guidance that is not legally binding. Code of conduct standards must also become mandatory for accreditation, rather than purely voluntary.

Most private military and security firms are registered in the US. So Transparency International Defence and Security is also calling on Congress to take a leading role in pushing through meaningful reforms under its jurisdiction. There is an opportunity arriving in September, when draft legislation faces review.

Policymakers have long been aware of the corruption risks and the related threats to peace and prosperity posed by this sector. The time for action is well overdue. No more Hidden Costs.

By Ara Marcen Naval, Head of Advocacy at Transparency International Defence & Security

Last week the US President issued a government memorandum making corruption a core national security concern.

Transparency International’s new research reveals there is good cause for concern. The 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) shows that nearly two-thirds of countries – 62 per cent – face a high to critical risk of corruption in their defence and security sectors.

Countries that score poorly in the GDI have weak or non-existent safeguards against defence sector corruption. They are more likely to experience conflict, instability, and human rights abuses. Sudan, which has just undergone a military coup, came bottom of the Index with a score of 5/100 while New Zealand came top with a score of 85/100.

The GDI findings should ring alarm bells in governments around the world; particularly as global military spending has increased to some $2 trillion annually, fuelling the scale and opportunity for abuse.

Corruption in a nation’s defence institutions weakens security forces and threatens wider peace and stability. It eats away at public trust in the state and the rule of law, giving vital oxygen to non-state and extremist armed groups. It leaves governments unable to properly protect their citizens – their primary function. We have seen examples time and time again. Think of Iraq, when in 2014 50,000 ‘ghost soldiers’ (troops that exist only on paper) were found on the books. Their salaries were either stolen by senior officers or split between soldiers and high-ranking officers. The phenomenon has a human and financial cost leaving forces depleted, unprepared to face real threats and unable to fulfil their mandate to protect citizens and provide national security.

The GDI provides defence institutions across 86 nations with a comprehensive assessment of their corruption risk and a platform to identify the safeguards needed to prevent corruption. It does not measure corruption itself. It is not concerned with calculating stolen government funds, identifying corrupt figures, nor even estimating how corrupt the public thinks their defence forces are.

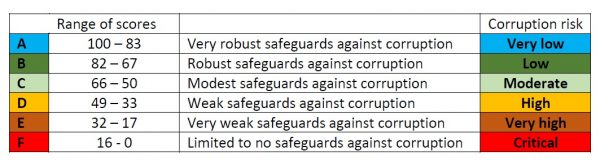

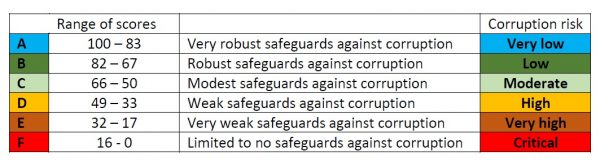

Rather, the GDI offers a roadmap for better governance of the defence sector. It maps out gaps in policies and practices that can prevent corruption and provides standards that countries can follow to strengthen their systems, across five main risk areas: policymaking and political affairs, finances, personnel management, military operations, and procurement. It assigns a score out of 100 and ranks countries from A (very robust safeguards) to F (limited to no safeguards against corruption).

Military operations

The GDI results are particularly poor when it comes to military deployments for internal security operations and peacekeeping missions overseas. Almost every country assessed performs badly in terms of anti-corruption safeguards in this area. That includes nations most actively engaged in international missions. Bangladesh scores 0/100 operationally yet is the top contributor of uniformed troops to UN peacekeeping missions.

Countries facing internal threats fare no better when it comes to military operations. A lack of anti-corruption safeguards means troops may be more likely to contribute to exacerbating conflict rather than bringing about peace.

These findings leave little doubt that governments are overlooking the corrosive impact of defence and security corruption despite its clear threat to peace, stability and human life.

Arms trade

The GDI also reveals significant corruption risks among the world’s major arms suppliers and recipients.

Eighty-six percent of global arms exports between 2016-2020 were from countries with a moderate to very high risk of corruption. For major arms suppliers, the GDI exposes poor parliamentary scrutiny, transparency and oversight in export and procurement processes. The top five exporters accounted for 76% of the global total.

Meanwhile, just under half – 49% – of global arms imports are to countries with a high to critical risk of defence corruption. These countries lack the policies and systems to independently oversee these deals or how these weapons will be used. Nor do they provide meaningful data on how they choose which companies to buy from or whether any third parties are involved. This lack of transparency leaves the door wide open to bribery, theft of public money and to weapons finding their way into the hands of criminal gangs or insurgent groups.

Overall, the GDI paints a dismal picture of a defence sector that continues to operate in secrecy, with inadequate policies and procedures to mitigate high corruption risks. This lack of transparency and accountability sets the scene for government activity that has devastating consequences for civilians and global security.

If governments are serious about building national and international security and stability, they must embed transparency and anti-corruption at the core of defence institutions. Getting this right is vital to averting future conflict, failed interventions and the devastating human cost that comes with them. To see the GDI results in detail go to https://ti-defence.org/gdi

November 16, 2021 – The 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) released today by Transparency International Defence & Security reveals nearly two-thirds of countries face a high to critical risk of corruption in their defence and security sectors.

Countries that score poorly in the GDI have weak or non-existent safeguards against defence sector corruption and are more likely to experience conflict, instability, and human rights abuses.

The results come as global military spending has increased to some $2 trillion annually, fuelling the scale and opportunity for corruption.

The GDI assesses and scores 86 countries across five risk areas: financial, operational, personnel, political, and procurement, before assigning an overall score. It uses the following scale:

Global highlights

- 62% of countries receive an overall score of 49/100 or lower, indicating a high to critical risk of defence sector corruption across all world regions.

- New Zealand tops the Index with a score of 85/100.

- Sudan, which just last month saw the military seize power in a violent coup, performs the worst, with an overall score of just 5/100.

- The average score for G20 countries is 49/100.

- Almost every country scores poorly in terms of its safeguards against corruption in military operations. The average score in this area is just 16/100 because most countries lack anti-corruption as a core pillar of their mission planning.

- Among those that scored particularly poorly in this area are key countries contributing to or leading major international interventions such as Bangladesh (0/100).

- 49% of global arms imports are sold to counties facing a high to critical risk of defence corruption.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence and Security Programme, said:

“These results show that most defence and security sectors around the world lack essential safeguards against corruption. Defence sector corruption undermines defence forces, weakening their ability to provide security to citizens, secure national borders and bring about peace. In the worst cases defence sector corruption has the potential to exacerbate conflict rather than to respond to it effectively.

“We urge all governments featured in this Index to act on these findings. They must strengthen their safeguards against corruption and remove the veil of secrecy that so often prevents meaningful oversight of the defence sector. It’s critical that they embed anti-corruption at the core of all military operations to stop corruption and its devastating impact on civilians around the world.”

Implications for military operations

Almost every country performs badly in the military operations risk area. The GDI assesses the strength of anti-corruption safeguards in military deployments, whether that be deploying troops for internal security purposes or sending them on a peacekeeping mission overseas.

Only New Zealand has a low risk of corruption in its military deployments (operations score of 71/100), while a handful of countries perform moderately well in this area, including the UK (operations score of 53) and Norway (50).

Eighty-one countries face a high to critical risk in their military operations. This poses serious questions for countries facing internal threats, where a lack of anti-corruption safeguards in operations means troops are far more likely to contribute to conflict than quell it.

The lack of corruption safeguards in military operations should also be alarming to governments involved in international interventions through regional and international organisations. For example, Bangladesh (operations score of 0/100) is the top contributor of uniformed troops to UN peacekeeping missions.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence and Security Programme, said:

“The lack of safeguards against corruption in military operations by many countries most actively involved in international interventions is particularly worrying. Time and time again international forces have failed to take the corrosive impact of defence and security corruption seriously despite the clear threat it poses to peace and stability. Getting this right is vital to averting future failed interventions and the devastating human cost that comes with them.”

Corruption in the arms trade

The GDI shows that 86% of global arms exports between 2016-2020 originate from countries at a moderate to very high risk of corruption in their defence sectors.

Meanwhile, 49% of global arms imports are to counties facing a high to critical risk of defence corruption.

These countries do not allow lawmakers, auditors or civil society to scrutinise arms deals, nor do they provide meaningful data on how they choose which companies to buy from or whether any third parties are involved.

This lack of transparency leaves the door wide open to bribery, public money being wasted and weapons finding their way into the hands of criminal gangs or insurgent groups.

Given the devastating impact on human life and security that corruption continues to have through the licit and illicit global arms trade, it is vital that both exporting and importing governments have strong anti-corruption measures and transparency.

Notes to editors:

About Transparency International

Through chapters in more than 100 countries, Transparency International has been leading the fight against corruption for the last 27 years.

The GDI is produced by Transparency International’s Defence and Security Programme, based in London, UK.

About the Government Defence Integrity Index

The GDI is the only global assessment of the governance of and corruption risks in defence sectors.

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI). The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. This means overall country scores from this 2020 version cannot be accurately compared with country scores from previous iterations of the Index.

For more information, visit www.ti-defence.org/gdi/about

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340 (out of hours)

Transparency International Defence & Security will release the full results of its Government Defence Integrity Index on Tuesday, November 16 at 00.01 CET.

The Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) is the only global assessment of corruption risks in the defence and security sector. It provides a snapshot of the strength of anti-corruption safeguards in 86 countries.

More on the GDI: https://ti-defence.org/gdi/about/

The GDI highlights a worrying lack of safeguards against corruption in defence and security sectors worldwide. It also shows countries contributing to or leading major international interventions lack key anti-corruption measures in their overseas operations.

Full results and scores for countries will be published here at 00.01 CET on Tuesday, November 16: https://ti-defence.org/gdi/map/

To request interviews or press materials under embargo until publication, please email the Transparency International UK press office press@transparency.org.uk

Our research shows Freedom of Information regimes in countries across the world are not good enough at protecting the public’s right to know

By Ara Marcen and Najla Dowson-Zeidan

The ‘right to know’ for citizens to learn what public institutions are doing on their behalf is a crucial component of human rights law, and vital to combat corruption by providing transparency and accountability. But as with all rights, there is often a big difference between being entitled to them and being able to realise them. With the right of access to information, nowhere is this gulf more apparent than in the defence and security sector.

Militaries, security institutions and ministries of defence are notoriously opaque. Despite robust international (and some national) anti-corruption and freedom of information legislation that governs public sectors, the defence sector is frequently given a green light to remain secretive and evade accountability by utilising the ‘national security’ exemptions so often contained in this legislation. The result is that secrecy is often the norm and transparency the exception.

This approach to transparency in defence needs to change. The secretive nature of defence, and a lack of transparency and access to information, impairs civilian control of the security sector, hampers oversight bodies and increases corruption risks at all levels. It allows corruption to occur unexposed, unaddressed, and in the shadows.

Transparency should be the norm and secrecy the exception. While some information in the defence sector may need to remain classified for legitimate national security reasons, this should be a well-founded exception – not a rule. Maintaining high levels of secrecy limits scrutiny and allows the vicious circle of secrecy, opportunity for corrupt acts and self-enrichment to flourish.

This International Right to Know Day, we call on all governments and public authorities to limit the opacity around security to only the most sensitive information – where the likelihood of harm as a result of its disclosure clearly outweighs the harm to the public interest in withholding it – so national security is not a pretext for limiting citizens’ right to information. Defence and security sectors should not be treated as exceptional when it comes to the public’s right to know how their money is being spent and how key policy decisions are being made.

Initial findings of our global Government Defence Integrity Index, a vast pool of data that assesses how government defence institutions protect themselves against the risk of corruption, show that in most countries there is a long way to go to make mechanisms for accessing information from the defence sector effective. Of the 86 countries assessed, almost half were assessed as at a high to critical risk of corruption in relation to their access to information regimes, meaning that the legal frameworks for access to information, implementation guidelines, and effectiveness of practice at the institutional level are currently not good enough at upholding citizens’ right to access information.

Weaknesses in legal frameworks regulating access to information in defence expose countries to high levels of corruption risk as they reduce transparency and hamper effective oversight of the sector. However, the implementation of these frameworks in practice presents even more significant risks. Poor implementation of Access to Information regulations in defence makes information extremely difficult to obtain and undermines the effectiveness of legislation.

The GDI data shows a significant implementation gap; even where legal frameworks are in place, most countries score less well in terms of actually putting this into practice The vast majority of countries fall well short of the good practice standard for implementation, whereby ‘the public is able to access information regularly, within a reasonable timeline, and in detail’. Most were assessed as having at least some shortcomings in facilitating access to defence-related information to the public (for example, delays in access or key information missing), and in more than one in three of the countries assessed the public is rarely able to access information from the defence sector, if at all. While corruption in every sector wastes resources and undermines trust between the state and its citizens, corruption in the defence and security sector, among institutions tasked with keeping peace and security, has a particularly detrimental impact. In fragile and conflict states, corruption – both a cause and a consequence of conflict – frequently permeates all areas of public life.

And the costs of this are high – both financially (with annual global military expenditure estimated to be almost $2 trillion[1]) and in terms of human security. Corruption damages populations’ conception of the legitimacy of central authorities, threatens the social contract, and ultimately the rule of law and attainment of human rights.

The right to information and transparency are key pillars for good governance and accountability and are crucial tools in the fight against corruption. They enable external oversight of government – and the military – by legislators, civil society and the media, increasing accountability of political decision-making and institutional practice. They enable informed participation of the public and civil society in public debates and development of policy and law. And they bring corruption risks – and actual incidents of corruption – to light, facilitating the push for accountability and reform.

Recommendations:

We’re calling on states to renew their commitment to the right to information. They need to ensure that their national legal frameworks include laws that enable the public to exercise the right of access to information across all sectors. Rules for classification and declassification must be rigorous and publicly available, with clearly defined grounds for classifying information, established classification periods. And there should be the possibility of appeal for those who wish to access information withheld in Freedom of Information proceedings.

Defence institutions should have in place rigorous and publicly available rules for withholding information, with clearly defined procedures and grounds for classifying information, established classification periods, and a possibility of appeal for those who wish to access information withheld in Freedom of Information proceedings. They should be accompanied by clear criteria and process for public interest and harm tests that can help balance genuine needs for secrecy with overall public interest. Adopting and endorsing the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (the Tshwane Principles) would be a good step towards having the right access to information regime in place.

To make sure that secrecy does not trump the right to know – and to strengthen the ability of defence institutions to protect themselves against the risk of corruption – governments should consider these key principles:

- Freedom of information is a right. Any limitations of this should be the exception, not the rule.

- Transparency is a key tool against corruption. Enabling public scrutiny, rather than undermining a public institution, can lead to better use of resources and reduce risk of corruption.

- The interest of preventing, investigating, or exposing corruption should be considered as an overriding public interest in public interest and harm tests, as corruption is not only a waste of public resources, but also seriously undermines the national security efforts of a country.

For more on Access to Information in the defence sector, see our factsheet.

[1] https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2021/world-military-spending-rises-almost-2-trillion-2020

May 6, 2021 – Close links between the defence industry and governments in Europe are jeopardising the integrity and accountability of national security decisions, according to a new report by Transparency International – Defence and Security.

Defence Industry Influence on Policy Agendas: Findings from Germany and Italy explores how defence companies can influence policy through political donations, privileged meetings with officials, funding of policy-focused think tanks and the ‘revolving door’ between the public and private sector.

These ‘pathways’ can be utilised by any business sector, but when combined with the huge financial resources of the arms industry and the veil of secrecy under which much of the sector operates, they can pose a significant challenge to the integrity and accountability of decision-making processes – with potentially far-reaching consequences.

This new study calls on governments to better understand the weaknesses in their systems that can expose them to undue influence from the defence industry, and to address them through stronger regulations, more effective oversight and increased transparency.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International – Defence and Security, said:

“When individuals, groups or corporations wield disproportionate or unaccountable influence, decisions around strategy and expenditure can be made to benefit private interests rather than the public good. In defence, this can lead to ill-equipped armed forces, the circumvention of arms export controls, and contracts that line the pockets of defence companies at the public’s expense.

“The defence and security sectors are a breeding ground for hidden and informal influence. Huge budgets and close political ties, combined with high levels of secrecy typical of issues deemed to be of national security, means these sectors are particularly vulnerable. Despite the serious risk factors, government oversight systems and regulations tend to be woefully inadequate, allowing undue influence to flourish, with a lot to gain for those with commercial interests.”

Transparency International – Defence and Security calls on states to implement solutions to ensure that their defence institutions are working for the people and not for private gain.

Measures such as establishing mandatory registers of lobbyists, introducing a legislative footprint to facilitate monitoring of policy decisions, strengthening conflict of interest regulations and their enforcement, and ensuring a level of transparency that allows for effective oversight, will be important steps towards curbing the undue influence of industry over financial and policy decisions which impact on the security of the population.

Notes to editors:

Defence Industry Influence on Policy Agendas: Findings from Germany and Italy is based on two previous reports which take an in-depth look at country case studies. The two countries present different concerns:

- In Italy, the government lacks a comprehensive and regularly updated defence strategy, and thus tends to work in an ad hoc fashion rather than systematically. A key weakness is a lack of long-term financial planning for defence programmes and by extension, oversight of the processes of budgeting and procurement.

- In Germany, despite robust systems of defence strategy formation and procurement, significant gaps in capabilities have led to an overreliance on external technical experts, opening the door to private sector influence over key strategic decisions.

The German report can be found here and the Italian report here.

The information, analysis and recommendations presented in the case studies were based on extensive document review and more than 50, mainly anonymous, interviews.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340 (out of hours)

New report warns close relationships and weak regulations leave door open to undue influence

28 April, 2021 – A close relationship between the defence industry and the Italian government jeopardises the integrity and accountability of the political decision-making process, according to new research by Transparency International – Defence and Security.

Released today, Defence Industry Influence in Italy: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the Italian Policy Agenda details how defence companies can use their access to policymakers to exert considerable influence over defence and security decision-making in Italy.

The report, prepared by Transparency International – Defence and Security with the support of the Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (CILD) and Osservatorio Mil€x sulle spese militari, invites the Italian government to understand better the weaknesses of its system such as to expose the decision-making process to undue influence by the defence industry, as well as to address them through more stringent regulations, more effective control and greater transparency.

In particular, Transparency International, Osservatorio Mil€x and CILD call on the Italian government to:

- Establish a process to publish and review a regular, clear and comprehensive national defence strategy with meaningful participation of different stakeholders including civil society.

- Introduce a new law to regulate lobbying and implement a mandatory stakeholder public register, with clear definitions and a public agenda of meetings between stakeholders and authorities, to allow full scrutiny.

- Widen the scope and applicability of ‘revolving door’ regulations to prevent conflicts of interest and reduce opportunities for undue influence

- Increase transparency in the export licensing process to allow for full and meaningful oversight.

Notes to editors:

- The full press release, in Italian, is available here.

- The report “Defence Industry Influence in Italy: Analysing Defence Industry Influence on the Italian Policy Agenda” was prepared by Transparency International – Defence & Security with the support of Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (CILD) and Osservatorio Mil€x sulle spese militari.

- The report examines the structures, processes and legal regulations designed to ensure transparency and control based on 20 expert interviews. The report is part of an overarching study of the influence of the defence industry on politics in several European countries.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

February 25, 2021 – Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts in West Africa are being undermined by a failure to address underlying corruption and a lack of accountability in the region’s security sectors, according to new research by Transparency International.

The Missing Element finds that strengthening accountability and governance of groups including the armed forces, law enforcement and intelligence services – not just providing training and new equipment – is a crucial but often neglected component to successful security sector reform (SSR).

By analysing examples from across West Africa, the report details how the high threat of corruption has undermined the rule of law, fuelled instability, and ultimately resulted in SSR efforts falling short of their objectives.

The report serves as a framework for policymakers to assess how corruption is fuelling conflict, then embed anti-corruption measures to reform the security sector into one which is more effective at maintaining peace and more accountable to the population it serves.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts across West Africa have focussed largely on providing training and equipment but rarely resulted in major change. This report details how a focus on anti-corruption and strengthening accountability has been the missing element. Only by recognising and understanding the impact of corruption in the defence and security sector and taking steps to combat it can these programmes hope to transform the sector into one which is both efficient and accountable.”

The Missing Element analyses security sector reform and governance in five countries that our research has previously flagged as being at a high risk of defence sector corruption: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria.

It concludes these interventions fell short because the focus was on providing practical support such as training programmes and new weapons and equipment (with between 80-90% of funding for SSR initiatives typically spent on these) rather than addressing underlying corruption.

The report assesses the main corruption risks in West Africa which are undermining SSR efforts, including:

Financial management

Limited or ineffective supervision over how defence budgets are spent present a huge corruption risk, but reforms to improve transparency in this area have often been neglected as part of SSR programmes.

National defence strategies in Niger and Nigeria are so shrouded in secrecy that it is impossible to determine whether defence purchases are legitimate attempts to meet strategic needs or individuals embezzling public funds. In Mali, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire, a lack of formal processes for controlling spending has resulted in numerous examples of unplanned and opportunistic purchases.

Defence sector oversight

Effective oversight and scrutiny of the defence sector by parliamentarians is essential to increase accountability and reduce opportunities for corruption, but despite being a key pillar of SSR, parliamentary oversight remains poor in West Africa.

In Ghana, only a handful of the 18 members of the Parliament Select Committee on Defence and Interior have the relevant technical expertise to perform their responsibilities. In Mali, the parliamentary body charged with scrutinising the defence sector was chaired by the president’s son until mid-2020. In Niger, the National Audit Office, which is responsible for auditing the defence sector’s spending, published its audit for 2014 in 2017.

Recommendations:

- SSR policymakers at institutional level, such as United Nations (UN), African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), to publicly acknowledge the nexus between corruption and conflict, and adapt SSR policy frameworks accordingly.

- SSR practitioners operating in West Africa to undertake corruption-responsive SSR assessments to better inform the design of national SSR strategies and in all phases of their implementation.

- SSR practitioners to build on anti-corruption expertise to ensure that corruption is addressed as an underlying cause of conflict.

Notes to editors:

Security sector refers to the institutions and personnel responsible for the management, provision and oversight of security in a country. Broadly, the security sector includes defence, law enforcement, corrections, intelligence services and institutions responsible for border management, customs and civil emergencies.

Security sector reform (SSR) is a process of assessment, review and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation led by national authorities that has as its goal the enhancement of effective and accountable security for the state and its peoples without discrimination and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law.

The five countries analysed in this report (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria) were previously assessed in Transparency International Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index.

About Transparency International Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.