Country: Niger

Access to information is a cornerstone of healthy, accountable and transparent societies and essential for democracy.

By improving the public’s ability to obtain and use government-held information, citizens are empowered to participate fully in democratic processes, make informed decisions, and hold their leaders accountable.

Access to information is vital in all public sectors, but particularly so in defence and security where high levels of secrecy combined with substantial public budgets greatly increase the risk of corruption. Transparency and access to information in this sector provides a crucial bulwark against the misuse of funds, ensures accountability, and maintains public trust.

Ahead of Access to Information Day 2024, we’re excited to share details of our upcoming report which provides a comprehensive overview of the state of defence transparency and access to information worldwide.

Our report aims to strengthen accountability by enhancing access to defence information, in line with our broader goal to ensure informed and active citizens drive integrity in defence and security.

Utilising our Government Defence Integrity (GDI) 2020 database, which assesses institutional integrity and corruption risks, the report offers a detailed assessment of global defence transparency and access to information, with a focus on defence finances including budgeting information and spending practices. This is particularly urgent in an era of increasing military spending. The latest defence spending data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) shows world military expenditure rose for the ninth consecutive year to an all-time high of $2.443 trillion in 2023. This represents an increase of 6.8 per cent in real terms from 2022, which is the steepest year-on-year increase since 2009.

Additionally, the report also includes a review of global standards for transparency that apply to the defence sector. This is coupled with insightful case studies from Niger, Tunisia, Malaysia, Armenia and Guatemala and a review of good practices. The report concludes with recommendations to enhance access to information in particular contexts.

We look forward to sharing the full report and the accompanying case studies shortly. Updates on the launch date will be provided via our X/Twitter and LinkedIn accounts.

A year on from the coup d’etat in Niger, Denitsa Zhelyazkova looks back at what has changed so far and what needs to happen to address corruption in the country’s defence sector.

Last month marked an important date for political leaders and human rights advocates all around the globe: one full year after the coup d’etat in Niger. On July 26, 2023, senior army officers from the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (Conseil National pour la Sauvegarde de la Patrie, or CNSP), led by General Abdourahamane Tchiani, seized power, suspended the constitution and detained country’s democratically elected leader, President Mohamed Bazoum. The junta claimed the reasons for the coup were the continuous deterioration of the security situation under Bazoum and poor economic management, among others. On August 20 that year, the coup leader proposed a three-year transition plan back to democratic rule, but concrete steps towards this have yet to materialise. Even though the 2023 mutiny was not a new phenomenon for the region, especially given the number of recent putsches in neighbouring Mali and Burkina Faso, this coup signifies a pivotal point in Nigerien politics.

Major changes since the coup

- Cutting ties with the West and regional actors: Niger is heading for a shift in strategic alliance and moving away from traditional Western security providers. Strengthening regional ties with Mali and Burkina Faso under a new mutual defence pact called the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) resulted in the new ‘Confederation of Sahel States’, emphasising both economic and military cooperation. They signed a treaty on the July 6 this year restating their sovereignty from France’s influence in the region, their departure from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), as well as their aim to create a new common currency. In addition to potentially having catastrophic economic and further humanitarian consequences, this step will likely complicate relations with neighbouring states and reshape international influence in the Sahel region.

- New anti-corruption body: General Tchiani has dissolved two of the country’s highest courts, the Court of Cassation and State Council, replacing them with a new anti-corruption Commission and a State Court. The commission’s main role will be recovering all illegally acquired and misappropriated public assets. Consisting of judges, army and police officers as well as representatives of civil society, the selection process of these members lacked transparency. Furthermore, it is not clear at this stage whether the anti-corruption regulations discussed under Bazoum will be implemented and whether the transitional commission and court can have an impact on that.

Damage

Turning away from democracy rarely leads to peace and stability.

In the immediate aftermath of the coup, violence and human rights abuses spiked, with Human Rights Watch reporting that CNSP supporters looted and set fire to the headquarters of Bazoum’s party, the Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS).

France, the EU, and the US condemned the coup and suspended development aid. UN humanitarian operations were also stopped. The African Union (AU) responded by suspending Niger, while ECOWAS closed its borders, demanded Bazoum’s release, and threatened military intervention and sanctions. Tensions escalated further as Mali and Burkina Faso warned that ECOWAS intervention would be considered a ‘declaration of war’ against them.

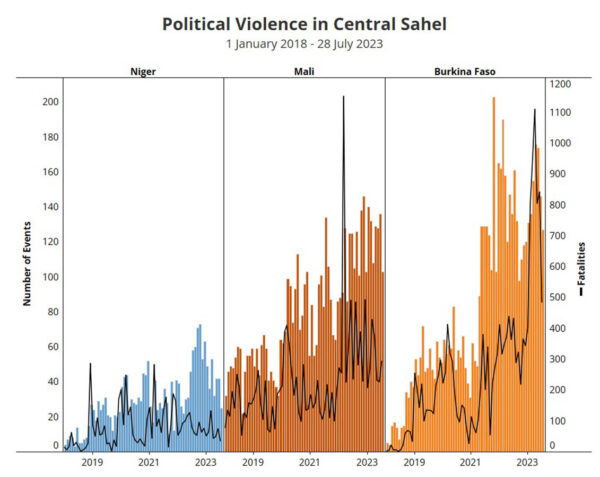

The putsch and its direct economic consequences are now threatening to worsen human suffering in the landlocked country that has been grappling with poverty, political instability and endemic corruption for decades. Being one of the poorest countries in world, Niger recently ranked 189 out of 193 territories in the critical HDI value from the UN’s Human Development Index, signalling a dire humanitarian crisis. Even though ECOWAS sanctions were lifted in February this year for humanitarian purposes, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported a surge in humanitarian need. An additional 600,000 people required humanitarian assistance in 2023, to an estimated total of some 4.3 million people, as extreme poverty is expected to reach 52%. Despite faring comparatively better against Burkina Faso and Mali in terms of fatalities, Niger is still suffering with violence and internal turmoil, with over 370,000 internally displaced people, primarily consisting of women and children.

ACLED graph using their own data on political violence, August 3, 2023.

The vicious cycle of conflict and corruption

Niger has been struggling with jihadist violence and security threats on several fronts, from IS Sahel and the al-Qaeda-affiliated JNIM in the west and south of the country, to bandits, organised crime networks in resource-rich Agadez as well as Tahoua, and even Boko Haram rebels around Diffa near the border with Nigeria. Despite these serious security challenges, historically weak governance of the defence sector has been eroding Niger’s capabilities to defend its own citizens. An embezzlement case in 2020 revealed how a notorious arms dealer exploited government contracts for nearly a decade to funnel hundreds of millions of dollars to purchase weapons from Russia. With more than $130 million lost to corruption in this case alone, it brought to light just how urgent reform of the security sector, with anti-corruption at the core, is.

Now that the country is ruled by a military government, increased levels of secrecy are expected to rise around defence planning and spending, as well as personnel recruitment and payments. The newly adopted Ordinance 2024-05 of February 23, 2024, is a huge step backwards in terms of good governance in the security sector, allowing for even more opaque practices in defence budget planning and management. The new decree dictates that public procurement and public accounting expenses related to the acquisition of equipment, materials, supplies, as well as the performance of works or services intended for the Defense and Security Forces (FDS) are exempt from regular oversight regulations. Moreover, defence expenses are exempt from taxes, duties and fees during the transition period. Unfortunately, opaque practices have become the norm when it comes to Niger’s defence governance.

The 2020 iteration of Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) found that Niger faces a very high level of corruption risk, which is consistent with other fragile and conflict-affected states in the region. The results showcase the country’s issue with building robust institutions despite increased military spending and advanced operational training by Western allies in the past years. Scoring in the bottom quarter of the GDI 2020, Niger received the lowest score of all West African countries assessed in the index, with secrecy and opaque procurement practices being the biggest concerns. According to the 2013 Decree on defence and security procurement, Niger’s defence acquisition plan is not subject to public disclosure and is classified as “top secret,” nor is the plan subject to legislative scrutiny by the Security and Defence Committee. Despite the egregious 2020 embezzlement case, findings from a 2022 audit on state spending estimate budget discrepancies of approximately $99 million. Greater public oversight of defence spending, not expanded exemptions from transparency for the military and security services, is vital to restoring public trust and to ensure much-needed funds are not lost to corruption. Considering the new cooperation agreements with global actors notorious for the high levels of corruption risk in their defence sectors – such as Russia and Turkey – it is crucial for Niger to prioritise transparency and accountability in its defence governance.

One key rationale the military provided for the taking power last year was the worsening security in the country. However, violence has persisted and escalated, calling into question the effectiveness of military operations. Oversight of military spending has also been curtailed. Corruption in the defence sector not only hinders military capabilities, but also erodes public trust in the very institutions established to protect citizens. If opaque practices persist, allowing greedy officials to benefit while citizens continue to suffer, this can bring even more instability. Following the steps of Mail and Burkina Faso could potentially drag Niger into a vicious cycle of coups, violence, loss of territory to rebels, and of course the fuel driving the cycle – widespread corruption in the security sector. The path to democracy inevitably starts with focusing efforts on building resilient institutions and addressing corruption as a top priority through an urgent (and long-overdue) security sector reform.

July 30, 2024 – Transparency International Defence & Security (TI-DS) expresses deep concern that the potential ‘disintegration’ of state cooperation in West Africa could exacerbate conflict in the already unstable region.

Following a summit of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) earlier this month, the bloc cautioned the formation of a breakway union, run by the military juntas in Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, would worsen insecurity and disrupt the work of a long-proposed regional force.

Research by TI-DS previously found that Mali, Niger, Ghana and Nigeria all face a very high risk of corruption in their defence and security sectors, while Burkina Faso is at a critical risk. Corruption in these sectors increases the risk of conflict and weakens the ability to manage and resolve unrest, compromising regional stability.

Sara Bandali, Director of International Engagement at Transparency International UK, said:

“We express deep concern over the recent warning from ECOWAS about the potential damage to the region’s security following the formation of a breakaway union by the military rulers of Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. In a region already marred by conflict and insecurity – much of which has been caused or exacerbated by corruption in the defence and security sectors – this move threatens to make the region and its people less safe.

“Cooperation, not competition, are key to addressing the corruption and insecurity issues the region faces. It’s clear that corruption in the defence and security sectors makes conflict more likely by fuelling the flames of grievance and unrest, while simultaneously making it harder to manage conflicts after they arise by weakening the effectiveness of military response.

“We urge regional leaders to prioritise unity and collective action for a secure future free from corruption and the conflict that both stems from, and is fuelled by it. We stand ready to support governments and civil society in the region in this vital endeavor.”

Notes to editors:

Mali, Niger, Ghana and Nigeria and Burkina Faso feature in Transparency International Defence & Security’s 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI).

The Index scores and ranks countries based on the strength of their safeguards against defence and security corruption.

Mali, Niger, Ghana and Nigeria all appear in band ‘E’, indicating a ‘very high’ risk of corruption. Burkina Faso is in band ‘F’, indicating a ‘critical’ risk.

L’impact corrosif de l’abus de pouvoir sur les perspectives de paix et de justice en Afrique de l’Ouest a été illustré lors de notre dernier événement organisé à Peace Con ’23. Les intervenants de la région ont déploré une “célébration” de la corruption dans des pays où des millions de dollars destinés à la lutte contre le terrorisme ont disparu, tandis que des soldats ont perdu la vie en raison d’un manque d’équipement. Nos responsables du plaidoyer Ara Marcen Naval et Najla Dowson-Zeidan font le point sur les idées et les recommandations formulées par leurs collègues du Sahel.

Le Cadre : un moment charnière où le monde se trouve à mi-parcours des objectifs de développement durable (ODD) et entame des discussions sur le nouvel agenda pour la paix des Nations Unies. Il s’agit d’un moment crucial pour faire la lumière sur la corruption en tant que catalyseur menaçant de conflit, entravant la paix et le développement durable.

Dans ce contexte, Transparency International Défense et Sécurité a réuni au début du mois un panel composé d’intervenants basés au Burkina Faso, au Niger et au Nigeria, foyers de conflits en Afrique de l’Ouest, à l’occasion d’un événement organisé par l’Alliance pour la paix dans le cadre de la conférence sur la paix 2023. Notre session était intitulée “S’attaquer à la corruption pour la paix : Les approches anti-corruption pour lutter contre la fragilité et l’insécurité”. L’objectif ? Souligner le rôle indispensable de la lutte contre la corruption dans la réalisation de la vision de paix, de justice et d’institutions fortes de l’ODD 16 et écouter la voix de celles et ceux qui ont consacré des années à la redevabilité de leurs secteurs de sécurité, à amplifier leur efficacité et à leur donner les moyens de faire face aux conflits et à l’insécurité et de protéger la vie des civils.

Le panel a appelé à ce que la lutte contre la corruption devienne une priorité absolue, comme le prévoit l’objectif de développement durable n° 16. Il est temps qu’un mouvement mondial œuvre à la redevabilité des gouvernements, ouvrant la voie vers un avenir où la corruption est démantelée, où la justice prévaut et où le développement durable prospère pour tous.

Témoignages de première ligne

Nous avons entendu des récits provenant de trois pays : Nigeria, Niger et Burkina Faso.

Nigeria – la corruption est célébrée

Bertha Eloho Ogbimi, représentant le Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC) au Nigeria, a illustré la manière dont la corruption effrontée a entravé les progrès dans la résolution de l’insécurité et de l’insurrection dans le pays au cours des dernières années. Le conflit a ravagé la nation, alimenté par la corruption qui siphonne les fonds, affaiblit les forces de sécurité et empêche une résolution efficace.

La corruption au Nigeria a rendu la population vulnérable et les voies de la paix non résolues. Bertha a brossé un tableau saisissant de la situation, en décrivant les différents domaines de risque mis en évidence dans l’évaluation de l’indice d’intégrité de la défense gouvernementale (GDI) du Nigeria. Des exemples ont été présentés, tels que le détournement d’argent des budgets publics, comme dans le cas de la saga du Dasukigate, où jusqu’à 2 millions de dollars auraient été détournés d’un budget consacré à des acquisitions d’armes.

Ce scandale a laissé les forces de sécurité et de défense en manque de ressources pour faire face aux multiples menaces, tandis que les rôles clés étaient attribués sur la base du népotisme plutôt que de l’aptitude.

Plus alarmant encore, Bertha a décrit comment des membres du personnel militaire ont eu recours à des ventes d’armes destinées à lutter contre l’insurrection pour compléter leurs revenus. Bertha a fait référence à des enquêtes qui “ont prouvé sans l’ombre d’un doute que l’une des principales raisons pour lesquelles cette insécurité n’est pas encore traitée de manière holistique est le fait que certaines personnes profitent financièrement des retombées de l’insécurité”.

La responsable de programme de la CISLAC a ensuite parlé des agences de sécurité qui ont pris le contrôle de petites entreprises appartenant à des citoyens, les soumettant à un chantage pour payer une protection financière sous la menace d’être accusées d’être impliquées dans des activités terroristes.

Elle a souligné l’impunité qui règne dans le secteur. Même les affaires de corruption qui, dans un premier temps, parviennent devant les tribunaux et attirent l’attention des médias s’essoufflent après un certain temps et semblent ne pas donner lieu à des poursuites. Bertha a dépeint une sombre réalité en déclarant : “Au Nigeria, la corruption est célébrée… les gens sont promus pour récompenser leur corruption. Il ne devrait pas en être ainsi et cela ne peut pas être la norme”.

CISLAC a milité sans relâche pour la lutte contre la corruption dans le secteur de la défense, en s’engageant activement auprès des institutions de défense nigérianes. Cependant, l’organisation a constaté des obstacles à un engagement plus large de la société civile sur ces questions, ce qui compromet la mission de démanteler l’impunité et d’assurer la redevabilité du secteur. Bertha a souligné le besoin urgent de renforcer la société civile, en encourageant sa participation informée. Il s’agit là d’un effort permanent poursuivi par la CISLAC en collaboration avec des partenaires dans l’ensemble du pays.

Niger – traduire des défis en recommandations

Shérif Issoufou Souley a représenté l’Association Nigérienne de Lutte Contre La Corruption (ANLC). Il a décrit l’inaccessibilité de la défense et de la sécurité du Niger aux yeux des communautés et de la société civile.

Opaques et donc non scrutés, il a décrit comment ces secteurs héritent de pratiques anciennes de secret et de répression établies à l’époque coloniale. Shérif a mis en lumière ” le manque de redevabilité, l’opacité et le manque de communication avec les civils de ce secteur “.

Ajouté au contrôle limité découlant du secret défense, cet environnement est devenu un terrain propice à la corruption et à la mauvaise gouvernance. Shérif a mis en évidence les domaines critiques où la corruption s’est infiltrée.

L’opacité due à l’utilisation abusive du secret défense est un obstacle même pour les organes de contrôle au sein des départements d’audit et législatifs, y compris la commission de la défense et de la sécurité du parlement. Un récent audit indépendant mandaté par le ministère nigérien de la défense a révélé que des dizaines de milliards de francs CFA (dizaines de millions de dollars américains) ont été attribués au budget des marchés publics du ministère de la défense, sans que l’on sache ce qu’il est advenu de cet argent, ce qui a des conséquences évidentes sur les ressources dont disposent les forces armées.

En réponse aux scandales de corruption alarmants dans le secteur, l’ANLC a mené un plaidoyer pour l’adoption de textes législatifs garantissant la transparence et la redevabilité à travers des mesures de lutte contre la corruption dans ce secteur. Cet avant-projet de loi est maintenant approprié par des parlementaires au Niger. ANLC a par ailleurs travaillé à la mobilisation de la société civile, en organisant des débats publics sur la sécurité et la corruption et en réunissant des comités de civils et d’acteurs de la sécurité. L’objectif était de “promouvoir la bonne gouvernance et de s’attaquer à la corruption… afin que l’armée et la société civile puissent travailler main dans la main pour résoudre ces problèmes”.

Le dialogue civilo-militaire établi par l’ANLC a débouché sur un forum national pour la paix et la sécurité, regroupant des acteurs de tous les secteurs et de toutes les régions du Niger. Les défis ont été traduits en recommandations qui ont été présentées au président de la République du Niger, Mohamed Bazoum. ANLC a expliqué que la méfiance entre les civils et les forces de sécurité dans les régions frontalières nuit à la sécurité. Les forces de sécurité doivent établir de meilleures relations avec les populations locales.

Burkina Faso – pris en otage par la corruption

Enfin, apportant une perspective claire du Burkina Faso, Sadou Sidibe, conseiller principal du DCAF en matière de réforme du secteur de la sécurité (RSS), a révélé l’impact périlleux de la corruption sur les efforts de RSS. “La corruption est le carburant de l’insécurité”, a-t-il dit, rappelant à tout le monde l’impact profond qu’elle a sur la sécurité humaine. “Aujourd’hui [au Burkina Faso], la corruption est devenue systématique… la sécurité et le développement sont pris en otage par ce problème.

Les jeunes officiers militaires qui ont mené le coup d’État de 2020 ont justifié leur prise de pouvoir en soulignant la corruption qui régnait dans le secteur de la défense, où une grande partie du budget alloué aux programmes d’acquisition avait été détournée par des fonctionnaires corrompus.

La justification de la junte pour le second coup d’État, en 2022, s’est également appuyée sur des allégations de corruption – cette fois-ci affirmant qu’une grande partie des dépenses destinées à la lutte contre le terrorisme avait été détournée par leurs prédécesseurs.

Par conséquent, la corruption est dorénavant au cœur du débat au Burkina Faso, et Sadou a décrit comment la corruption est devenue endémique à différents postes, que ce soit dans la chaîne de la commande publique, la gestion du budget et même dans certains cas avec les bailleurs de fonds.

Pour aborder ces questions, le DCAF en partenariat avec l’autorité supérieure de contrôle d’Etat et de lutte contre la corruption (ASCE-LC) a organisé des ateliers régionaux avec les principaux organes de contrôle du Mali, du Niger et du Burkina Faso, ainsi qu’avec la société civile, afin de discuter et de convenir des meilleures pratiques en matière de gestion des ressources dans la gouvernance du secteur de la défense.

Sadou a mis l’accent sur les domaines clés dans lesquels la réforme institutionnelle peut jouer un rôle dans l’élimination du potentiel de corruption : le renforcement de l’autonomie des fonctions d’audit et la réglementation du secret défense afin de permettre une veille et un contrôle externes.

Il y a eu des avancées positives ces dernières années, comme l’exemple de RENLAC, une coalition d’organisations de la société civile burkinabè de lutte anticorruption qui a réussi à engager un procès et à faire déférer un ministre de la Défense pour corruption en 2018. Mais M. Sadou a souligné l’importance pour le rôle important que doit jouer le système judiciaire en donnant suite aux affaires de corruption afin de montrer qu’il n’y a pas d’impunité. Alors que les budgets de défense dans la région ont explosé au cours des cinq dernières années, notre dernier intervenant a souligné l’importance de mécanismes de contrôle efficaces pour réduire la menace de la corruption dans le secteur.

En outre, pour garantir un développement pacifique et durable avec la sécurité humaine au cœur, il est primordial que la corruption reste au premier plan des conversations nationales, régionales et mondiales.

Comme l’a bien résumé Martijn Beerthuizen, président de notre panel et coordinateur politique au ministère des affaires étrangères des Pays-Bas, “la corruption remet en cause la confiance dans le secteur de la sécurité et s’attaquer à la corruption en tant que problème nous aidera à garantir des sociétés pacifiques”.

Le message retentissant du panel était clair : Nous devons aller de l’avant avec une détermination inébranlable, unis dans notre mission de démanteler l’emprise de la corruption, de faire respecter la justice et d’ouvrir la voie à des sociétés harmonieuses et sûres.

The corrosive impact of abuse of power on prospects for peace and justice in West Africa was illustrated at our latest event staged at Peace Con ‘23. Campaigners from the region lamented a “celebration” of corruption in countries where millions of dollars earmarked for fighting terror have gone missing, while soldiers have lost their lives amid a lack of equipment. Our Advocacy leads Ara Marcen Naval and Najla Dowson-Zeidan round-up insights and recommendations shared by colleagues in the Sahel.

The Setting: a pivotal moment in time, where the world stands at the midpoint of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and embarks on discussions about the UN’s New Agenda for Peace. It is a critical moment to shed light on corruption as catalyst for conflict, hindering peace and sustainable development.

Against this background, Transparency International Defence and Security convened a panel of speakers from West African conflict hotspots Burkina Faso, Niger and Nigeria earlier this month for an event at the Alliance for Peace’s 2023 Peace Con . Our session was entitled “Tackling Corruption for Peace: Anti-Corruption Approaches to Address Fragility and Insecurity”. The aim? To underscore the indispensable role of combatting corruption in achieving SDG 16’s vision of peace, justice and strong institutions and to hear the voice of those who have dedicated years to holding their security sectors accountable, so that they can effectively confront conflict, insecurity and safeguard civilian lives.

The panel demanded that fighting corruption becomes a top priority, as enshrined in SDG 16. It’s time for a global movement to hold governments accountable, paving the way for a future where corruption is dismantled, justice prevails, and sustainable development thrives for all.

Testimonies from the frontline

We heard stories from three countries: Nigeria, Niger and Burkina Faso.

Nigeria – corruption is celebrated

Bertha Eloho Ogbimi, representing the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC) in Nigeria, illustrated how brazen corruption has obstructed progress in resolving the country’s insecurity and insurgency in recent years. Conflict has ravaged the nation, fuelled by corruption that siphons funds, weakens security forces and hinders effective resolution.

Corruption in Nigeria has left the population vulnerable and routes to peace unresolved. Bertha painted a vivid picture, outlining various risk areas exposed in Nigeria’s Government Defence Integrity index (GDI) assessment. Examples were shared of money being drained from public budgets, as in the case of the Dasukigate saga, where up to $2 million was reportedly embezzled from an arms procurement budget. This scandal left the security and defence forces under-resourced to face down multiple threats, while key roles were awarded based on nepotism rather than suitability.

Even more alarming, Bertha described how military personnel resorted to supplementing their income through weapon sales meant to combat insurgency. Bertha referred to investigations that ‘have proven beyond doubt that one of the major reasons why this insecurity is yet to be holistically addressed is because of the fact that some persons are benefitting financially from proceeds of insecurity’.

CISLAC’s senior programme officer talked about security agencies taking over small businesses belonging to citizens, blackmailing them into paying protection money to prevent accusations of being engaged in terrorist activities.

She emphasised the impunity in the sector. Even cases of corruption that initially reach the courts and the attention of the media die down after a while and seem to not proceed. Bertha painted a grim reality, saying: “In Nigeria, corruption is celebrated … people are promoted to award corruption. This ought not to be so and cannot be the norm.”

CISLAC has relentlessly championed the fight against defence sector corruption, actively engaging with Nigerian defence institutions. However, they have seen barriers to wider civil society engagement in these issues, undermining the mission to dismantle impunity and ensure accountability of the sector. Bertha stressed the urgent need to empower civil society, fostering their informed participation. This is an ongoing endeavour pursued by CISLAC in collaboration with partners across the nation.

Niger – translating challenges into recommendations

Shérif Issoufou Souley represented the Association Nigérienne de Lutte Contre La Corruption (ANLC). He described the inaccessibility of Niger’s defence and security in the eyes of communities and civil society.

Hidden from view and therefore unscrutinised, he described a legacy of long-standing practices established during colonial times of secrecy and repression. Shérif shed light on “this sector’s unaccountability, opaqueness and lack of communication with civilians”.

Compounded by limited oversight stemming from defence secrecy, this environment has become a breeding ground for corruption and misgovernance. Shérif highlighted critical areas where corruption has seeped in.

Opacity driven by the abusive use of defence secrecy is an obstacle even to oversight bodies within audit and legislative departments, including parliament’s defence and security committee. A recent independent audit commissioned for Niger’s ministry of defence revealed that tens of billions of CFA Francs (tens of millions of US dollars) have been attributed in the MoD’s public procurement budget, but with no sign of what happened to the money, with clear implications for the resources available to the armed forces.

In response to alarming corruption scandals in the sector, ANLC has advocated for legislation for transparency and accountability in the sector, through anti-corruption measures. This draft law is now supported by a group of parliamentarians in Niger. ANLC has also been working on mobilising civil society, organising public debates on security and corruption and bringing together committees of civilians and security actors. The goal has been “to promote good governance and tackle corruption… so that military and civil society can work hand-in-hand to address these issues”.

The civil-military dialogue established by ANLC led to a national peace and security forum, grouping actors across sectors and geographies within Niger. Challenges were translated to recommendations which were presented to the President of the Republic of Niger, Mohamed Bazoum. Distrust between civilians and security forces in border regions undermines security, he was told. Security forces need to build better relations with local populations.

Burkina Faso – held hostage by corruption

Finally, bringing a vivid perspective from Burkina Faso, DCAF’s senior Security Sector Reform (SSR) advisor Sadou Sidibe revealed the perilous impact of corruption on SSR efforts. “Corruption is the fuel for insecurity”, he said, reminding everyone of the profound impact it has on human security. “[In Burkina Faso] today … corruption has become systematic… security and development are taken hostage by this problem.”

The young military officers who led the 2020 coup justified their seize of power by pointing to the corruption prevalent in the defence sector, where a lot of budget allocated for procurement programmes had been diverted by corrupt officials. The junta’s justification for the second coup, in 2022, also hinged on claims of corruption – this time that a lot of anti-terrorism expenses had been diverted by their predecessors.

Consequently, corruption is now centre-stage as an issue for debate in Burkina Faso, and Sadou described how corruption has become endemic in various positions, whether in the command chain, budget management and even in some cases with funders.

To address these issues, DCAF, in partnership with the the High Authority for State Audit and the Fight against Corruption (ASCE-LC), has organised regional workshops with the key oversight bodies in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso – together with civil society – to discuss and agree on best practice in resource management in defence sector governance.

Sadou pointed to key areas where institutional reform can play a role in rooting out the potential for corruption: strengthening the autonomy of audit functions and regulating defence secrecy to enable external oversight and scrutiny. There have been positive developments in recent years, such as the example of RENLAC, a Burkinabe coalition which managed to engage a case to prosecute the Minister of Defence for corruption in 2018,. But Sadou emphasised the important role of the justice system in following up corruption cases to show that there is no impunity. With defence budgets in the region soaring over the past five years, our closing speaker emphasised the importance of effective oversight mechanisms to reduce the threat of corruption in the sector.

Furthermore, to ensure peaceful, sustainable development with human security at its core, it is paramount that corruption remains at the forefront of national, regional, and global conversations.

As Martijn Beerthuizen, the Chair of our panel and Policy Coordinator at the Netherlands MFA, aptly summarised, “Corruption challenges trust in the security sector and tackling corruption as an issue will help us ensure peaceful societies.”

The resounding message from the panel was clear: we must forge ahead with unwavering determination, united in our mission to dismantle corruption’s grip, uphold justice, and pave the way for harmonious and secure societies.

A forum tracking progress towards the 2030 sustainable development agenda has been taking place in Niger this week. With matters of security preoccupying policymakers and the public across the region, the moment has come for commitments made by United Nations members to be translated into action.

The aim of the ninth Africa Regional Forum on Sustainable Development is to take stock of how far countries have progressed towards the implementation of five of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an ambitious set of development targets to be met by 2030.

However Goal 16, “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions”, is not part of the review, although the security challenges facing countries including Niger, Nigeria and Mali should serve to remind delegates of the urgent need to address corruption-related risks to defence and security.

Goal 16 includes commitments to fight corruption, increase transparency, tackle illicit financial flows and improve access to information to achieve peaceful societies. Without meaningful action to reduce corruption, little progress will be achieved in the five SDGs selected for discussion: Goals 6 (clean water and sanitation); 7 (affordable and clean energy); 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure); 11 (sustainable cities and communities); and 17 (partnerships for the Goals).

Corruption, organised crime, the use of illicit financial flows to fund terrorism and violent extremism and forced displacement of people threaten to reverse much development progress made in recent decades. Mali is a case in point. Impunity to corruption, terrorism, drug trafficking and other forms of transnational organised crime undermine stability and development.

In Nigeria, where high-profile elections have been fought in recent days, memories of the deadly End SARS protests continue to linger.

Elsewhere conflicts and instability add to natural disasters, causing untold human suffering. Our ability to prevent and resolve conflicts and build resilient, peaceful and inclusive societies has often been hampered by endemic and widespread corruption.

We must take action and do so by embracing a “whole-of-society approach,” fostering dialogue, cooperation, and partnerships between state and non-state actors to promote transparency, accountability, and effective oversight, in line with Goal 16 of the SDGs.

Failing to take action on SDG 16 following the forum would be a missed opportunity, especially when coordinated efforts and commitments are needed from states in and out of Africa, to address the complex problem of corruption and its threat to human lives.

Jacob Tetteh Ahuno, Projects Officer, Ghana Integrity Initiative; Mohamed Bennour, Transparency International Defence and Security Project Manager; Ara Marcen-Naval, Transparency International Defence and Security Head of Advocacy; Bertha Ogbimi, Programme Officer, CISLAC; Abdoulaye Sall, President of CRI 2002

Image: Lagos, Nigeria, during the End SARS protests of October, 2020.

Michael Ofori-Mensah, Head of Research at Transparency International Defence and Security, describes some of the dangers documented in our latest research paper.

Unaccountable private military and security companies continue to pursue partnerships that in recent years have led indirectly to the assassination of presidents and journalists, land grabs in conflict zones, and even suspected war crimes.

From Haiti to Saudi Arabia to Nigeria, US-based organisations – the firms that dominate the market – have found themselves associated with a string of tragedies, all while their sector has grown ever-more lucrative.

Transparency International Defence and Security’s latest research – ‘Hidden Costs: US private military and security companies and the risks of corruption and conflict – catalogues the harm playing out internationally as countries increasingly seek to outsource national security concerns to soldiers of fortune.

Hidden costs from the trade in national security

While the US and other governments have left the national security industry to grow and operate without proper regulation, the risks of conflict being exploited for monetary gain are growing all the time.

Hidden Costs documents how the former CEO of one major US private military and security company was convicted – following a guilty plea – of bribing Nigerian officials for a US$6bn land grab in the long-plundered Niger Delta.

Our research also highlights that the Saudi operatives responsible for Jamal Khashoggi’s savage murder received combat training from the US security company Tier One Group.

Arguably most damning are the accounts from Haiti, where the country’s president was killed last year by a squad of mercenaries thought to have been trained in the US and Colombia.

Pressing priority

Many governments around the world argue that critical security capability gaps are being filled quickly and with relatively minimal costs through the growing practise of outsourcing.

Spurred on by the US government’s normalisation of the trade, US firms are growing both their services and the number of fragile countries in which they operate.

The private military and security sector has swelled to be worth US$224 billion. That figure is expected to double by 2030.

The value of US services exported is predicted to grow to more than $80 billion in the near future, but the industry and the challenge faced is global.

The risks of corruption and conflict in the pursuit of profits are plain.

These risks are as old as time. But their modern manifestations in warzones must not be left to spill over. The 20-year war in Afghanistan cultivated dynamics that threaten further damage, more than a decade after governments first expressed their concerns.

Required response

International rules and robust regulation are urgently needed. We need measures that ensure mandatory reporting of private military and security company activities. The Montreux Document lacks teeth, operating as it does as guidance that is not legally binding. Code of conduct standards must also become mandatory for accreditation, rather than purely voluntary.

Most private military and security firms are registered in the US. So Transparency International Defence and Security is also calling on Congress to take a leading role in pushing through meaningful reforms under its jurisdiction. There is an opportunity arriving in September, when draft legislation faces review.

Policymakers have long been aware of the corruption risks and the related threats to peace and prosperity posed by this sector. The time for action is well overdue. No more Hidden Costs.

By Julien Joly, Thematic Manager, Corruption, Conflict and Crisis, Transparency International Defence & Security

Corruption, conflict and instability are profoundly intertwined. It has been shown time and again that corruption not only follows conflict but is also frequently one of its root causes.

Broadly speaking, corruption fuels conflict in two ways:

- By diminishing the effectiveness of national institutions; and

- By generating popular grievances.

Both of these elements contribute to undermining the legitimacy of the state, and in conflict this can empower armed groups who present themselves as the only viable alternative to corrupt governments. In turn this further contributes to the erosion of the rule of law, thus fuelling a vicious cycle.

Despite this, relatively little attention has been given to addressing corruption through peacebuilding efforts. As corruption is increasingly recognised for its role in fuelling conflict and insecurity around the world, it is imperative that initiatives seeking to address the root causes of violence and build lasting peace take this into consideration.

As a key element of the post-conflict peacebuilding agenda, Security Sector Reform (SSR) lends itself ideally to address the nexus between corruption and conflict. Applying the principles of good governance to the security sector to ensure that security forces are accountable offers legitimate avenues to mitigate corruption.

Nonetheless, evidence shows that strategies to mitigate corruption often fail to receive sufficient attention when it comes to designing and implementing SSR programmes. Such programmes overwhelmingly target tactical and operational reforms, designed for instance to train security forces or provide them with weapons and equipment, at the expense of structural reforms which would focus on bolstering accountability and reducing corruption. Similarly, in SSR policy frameworks developed by international and regional organisations, corruption is too often mentioned superficially and largely marginalised in favour of the ‘train-and-equip’ approaches described above. However, since the emergence of the concept of Security Sector Reform (SSR) in the 90s, there has been a shift from state-centric notions of security to a greater emphasis on human security. In this paradigm, based on the security of the individual, their protection and their empowerment, traditional ‘train-and-equip’ approaches to SSR have shown their limits.

It is clear that transparency, accountability, and anti-corruption are vital to ensure that security sector governance is effective. This means developing new approaches to SSR that, among other things, address corruption effectively.

In many areas, the anti-corruption community and the peacebuilding community would benefit from each other’s expertise. Reforming human resources management and financial systems, strengthening audit and control mechanisms, supporting civilian democratic oversight: these are areas where anti-corruption practitioners have been developing significant expertise over the past decades. They also happen to be key components of SSR.

But drawing from this expertise is only the beginning. In order to promote sustainable peace and contribute to transformative change in security sector governance, SSR needs to take a corruption-sensitive approach and address corruption as a cross-cutting issue. This requires implementing anti-corruption measures as a thread running through all SSR-related legislation, policies and programmes. In other words, this requires ‘mainstreaming anti-corruption in SSR’, which involves making anti-corruption efforts an integral dimension of the design, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of SSR policies and programmes.

While strengthening accountability and effectiveness in the security sector, anti-corruption provisions in SSR can be crucial in addressing some of the drivers and enablers of conflicts. Moreover, by upholding high standards of accountability, probity and integrity within the defence and security forces, anti-corruption fosters the protection against human rights abuses and violations. Ultimately, mainstreaming anti-corruption into SSR can harness its capacity to create political, social, economic and military systems conducive to the respect for human rights and dignity, ultimately contributing to long-lasting human security.

This blog is based on The Missing Element: addressing corruption through SSR in West Africa, a new report by Transparency International Defence and Security, available here.

La corruption dans le secteur de la sécurité a un impact néfaste à la fois sur le secteur de la sécurité lui-même et sur la paix et la sécurité au sens plus large, en alimentant conflits et instabilité. Des études quantitatives ont mis en évidence la correlation entre corruption et instabilité étatique. Les états dominés par des systèmes fondés sur le clientélisme sont plus susceptibles de souffrir d’instabilité. Il est peu surprenant que 6 des 10 pays ayant obtenu le score le plus bas dans l’Indice de perception de la corruption 2019 se trouvent également parmi les 10 pays les moins pacifiques dans l’Indice mondial de la paix 2020. La corruption nuit à l’efficacité des forces de sécurité et porte atteinte à la perception qu’ont les populations de la légitimité des autorités centrales.

En retour, cela alimente un sentiment de désillusion, menaçant ainsi le contrat social et, en fin de compte, l’état de droit. Dans certaines situations, la corruption peut également faciliter l’expansion des groupes extrémistes et non-étatiques et est devenue l’un des piliers des discours de recrutement. En dénonçant la corruption de l’Etat, ces mêmes groupes se présentent comme une alternative légitime aux gouvernements et aux élites corrompus.

Associée à des éléments tels que la pauvreté, les violations des droits de l’homme, la marginalisation ethnique et la proliferation des armes de petit calibre, la corruption du secteur de la sécurité a eu un effet alarmant sur la sécurité humaine en Afrique de l’Ouest. Au cours des trois dernières décennies, la corruption a appuyé certains des pires épisodes de violence dont la region a été témoin. Des guerres civiles au Liberia et en Sierra Leone au conflit actuel au Nigeria, où la corruption endémique a affaibli les forces de défense et de sécurité, alimenté la rancoeur à l’encontre des représentants des États et permis aux acteurs armés non-étatiques de combler le vide, la corruption a été un dénominateur commun de la plupart des conflits dans la région.

Pendant des décennies, la stabilité en Afrique de l’Ouest a été grandement perturbée par les conflits internes, souvent financés par la vente illégale d’armes ou l’extraction illicite de ressources naturelles. Que ce soit au Liberia, en Sierra Leone et en Côte d’Ivoire ou au Mali, au Burkina Faso et au Nigeria, la corruption a souvent conforté ces conflits et est à l’origine de mécontentements à l’égard des dirigeants politiques ainsi que de changements politiques violents.

En ébranlant la confiance du public et en nuisant à l’efficacité des institutions de défense et de sécurité, la corruption a porté atteinte à l’état de droit et a engendré une instabilité prolongée. Concrètement, cela a résulté pour de nombreuses personnes en une dégradation de l’accès aux services de base et a contribué à la création d’environnements propices aux violations des droits de l’homme.

Ce rapport soutient que, étant donné la grande menace que la corruption représente pour la paix et la stabilité en Afrique de l’Ouest, une attention accrue doit être portée aux travaux visant à lutter contre la corruption dans le cadre de la G/RSS. Il analyse le lien entre la corruption et les conflits en Afrique de l’Ouest par rapport à la prévalence des efforts visant à lutter contre la corruption dans les cadres de travail normatifs de la RSS, couramment utilisés en Afrique de l’Ouest, ainsi que dans un échantillon de pays entreprenant une G/RSS.

Par le biais de ce cadre de travail, notre recherche révèle le délaissement des efforts de lutte contre la corruption au profit d’approches de « formation et d’équipement » plus techniques. En conséquence, les structures de gouvernance sous-jacentes restent non affectées et les réseaux de corruption intacts, ce qui représente une occasion manquée d’exploiter les capacités de la G/RSS afin d’entraîner un changement transformateur.

This policy brief explains how corruption in the security sector has a detrimental impact both on the security apparatus itself and on wider peace and security, by fuelling tensions and adding to conflict and instability.

Quantitative studies have underscored how corruption and state instability are correlated, with states dominated by narrow patronage-based systems more susceptible to instability. It is little surprise that six out of the 10 lowest-scoring countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 are also among the 10 least peaceful countries in the Global Peace Index 2020. Corruption undermines the efficiency of security forces, damages populations’ conception of the legitimacy of central authorities and feeds a sense of disillusionment, which threatens the social contract, and ultimately the rule of law. In some situations, corruption can also facilitate the expansion of non-state and extremist groups and has become one of the lynchpins of recruitment narratives, which position these groups as a legitimate alternative to corrupt governments and elites.

Intersecting with factors that includes poverty, human rights violations, ethnic marginalisation and proliferation of small arms, security sector corruption has had an alarmingly negative effect on human security in West Africa. For the past three decades, corruption has underpinned some of the worst episodes of violence the region has witnessed. From civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone to the ongoing conflict in Nigeria, where rampant corruption has weakened defence and security forces, fuelled resentment against states’ representatives and enabled non-state armed actors to fill the vacuum, corruption has been a common denominator of most conflicts in the region.

February 25, 2021 – Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts in West Africa are being undermined by a failure to address underlying corruption and a lack of accountability in the region’s security sectors, according to new research by Transparency International.

The Missing Element finds that strengthening accountability and governance of groups including the armed forces, law enforcement and intelligence services – not just providing training and new equipment – is a crucial but often neglected component to successful security sector reform (SSR).

By analysing examples from across West Africa, the report details how the high threat of corruption has undermined the rule of law, fuelled instability, and ultimately resulted in SSR efforts falling short of their objectives.

The report serves as a framework for policymakers to assess how corruption is fuelling conflict, then embed anti-corruption measures to reform the security sector into one which is more effective at maintaining peace and more accountable to the population it serves.

Natalie Hogg, Director of Transparency International’s Defence & Security Programme, said:

“Stabilisation and peacebuilding efforts across West Africa have focussed largely on providing training and equipment but rarely resulted in major change. This report details how a focus on anti-corruption and strengthening accountability has been the missing element. Only by recognising and understanding the impact of corruption in the defence and security sector and taking steps to combat it can these programmes hope to transform the sector into one which is both efficient and accountable.”

The Missing Element analyses security sector reform and governance in five countries that our research has previously flagged as being at a high risk of defence sector corruption: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria.

It concludes these interventions fell short because the focus was on providing practical support such as training programmes and new weapons and equipment (with between 80-90% of funding for SSR initiatives typically spent on these) rather than addressing underlying corruption.

The report assesses the main corruption risks in West Africa which are undermining SSR efforts, including:

Financial management

Limited or ineffective supervision over how defence budgets are spent present a huge corruption risk, but reforms to improve transparency in this area have often been neglected as part of SSR programmes.

National defence strategies in Niger and Nigeria are so shrouded in secrecy that it is impossible to determine whether defence purchases are legitimate attempts to meet strategic needs or individuals embezzling public funds. In Mali, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire, a lack of formal processes for controlling spending has resulted in numerous examples of unplanned and opportunistic purchases.

Defence sector oversight

Effective oversight and scrutiny of the defence sector by parliamentarians is essential to increase accountability and reduce opportunities for corruption, but despite being a key pillar of SSR, parliamentary oversight remains poor in West Africa.

In Ghana, only a handful of the 18 members of the Parliament Select Committee on Defence and Interior have the relevant technical expertise to perform their responsibilities. In Mali, the parliamentary body charged with scrutinising the defence sector was chaired by the president’s son until mid-2020. In Niger, the National Audit Office, which is responsible for auditing the defence sector’s spending, published its audit for 2014 in 2017.

Recommendations:

- SSR policymakers at institutional level, such as United Nations (UN), African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), to publicly acknowledge the nexus between corruption and conflict, and adapt SSR policy frameworks accordingly.

- SSR practitioners operating in West Africa to undertake corruption-responsive SSR assessments to better inform the design of national SSR strategies and in all phases of their implementation.

- SSR practitioners to build on anti-corruption expertise to ensure that corruption is addressed as an underlying cause of conflict.

Notes to editors:

Security sector refers to the institutions and personnel responsible for the management, provision and oversight of security in a country. Broadly, the security sector includes defence, law enforcement, corrections, intelligence services and institutions responsible for border management, customs and civil emergencies.

Security sector reform (SSR) is a process of assessment, review and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation led by national authorities that has as its goal the enhancement of effective and accountable security for the state and its peoples without discrimination and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law.

The five countries analysed in this report (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria) were previously assessed in Transparency International Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index.

About Transparency International Defence & Security

The Defence & Security Programme is part of the global Transparency International movement and works towards a world where governments, the armed forces, and arms transfers are transparent, accountable, and free from corruption.