Show Index: gdi

This article originally appeared on the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) website.

By Ara Marcen Naval and Karolina MacLachlan.

Throughout the coronavirus outbreak, all eyes have been on the sector providing the frontline response to the epidemic: healthcare. But as the military steps in to assist in a growing number of countries around the world, there are questions about whether that could lead to additional problems.

The military capacity for rapid, large-scale movements – whether to protect hospitals, distribute supplies or increase transport capabilities – can be essential in responding to an infectious disease outbreak. Large-scale military deployments are likely to have the biggest impact in countries with weak healthcare systems and governance, limited civilian response capacities, vastly dispersed populations, or ongoing conflict and insecurity.

As low-income countries brace for the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and health authorities warn of challenges ahead, it is important to remember that large-scale military operations in support of the response to coronavirus in fragile and conflict states carry significant risks. Political, financial and health crises often expose cracks in the system that are less noticeable in more settled times. For instance, long-term governance gaps and ongoing corruption in armed forces can undermine civilian trust, making their work during crises more difficult. Military deployments during the Ebola outbreaks in the DRC and Liberia in 2014 and 2019 are examples of the role armed forces can play in limiting the scale of an epidemic – yet groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières also argued that years of abuse at the hands of the DRC’s military had made the local population wary of these troops, undermining their efforts.

Transparency International’s Defence and Security research shows that in many developing and fragile states, defence sectors tend to be poorly governed. High levels of secrecy and dysfunctional oversight structures often enable fraud, corruption and a wide range of abuses. The coronavirus crisis, like others before, has the potential to exacerbate these vulnerabilities, weakening militaries when they are needed most.

For example, where frontline soldiers go unpaid or have their salaries stolen by senior officers – a problem which research indicates affects the DRC, Iraq, Mali and Nigeria – militaries could see ill-disciplined units prone to avoiding service, busy trying to secure other sources of income or abusing civilians. A health and humanitarian emergency, which puts frontline responders at additional risk, could prove too much for those troops to handle, while sudden access to scarce resources could provide opportunities at the expense of the civilian population. Where militaries are already affected by corrupt practices, acceptance of small bribes and other favours can undermine containment efforts. Simultaneously, favouritism or corrupt networks could skew distribution of healthcare equipment by influencing the choice of priorities. Disciplinary issues, usually more widespread in states with weaker overall defence governance, could make an appearance or be exacerbated by the crisis. In the Philippines, for instance, President Duterte has already given police and military officials the order to shoot ‘troublemakers’.

Finally, a health and humanitarian crisis could see deployments of foreign troops into fragile and conflict states. As the Ebola example suggests, sizable deployments of US and UK forces into Liberia and the DRC helped construct and protect health facilities, distribute supplies and train healthcare workers. However, as international forces intervene in crises, the tangible and intangible resources they bring – such as cash, necessary items and political support for local actors – could further strengthen corrupt networks, as has been seen in countries such as Afghanistan. As Transparency International’s guidance on military interventions indicates, international forces themselves are also not immune to corruption, exacerbating challenges already in existence.

As economies weakened by coronavirus will require additional investment to rebuild, countries cannot allow uncontrolled resource outflows through defence and security institutions. Governments should take measures to strengthen defence governance immediately, offering a maximum level of protection in the short term and strengthening the global response. The authors recommend, for instance:

Inserting anti-corruption measures and the highest levels of transparency at the core of any new legislation (including that governing the distribution of resources) to respond to the emergency. This should include making publicly accessible contracts that govern financial flows and procurement associated with the crisis.

Ensuring that military deployments to help manage the emergency have clear timelines, independent oversight and are subject to review and audit mechanisms.

Extending protection to whistleblowers to help ensure that those who see corruption, whether in healthcare or in defence, can safely report it.

In the longer term and as the crisis recedes, it is key that attention to oversight and control of the defence sector becomes a priority, especially in fragile and conflict-affected states. Defence, healthcare and development are not mutually exclusive; slippage in one is likely to endanger progress in the other. Without fixing defence, sustainable development and better healthcare are unlikely to take root, especially in the most vulnerable countries.

Ara Marcen Naval is the Head of Advocacy for Transparency International – Defence & Security.

Karolina MacLachlan is Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Regional Programme Manager for Europe.

By Matthew Steadman, Project Officer – Conflict & Insecurity

2019 was a deeply concerning year for the Sahel. Attacks by extremist groups have increased five-fold in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso since 2016, with the UN now describing the violence as “unprecedented”. The past year was the deadliest by far with more than 4,000 deaths reported. Niger lost 89 soldiers in a single attack by Islamic State in Changodar in January, whilst two ISGS attacks in Mali in November claimed the lives of 92 soldiers. In Burkina Faso alone, 1,800 people were killed in the past year due to extremist violence. The intensification of extremist activity in the Sahel threatens to engulf West African coastal states, as already weakened national defence and security forces come under increasing pressure. Much international coverage of the developing events has focussed on the operational aspect of the crisis, from the various armed groups operating in the region to the international response, spearheaded by France’s Operation BARKHANE but also including MINUSMA, the G5 Sahel, the United States and the EU. However, one aspect that has been regularly overlooked is the poor capacity of the region’s national defence forces to respond to security threats as a result of poor defence governance, corruption and weak institutions.

Corruption and conflict go hand in hand, with corruption often fuelling violence and subsequently flourishing in afflicted regions. Because of corruption and poor governance, defence and security actors are often seen not as legitimate providers of security, but as net contributors to the dynamics of conflict; with poor training, management and institutional support leading to a downward cycle in which it is the civilians that more than often feel the brunt – as has been seen in Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Mali. When security institutions are perceived as corrupt, public confidence in government erodes further. Fragile governments that are unable to respond to the needs of citizens can exacerbate existing grievances, heightening social tensions and hastening the onset of violence. Across the Sahel, armed groups have been able to entrench themselves first and foremost in those areas which have been neglected by weakened and corrupt central authorities, often by positioning themselves as providers of security, justice and basic services. In this way, it is crucial to view corruption not just as the consequence of conflict, but more often as its root cause and therefore a critical element for any attempt at resolution to address.

Against this backdrop, research by Transparency International – Defence & Security’s Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI), highlights the deficiencies in the safeguards which should provide protection against corruption in the defence sectors of Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, increasing the likelihood of defence funds and capabilities being wasted due to mismanagement of human, material and financial resources. In doing so, the GDI outlines a number of key issues which need to be addressed in order to enhance security forces’ ability to respond to threats and protect local communities:

Reinforce parliamentary oversight

Despite most countries having formal independent oversight mechanisms for defence activities, policies and procurement, our research has found that these are often only partially implemented, easily circumvented and insufficiently resourced to carry out their mandates. The result, is defence sectors which are still largely the preserve of the ruling elite and shrouded in secrecy, raising concerns over the use of vital defence funds and the management of resources and assets.

Strengthen anti-corruption measures in personnel management and military operations

Personnel management systems are also vulnerable, with inadequate or non-existent whistleblowing protections and reporting mechanisms, unclear appointment, and promotion systems open to nepotism, and codes of conduct which fail to specifically mention corruption or enforce appropriate sanctions. Equally, despite many countries in the region being actively engaged in on-going counter insurgencies, there is no evidence of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso or Nigeria having up to date doctrine which recognises corruption as a strategic threat to operations, meaning there is little if any appropriate training on the pitfalls associated with operating in corrupt environments and little appreciation of how soldiers’ conduct might exacerbate the violence they are trying to quell.

Increase transparency and external oversight of procurement processes

Perhaps most concerning of all is that corruption risks in defence procurement remain extremely high across the region. The procurement process is opaque and largely exempt from the checks and balances which regulate other areas of public procurement in countries like Mali and Niger for instance. Across the region, the effectiveness of audit and control mechanisms over the acquisition of military goods and services is heavily restricted by blanket secrecy clauses and over-classification of defence expenditure. This raises serious concerns over the utility, relevance and value for money of purchased equipment and increases the risk of that frontline troops will not have the resources required to deliver security.

Despite these structural vulnerabilities, international assistance in the region has been heavily focussed on security assistance rather than on improving the underlying structures that govern and manage defence and security in the states that make up the region. The 13th January summit between French President Emmanuel Macron and the leaders of the G5 Sahel countries, was emblematic of this with the meeting focussed on reaffirming France’s military presence in the region and announcing the deployment of further troops, whilst side-lining the governance deficit which underlies so much of the crisis. Programmes have tended to focus on training and equipping military and police forces in Mali and Burkina Faso for instance, or improving strike capabilities by investing in US drone bases in Niger. The concern however, is that the impact of these efforts will be blunted without a more sustained engagement in addressing the more fundamental failings that lay at the hearty of the problem. Mali’s recent announcement of a recruitment drive for 10,000 new defence and security forces personnel for example, will only be effective if it is accompanied with improvements in the way these troops are trained, led, equipped and managed and if the political and financial processes which govern them are strengthened and corruption risks reduced.

A successful response, at the national, regional and international levels, to the violence cannot be just security focussed. Poor defence governance and corruption risks will continue to hamper national forces’ operations and will hinder the impact of international efforts which support them. A more comprehensive approach is needed which addresses the underlying corruption risks which permeate the region’s defence sectors. Improving oversight, transparency and accountability is a critical step in securing a sustainable peace in the region and ensuring that defence and security apparatuses do what they should, which is to further the human security of populations that they should be serving.

January 14, 2020 – Sweeping reforms to controls on American arms sales abroad are increasing holes in checks to identify and curb corruption – measures that can also be used to assess whether sales may help or hurt efforts to address terrorist threats and attacks – according to new research by Transparency International Defense & Security.

Launched today, Holes in the Net assesses the current state of US arms export controls by examining corruption risk in three of the most prominent sales programs, which together authorized at least $125 billion in arms sales worldwide for fiscal year 2018.

Across all three different arms sales programs, which are managed by the Defense, State, and Commerce Departments, there is a clear gap in American efforts to assess critical, known corruption risk factors. This include the risks of corrupt practices – such as theft of defense resources, bribery, and promoting military leaders based on loyalty instead of merit – weakening partner military forces.

The United States is one of the biggest arms exporters to countries identified as facing ‘critical’ corruption risk in their defense sector, including Egypt, Jordan, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, according to recent analysis by Transparency International – Defense & Security.

Steve Francis OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defense & Security, said:

“Given the corrosive effect corruption has on military effectiveness and legitimacy, it is deeply concerning to see that these reforms to American arms export controls have made it easier for practices like bribery and embezzlement to thrive. In order to ensure American arms sales do not fuel corruption in countries like Egypt, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, it is imperative to understand and mitigate the corruption risks associated with countries receiving US-made weapons before approving major arms deals.”

Of the three programs assessed in the report – Foreign Military Sale, Direct Commercial Sale, and the 600 Series – the 600 Series was identified as having the biggest gaps in its anti-corruption measures. Overseen by the Commerce Department, sales through this program do not require declarations on a series of major corruption risk areas, including on certain arms agents or brokers, political contributions, company subsidiaries and affiliates, and any defense offsets. These areas are common conduits used for bribery and political patronage.

More recently, the Trump administration has proposed moving many types of semi-automatic firearms and sniper rifles to Commerce Department oversight. The proposal calls for additional controls for firearms, but also reduces overall oversight of small and light weapons exports.

Colby Goodman, Transparency International – Defense & Security consultant and author of the report, said:

“Over the past 30 years, America has established some of the strongest laws to prevent bribery and fraud by defense companies engaged in arms sales. However, defense companies selling arms through the 600 Series program no longer have to comply with key anti-corruption requirements. As a result, US officials will likely find it harder to identify and curb bribery and fraud in sales of arms overseen by the Commerce Department.”

The report analyzed five priority corruption risk factors for American arms sales programs: 1) Ill-defined and unlikely military justification; 2) Undisclosed or unfair promotions and salaries in recipient countries; 3) Under-scrutinized and illegitimate agents, brokers and consultants; 4) Ill-monitored and under-publicized defense offset contracts, and 5) Undisclosed, mismatched or secretive payments.

The report makes a series of policy recommendations that would help strengthen anti-corruption measures in these prominent arms sale programs, including:

- Creating a corruption risk framework for assessing arms sales through programs managed by the Defense, State, and Commerce Departments. These assessment frameworks must examine key risk factors identified in our report, including theft of defense resources and promoting military leaders based on loyalty instead of merits, among others.

- Strengthening defense company declarations and compliance systems for sales of arms overseen by the Commerce Department, including declarations of any defense company political contributions, marketing fees, commissions, defense offsets, and financiers and insurance brokers of arms – all clear conduits for corruption.

- Increasing transparency on arms sales and actions to combat arms trafficking overseen by the Defense, State, and Commerce Department. Critically, the Defense and State Departments need more details on defense offsets in order to properly review proposed arms sales. There is virtually no information on Commerce Department approved arms sales.

- Legislation requiring for firearms and associated munitions to remain categorized as munitions to ensure further relaxing of export controls do not adversely impact US national security or foreign policy objectives.

Notes to editors:

Interviews are available with the report author.

Holes in the Net is available to download here.

Saudi Arabia, a major importer of US-made arms, failed to defend against an attack on its oil facilities in September 2019. Reports have suggested that corrupt ‘coup-proofing’ measures designed to shield the ruling family likely contributed to the ineffective response.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

+44 (0)79 6456 0340

Corruption is widely recognized as one the major stumbling blocks in US government efforts to improve the capacity of foreign defense forces to address shared international security threats over the past 15 years.

This report assesses the current state of US arms export controls to identify and curb corruption in US arms sales. It first highlights critical corruption risk factors the United States should consider in order to help prevent corruption and fraud in its arms sales. The report then assesses US laws, policies, and regulations aimed at identifying and mitigating corruption and fraud risks in US arms sales.

Defence industry players, elected officials, the defence bureaucracy, and governments in the Middle East are intertwined and serve one another’s interest, often at the expense of US foreign policy outcomes. These mutually-beneficial relationships have contributed to a vicious cycle of conflict and human rights abuses across the Middle East and North Africa, including increased exports of arms and defence services to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates which began under the Obama administration and have ramped up under President Trump.

20th December, London – The complex web of murky pathways through which the American defense industry works to secure permission to export arms to repressive regimes in the Middle East has been laid bare in new research by Transparency International – Defence & Security.

A Mutual Extortion Racket: The Military Industrial Complex and US Foreign Policy reveals how defense industry players, elected officials, the defence bureaucracy, and governments in the Middle East – working through intermediaries such as lobbyists, think tanks, and public relations firms – are intertwined and serve one another’s interest, often at the expense of US foreign policy outcomes.

These mutually-beneficial relationships have contributed to a vicious cycle of conflict and human rights abuses across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including increased exports of arms and defence services to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates which began under the Obama administration and has ramped up under President Trump.

Steve Francis OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defense & Security said:

“In the midst of the unending war in Yemen and after the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi last year, questions have been asked over why American arms exports to places like Saudi Arabia and the UAE have not only continued, but accelerated. After examining the murky web of lobbying, campaign finance, revolving door employment, and sometimes even downright corruption, it is now clearer how these exports are allowed to continue, despite attempts by many in Congress to stem the flow.

“While much of the system that allows these exports to continue is riddled with a lack of transparency and oversight, there are some areas in which existing strengths can be amplified. We urge Congress and the Executive branch to adopt our recommendations and ensure that arms exports are better aligned with US foreign policy interests and the American defense industry no longer wields excessive influence over policymaking.”

The pathways which allow this ‘extortion racket’ to play out include:

- Controversial sweeteners bolted on to defence contracts known as ‘offsets’

Despite rarely making economic sense, these side deals account for US$3 to $7 billion in obligations every year – and the lack of transparency around offsets means they are a notorious conduit for corruption. A series of leaked emails in 2017 revealed that American defence firms were indirectly funding advocacy campaigns around drones which were friendly to the Saudi and Emirati governments. Money from the US companies was paid directly into an Emirati development fund which was eventually routed to a US think tank who created the campaigns.

- Political campaign donations

‘Dark money’ groups such as the US Chamber of Commerce, the largest American business lobbying organization, are under no obligation to reveal their donors but can contribute to influence political campaigns, especially via so-called Super PACs. According to a defence lobbyist, the Chamber aims to move any discussion about US defense exports “straight down to dollars and jobs in a congressional district” to incentivise members of Congress not to take any steps that could impact arms sales.

- The so-called ‘revolving door’ between high-level jobs in government and the military and senior roles with defense companies or lobbying firms.

After leaving Congress, Republican Howard McKeon set up a lobbying firm which boasts its status as “the only firm led by a former Chairman of two full congressional Committees”. McKeon signed as a registered foreign agent for the Saudi government in 2016 soon after setting up his firm. During his tenure as Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, $10 billion in military sales were approved to Saudi Arabia – a doubling of previous sales to the country.

Rarely is just one of the pathways identified in the report is used and they are often intertwined to magnify influence towards desired policy outcomes.

Simply limiting lobbying and campaign finance contributions is necessary but not enough to rebalance the egregious flaws of this influence system. Our policy recommendations include:

- Establish a ‘Defense Exports Czar’ on the National Security Council to oversee all aspects of security assistance, including defence exports, and assess whether exports align with larger US foreign policy goals.

- Legislate a ban on offset contracts between the American defence industry and foreign governments.

- Re-establish the State Department as the lead agency for all security assistance, including all defense exports, while Congress should demand more insight and transparency into these exports

- Require all contractors and sub-contractors to list their beneficial owners to ensure contract funds are not funnelled to those tied to corrupt politicians, insurgents, terrorists, warlords or criminal actors.

- Establish legislation to limit contributions to super PACs by the defense industry or its intermediaries and prevent anonymous donations; require defence firms to publicly disclose all donations or political activity over $10,000.

Notes to Editors:

The report is available to download here.

Transparency International’s newly-released Government Defence Integrity Index scores countries according to the risk of corruption in their defence institutions. Saudi Arabia was ranked F – indicating a critical risk – while the UAE was ranked E, indicating a very high risk.

The American arms industry is the largest in the world. In 2018, American companies were responsible for 57 percent of worldwide arms sales, totalling $226.6 billion.

The sector is also a major force in US manufacturing in employment. In 2017, 10 percent of the $2.22 trillion factory output went to produce weapons sold to the Defence department.

Between 2012 and 2015, the US exported 46 percent of all arms delivered to the Middle East. In 2016, 35 of the 57 arms sales proposed were to countries in the MENA region.

Contact:

Interviews are available with the report author.

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

++44 (0)79 6456 0340

By Steve Francis OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security

The Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) is the first global analysis of corruption risks and the existence and enforcement of controls to manage that vulnerability in defence and security institutions, highlighting priority areas for improvement. Key to analysing results from the Index is understanding that the GDI measures corruption risk, not levels of corruption per se.

GDI data will be released in regional waves through 2020. Results from the most recent wave – the Middle East and North Africa – were published in November.

On the whole, the data paints a fairly bleak picture for the region. Tunisia leads the group with an overall grade of “D,” indicating a “high” degree of defence corruption risk, while the other 11 assessed countries received either an “E” or an “F” – signalling “very high” or “critical” levels of risk. Regional averages reflect a similar performance across the individual risk areas – political, financial, personnel, operations, and procurement.

With these findings in mind, what can the analysis of the GDI’s result teach us about protracted cases of armed conflict, political instability, and insecurity that seem to characterise the region?

1. In many cases, high defence corruption risk is symptomatic of wider governance issues.

The GDI’s political risk indicators and aggregated scores on anti-corruption themes examine broader issues of legislative oversight, public debate, access to budgetary information, and civil society activity – issues that don’t just impact the defence sector. Indeed, this area of the assessment highlights essential ingredients for any open and transparent government that engages constructively with its citizens. As most of the assessed MENA countries are governed by authoritarian regimes, we should not be too surprised then that these wider governance challenges also exist in the defence sector. Specifically, our data found a clear lack of external oversight, audit mechanisms, and scrutiny of defence institutions across the region.

Table: MENA region average scores for key political risk indicators and anti-corruption themes

| Question | Indicator/Theme | Score | Grade |

| Q1 | Legislative scrutiny of defence laws and policies | 15 | F |

| Q3 | Defence policy debate | 9 | F |

| Q4 | CSO engagement with defence and security institutions | 15 | F |

| Q6 | Public debate of defence issues | 23 | E |

| Q13 | Defence budget scrutiny | 10 | F |

| Q17 | External Audit | 8 | F |

| Aggregate | Openness to civilian oversight | 14 | F |

| Aggregate | Oversight | 14 | F |

| Aggregate | Budgets | 15 | F |

| Aggregate | Transparency | 15 | F |

| Aggregate | Undue influence | 19 | E |

2. Countries with the highest defence corruption risk are also significant arms importers.

Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Algeria were three of the world’s top five arms importers from 2014-2018. All three received an “F” grade in the GDI, with Egypt and Algeria receiving the bottom two regional scores (6/100 and 8/100, respectively).

The region has gaps in export controls, with only Lebanon and Palestine having ratified the Arms Trade Treaty, in addition to related risks like a lack of regulation around lobbying in defence and virtually no transparency around defence spending.

Although major arms exporters to the region like the United States have rules against the transfer of arms to third parties, end-use monitoring is not always consistent or comprehensive. This is especially troubling given that top arms importers in the region are either directly involved in or are arming parties to the devastating conflicts in both Yemen and Libya.

3. Low-scoring countries also exhibit high corruption risk by blurring the line between business and defence.

While the region as a whole scored poorly on indicators relating to the beneficial ownership (47/100) and scrutiny of military-owned businesses (44/100), these risks are greatest in countries with extensive military-run industries and/or significant natural resources. In Egypt for example, the military owns lucrative businesses across industries ranging from food and agriculture to mining, but has few controls in place for regulating these ventures. In Algeria, a largely state-owned economy renowned for high levels of corruption and patronage, there are a range of potential implications now that the military has stepped in to fill the vacuum following the ousting of President Bouteflika in March 2019 following mass public unrest.

The Gulf monarchies offer an example of how defence and business can overlap at the level of the individual. In the assessment for Saudi Arabia, we found that members of the royal family who serve in senior military positions also have controlling or financial interests in businesses related to the country’s petroleum sector. In the UAE as well, our research found that Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, is also the Chairman of a company dealing in natural resources.

On the other end of the spectrum, the GDI found that in Morocco, Palestine, and Tunisia, defence and security institutions do not own businesses of any significant scale, thereby removing a significant source of corruption risk.

As the GDI data shows, the risk of defence corruption in the MENA region is a serious concern with the potential to exacerbate ongoing conflict and instability. However, robust tools like the GDI can help governments to identify gaps in safeguarding practices – the first step in a process towards reform – while supporting civil society and oversight actors in countries across the region in conducting evidence-based advocacy.

6 December, Niamey – Security and stability in Niger are threatened by high levels of corruption risk in its national defence sector, according to new research by Transparency International – Defence & Security.

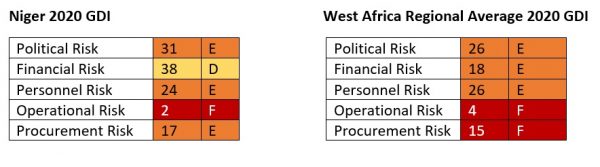

Niger’s defence sector scores poorly in the 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index, which is today being launched in Niamey. Receiving a majority of E and F grades, indicating either a “very high” or “critical” risk of defence corruption, the analysis assesses corruption risk across five key areas: political, financial, operations, personnel and procurement.

But Niger’s overall score of 22/100 places it above the regional average of 18/100, with levels of corruption risk in the country’s political, financial and procurement categories lower than in the region, but higher in terms of personnel and operations.

Steve Francis, OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

“In recent years, Niger has become increasingly affected by the conflict and insecurity in neighbouring Mali, which has quickly spread across the Sahel. With Niger now a key member of the G5 Sahel Joint Force, contributing over a thousand troops to the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali and receiving increasing amounts of military and technical assistance from foreign donors, the country is on the frontline of the regional struggle against extremist groups.

“Given the empirical link between corruption and conflict and the corrosive effect of corruption on defence capabilities, it is essential for Niger to accelerate its efforts to improve the governance of the defence sector and strengthen civilian democratic oversight of the defence apparatus. We urge the Nigerien government to improve the access to defence information of legislative and oversight bodies and take steps towards improving transparency and external oversight in procurement processes. Building the integrity and effectiveness of Niger’s defence sector will enhance its ability to respond to multiplying regional security threats and bolster public trust in defence and security institutions.

“With high corruption risks across national defence sectors in West Africa, tools like our Government Defence Integrity Index are more important than ever. By highlighting areas where safeguards against corruption are weak or non-existent, campaigners on the ground and reform minded military leaders and politicians can use these results to push for real change. Taking action to improve transparency and closing the loopholes which allow corruption to thrive is a critical step in building effective and accountable defence and security forces.”

These findings come against a backdrop of rising insecurity in Niger and the Sahel more broadly. Attacks by extremist groups against civilians and Nigerien defence and security forces are rising, while the protracted conflicts in Mali and Libya are increasingly spilling across the border into Niger. Mounting instability in Burkina Faso, Northern Nigeria and the Lake Chad region are also threatening to seriously impact the security of populations along Niger’s southern border and are turning the landlocked nation into a critical base in the fight against violent extremism.

Despite recent promising government initiatives and reforms, attempts to improve defence governance in Niger are hindered by high levels of secrecy and defence exceptionalism, which severely limit oversight and control of defence institutions by parliament and audit mechanisms.

The capacity of the National Assembly to hold the government to account is hampered by a lack of technical expertise and limited access to information, whilst a general lack of engagement between the defence establishment and civil society further limits the scope of civilian democratic oversight.

Financial oversight is also curtailed by the lack of a detailed defence budget made available to the legislature. Even the parliamentary Defence and Security Commission is presented with only abbreviated information when it comes to spending on secret items and military intelligence, whilst audit mechanisms are limited in terms of capacity and access to information. This lack of oversight is mirrored in Niger’s defence procurement process, with many purchases excluded from normal public procurement procedures. Moreover, reports from the Inspector General, along with the military acquisition plan are strictly confidential, thereby hugely hindering external control.

Personnel management would be improved through a greater emphasis on addressing corruption, for instance through revamped Codes of Conduct and specific anti-corruption training which are currently lacking. Equally, the nomination and recruitment processes at higher levels are shrouded in secrecy, opening the door for nepotistic practices.

Finally, Niger’s defence sector scores very poorly in terms of operational risk, with its military doctrine lacking an appreciation of corruption as a strategic threat during deployments.

At a time of growing regional instability, Transparency International – Defence & Security urges the Nigerien government to consider heightening efforts to improve civilian democratic oversight of the defence sector and strengthening the integrity of the armed forces to better respond to the security threats with which it is faced.

Notes to editors:

The full, country-specific Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) results for Niger and West Africa as a whole are available at https://ti-defence.org/gdi/

The GDI assesses the existence, effectiveness and enforcement of institutional and informal controls to manage the risk of corruption in defence and security institutions.

Our team of experts draws together evidence from a wide variety of sources and interviewees across 77 indicators to provide a detailed assessment of the integrity of national defence institutions, and awards a score for each country from A to F.

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI). The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. This means overall country scores from this 2020 version cannot be accurately compared with country scores from previous iterations of the Index.

Subsequent GDI results will be released in 2020, covering Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America, G-20 countries, the Asia Pacific region, East and Southern Africa, and NATO+.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

++44 (0)79 6456 0340

By Stephanie Trapnell, Head of Research, and Michael Ofori-Mensah PhD, Project Manager

How to govern military power presents one of the great global challenges of our age. Powerful, secretive and responsible for the world’s most destructive capabilities, when the governance of defence fails, it fails spectacularly, often leading to conflict and further instability. And yet many national defence sectors lack the basic governance standards of other public sectors. Reform programmes are difficult to steward through to success, but the rewards of doing so can improve military effectiveness and help reconnect armed forces with the societies they serve.

To aid this process, Transparency International has developed the evidence-based Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI). It is the first global analysis of corruption risks and the existence and enforcement of controls to manage that vulnerability in defence and security institutions, highlighting priority areas for improvement.

The 2020 iteration of the GDI focuses on 89 countries, selected based on the following criteria:

- their significant and/or high-profile roles in the global arms trade

- being at risk for political or defence-related instability

- undergoing reforms that were expected to result in changed circumstances for defence integrity.

As such, it has a crucial role to play in driving global defence reform. The GDI is designed to be a tool for governments seeking to improve their integrity protocols and a platform to share best practice with civil society, international organisations, the media and country investors, identifying where they need to push for change in the sector.

Overall, our experience to date shows that where governments have used the GDI as a roadmap for reforms, it can make a strong contribution to bringing about positive changes and mitigate the risks corrupt practices can pose to a state’s legitimacy and ability to respond to threats.

What does the GDI measure?

The GDI measures corruption risk, not levels of corruption per se. It assesses that risk in the entire defence and security sector within a country, which involves evaluating the factors that facilitate corruption, and the dynamics that produce an environment in which corruption can flourish unchecked. It is not concerned with measuring the amount of funds that are lost, identifying corrupt actors, or estimating the perceptions of corruption by the general public.

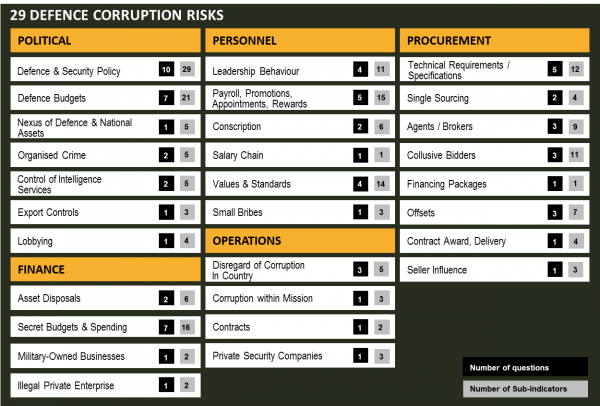

The index is organised into five key corruption risk areas: political, financial, personnel, operational, and procurement, which are further broken down into 29 specific defence corruption risks.

Our team of experts draws together evidence from a wide variety of sources and interviewees across 212 indicators to provide a detailed assessment of the integrity of national defence institutions, and awards a score for each country from A to F. In order to provide a broad and comprehensive reflection of these risk areas, the GDI assesses both legal frameworks (de jure) and implementation (de facto), as well as resources and outcomes. Scorecards, overviews, and profiles for each country can be found here.

What is the overall goal of the GDI?

Good practice standards. The GDI provides a framework of good practice that promotes accountable, transparent, and responsible governance in the defence establishment. This standard of good practice stems from our extensive work over the last decade in working towards more accountable defence sectors and highlighting the connection between corruption and instability.

Evidence-based advocacy. The GDI is a useful tool for civil society to collaborate with Ministries of Defence, and military and oversight institutions to build their capacity in transparency and integrity. It provides rigorous evidence-based data for those focusing on the nexus of corruption and defence.

Robust programmatic approaches. Transparency International – Defence & Security has extensive experience using the index to support reform efforts. This includes: drafting integrity action plans, supporting integrity training workshops, facilitating consultation processes with civil society, and building capacities of parliamentarians to exercise oversight.

Data for countries in West and Central Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa, have recently been released. Subsequent GDI results will be released in 2020, covering Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America, G-20 countries, the Asia Pacific region, East and Southern Africa, and NATO.

Note: The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI). The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. This means overall country scores from this 2020 version cannot be accurately compared with country scores from previous iterations of the Index. For more information on the GDI methodology, click here.

25 November, London – Security and stability across the Middle East and North Africa continues to be undermined by the risk of corruption in defence institutions, according to new research by Transparency International – Defence & Security.

11 of the 12 Middle East and North Africa states assessed in the 2020 Government Defence Integrity Index released today received E or F grades, indicating either a “very high” or “critical” risk of defence corruption. Only Tunisia performed better, scoring a D.

These findings come against a backdrop of insecurity and fragility in the region. Mass protests – driven by grievances including corruption and financial mismanagement by government – continue in Egypt, Iraq and Lebanon. Meanwhile protracted armed conflicts in Syria, Yemen and Libya show no sign of ending.

Steve Francis OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defence & Security, said:

The Middle East and North Africa remains one of the most conflict-riven regions in the world and this instability has a major impact on international security. While some states have made some improvements in their anti-corruption safeguards, the overall picture is one of stagnation and in some cases regression. Given the empirical link between corruption and insecurity, these results make worrying reading.

Military institutions across the region continue to conduct much of their business under a shroud of secrecy and away from even the most basic public scrutiny or legislative oversight. This lack of accountability fuels mistrust in security services and governments, which in turn feeds instability.

With the regional picture looking bleak, tools like our Government Defence Integrity Index are more important than ever. By highlighting areas where safeguards against corruption are weak or non-existent, campaigners on the ground and reform minded military leaders and politicians can use these results to push for real change. Taking action to improve transparency and close loopholes which allow corruption to thrive would improve public trust and bolster national security.

Defence sectors across the region continue to suffer from excessive secrecy, and a lack of oversight and transparency, the research found. Meanwhile, defence spending in the region continues to surge to record levels.

The countries with defence sectors at a ‘critical’ risk of corruption are Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, as there is virtually no accountability or transparency of defence and security institutions. Many of these countries are either major arms importers or benefit from significant international military aid.

In Lebanon, a lack of clear independent auditing mechanisms and gaps between anti-corruption laws adopted in the last two years and their implementation contributed to the country’s “very high” risk status, despite the Lebanese Armed Forces demonstrating high levels of integrity and a willingness to remain neutral and avoid using excessive against protesters.

Tunisia was the only country in the region to rank higher, with new whistleblower protections, improved oversight and public commitments to promoting integrity in the armed forces contributing to its score. But the continued use of counter-terrorism justifications combined with an ingrained culture of secrecy within the defence sector prevented Tunisia from scoring higher.

| Country | Risk banding |

| Tunisia | High risk |

| Lebanon | Very high risk |

| Palestine | |

| Kuwait | |

| UAE | |

| Algeria | Critical risk |

| Egypt | |

| Jordan | |

| Morocco | |

| Oman | |

| Qatar | |

| Saudi Arabia |

Notes to editors:

The full, country-specific Government Defence Integrity Index (GDI) results for the Middle East and North Africa will be available here

The GDI assesses the existence, effectiveness and enforcement of institutional and informal controls to manage the risk of corruption in defence and security institutions.

Our team of experts draws together evidence from a wide variety of sources and interviewees across 77 indicators to provide a detailed assessment of the integrity of national defence institutions, and awards a score for each country from A to F.

The GDI was previously known as the Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI). The Index underwent a major update for the 2020 version, including changes to the methodology and scoring underpinning the project. This means overall country scores from this 2020 version cannot be accurately compared with country scores from previous iterations of the Index.

Subsequent GDI results will be released in 2020, covering Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America, G-20 countries, the Asia Pacific region, East and Southern Africa, and NATO+.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

Harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

++44 (0)79 6456 0340

Mallary Gelb

mallary.gelb@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

++44 (0)79 6456 0340

Corruption is widely recognized as one of the fundamental drivers of conflict in Mali. A lack of accountability to the population and a failure to address internal patronage networks has fed into two coup d’états, human rights abuses and the permissive environment for transnational trafficking and organized criminal activity that has fuelled regional conflict. In the meantime, by reducing the operational effectiveness of the Malian armed forces, corruption undermines the state’s ability to field a defence and security apparatus that can guarantee the population protection from insurgent groups, armed violence, or the resurgence of civil war.

Whilst the lack of safety and insecurity linked to conflict is one of the top five most important problems reported by Malians across the country, weak governance in the defence and security sector has hugely corroded public confidence in the government and state security institutions.

This mistrust has been exacerbated by a high level of secrecy and a lack of transparency in the defence sector that have meant that the otherwise vibrant Malian civil society has been unable to provide robust oversight over defence policies, or play a role in combating defence corruption. Civil society in turn has limited capacity to oversee the sector’s activities and requires increased expertise on defence governance and accountability to develop well-evidenced and holistic reform recommendations. At the same time, it lacks opportunities to engage with officials at the level required to catalyze reforms within state institutions. This has given the Malian army the freedom to act largely unmonitored in the North and other insecure areas at a time when the country’s security and integrity is challenged on a daily basis.

Building on our expertise as well as on inputs from Malian civil society organisations from across the country, this report will provide best practice guidelines and recommendations which are designed to diminish the space for corruption and to improve the governance and institutional strength of Mali’s defence sector.

The French Translation of this report can be downloaded here.

October 24, Bamako – Mali’s defence sector has undergone a comprehensive health check in new research from Transparency International – Defence and Security (TI-DS), which stresses the need for urgent action to tackle corruption in order to enable the military to better respond to Mali’s numerous security threats.

Building Integrity in Mali’s Defence and Security Sector assesses the strength of institutional safeguards to corruption in the Malian defence sector and highlights weaknesses in key institutions which have created an environment in which corrupt practices have been able to thrive.

As part of TI-DS’ work to promote integrity in defence sectors across West Africa, this report is designed as an advocacy tool for Malian civil society organisations and campaign groups.

By highlighting the drivers and enablers of corruption and providing tailored recommendations and guidelines, TI-DS offers a roadmap to improved governance and a more accountable military.

Steve Francis OBE, Director of Transparency International – Defence and Security, said:

“Corruption and conflict go hand in hand and their coexistence feeds violence and insecurity. Nowhere is this vicious cycle more evident than in Mali where a lack of integrity and accountability has fuelled two coup d’états and weakened the security forces further.“

“In order to tackle the current security crisis, and to protect the population from future threats, the corruption undermining public trust in the military and reducing its operational effectiveness must be weeded out. We urge the Malian authorities to consider adopting and implementing these policy proposals to help reduce and even eliminate some of the primary enablers of corruption in the defence and security sector. The prize for doing so a military force that the people of Mali want and deserve.”

Key recommendations include:

· Greater oversight of defence purchases and finances. Mali’s defence institutions would benefit from greater oversight and controls over defence purchases and finances. This would enable the efficient use of precious resources and ensure that the Malian defence and security forces are provided with the right equipment to respond to the country’s security threats.

· Harness the powers of the National Assembly. Although the Malian Constitution provides the National Assembly with adequate powers to scrutinise the actions of the executive, it needs further means and the expertise to perform proper oversight over defence. Moreover, access to information remains limited as the overclassification of information curtails its capacities to monitor defence activities and scrutinise budgets.

· Strengthen the integrity of the sector. Mali’s defence establishment suffers from a lack of accountability and transparency in human resource and asset management which has negatively impacted the integrity of the defence apparatus. More transparent, objective and clearly defined human resource and asset management processes will help professionalise and improve the effectiveness and integrity of the armed forces.

This research comes at a crucial time for Mali. Since the near-collapse of the Malian military in 2012, government troops have been battling jihadist militants in the north of the country.

This continued insurgency has prompted local militias to take measures to protect their own interests, further complicating the security situation for the government and exacerbating the suffering of Mali’s citizens.

Note to Editors:

Building Integrity in Mali’s Defence and Security Sector is being officially launched today, October 24, in Bamako.

Contact:

Harvey Gavin

Harvey.gavin@transparency.org.uk

+44 (0)20 3096 7695

++44 (0)79 6456 0340

Transparency International is the civil society organisation leading the fight against corruption